| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Pennsylvania |

|---|

|

|

|

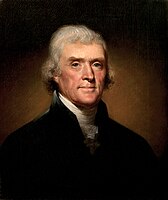

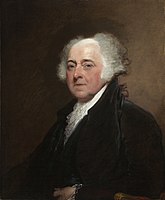

The 1800 United States presidential election in Pennsylvania took place on December 1, 1800, during a special session of the Pennsylvania General Assembly.[1] Members of the bicameral state legislature chose 15 electors to represent Pennsylvania in the Electoral College as part of the 1800 United States presidential election. Eight Democratic-Republican electors and seven Federalist electors were selected. Unlike in the previous election, when one elector split his ballot between Republican Thomas Jefferson and Federalist Thomas Pinckney, all 15 electors followed the party line, with the Republicans voting for Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr and the Federalists for incumbent President John Adams and his running, mate Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. This was the first and only U.S. presidential election in which Pennsylvania's electors were not chosen by popular vote.[2]

Nationally, Jefferson and his Burr, received 73 electoral votes apiece, to 65 for Adams and 64 for Pinckney. The tie between Jefferson and Burr led to a contingent election in the House of Representatives, which Jefferson won, becoming the third president of the United States on March 4, 1801.[2]

In 1800, there was no general statute governing all elections in Pennsylvania; instead, the legislature passed a new law in advance of each election to lay out the rules by which it would proceed. Following the 1799 state elections, the Assembly was divided between the Republican-controlled House of Representatives and the Federalist-controlled Senate and was therefore unable to pass an election law. House Republicans supported a plan to choose all 15 electors by a statewide popular vote, as had been done in previous elections, but the 13 Federalist senators opposed this measure in the belief Jefferson would win an overwhelming victory (as he had in 1796) if the choice were put to the population at-large. They instead proposed that the electors be chosen from specially-drawn districts in order to maximize the Federalist vote and deny Jefferson the whole part of the Pennsylvania delegation.[2][1]

The deadlock continued well into the fall of 1800, at which point a popular vote became impractical, and the debate turned to how the electors would be chosen by the Assembly itself. The Republicans favored selecting all 15 electors in a joint session of the entire Assembly, but the Federalists, who would have been outnumbered in that case, demanded separate elections in the Senate and the House. Outraged Republicans undertook a public campaign in support of a joint selection but failed to sway the holdout senators. Finally, under a compromise proposed by Governor Thomas McKean, seven Republican and seven Federalist electors were appointed, with the fifteenth elector to be chosen by a joint session of the Assembly. Believing incorrectly that South Carolina's electors would give the Federalist ticket a narrow majority in the Electoral College if Pennsylvania's votes were not recorded, Republican leaders agreed to the compromise. Samuel Wetheril, the Republican nominee, defeated Robert Coleman, the Federalist nominee, by a vote of 60 to 33 to become the final elector, giving the Republicans eight of Pennsylvania's 15 electoral votes to seven for the Federalists. Seven members of the Assembly did not vote and two had not yet taken the oath of office.[1][3]

- ^ a b c d "PENNSYLVANIA AND THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 1800: REPUBLICAN ACCEPTANCE OF THE 8-7 COMPROMISE". Penn State University. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c "1800 ELECTION FOR THE FOURTH TERM, 1801-1805". National Archives. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

resultswas invoked but never defined (see the help page).