| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 11 Alabama votes to the Electoral College | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

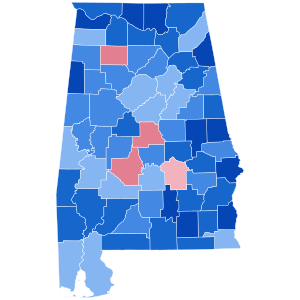

County results

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Alabama |

|---|

|

|

|

The 1952 United States presidential election in Alabama took place on November 4, 1952, as part of the 1952 United States presidential election. Alabama voters chose eleven[3] representatives, or electors, to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president. In Alabama, voters voted for electors individually instead of as a slate, as in the other states.

Since the 1890s, Alabama had been effectively a one-party state ruled by the Democratic Party. Disenfranchisement of almost all African-Americans and a large proportion of poor whites via poll taxes, literacy tests[4] and informal harassment had essentially eliminated opposition parties outside of Unionist Winston County and presidential campaigns in a few nearby northern hill counties. The only competitive statewide elections during this period were thus Democratic Party primaries — limited to white voters until the landmark court case of Smith v. Allwright, following which Alabama introduced the Boswell Amendment — ruled unconstitutional in Davis v. Schnell in 1949,[5] although substantial increases in black voter registration would not occur until after the late 1960s Voting Rights Act.

Unlike other Deep South states, soon after black disenfranchisement Alabama’s remaining white Republicans made rapid efforts to expel blacks from the state Republican Party,[6] and under Oscar D. Street, who ironically was appointed state party boss as part of the pro-Taft “black and tan” faction in 1912,[7] the state GOP would permanently turn “lily-white”, with the last black delegates at any Republican National Convention serving in 1920.[6] However, with two exceptions the Republicans were unable to gain from their hard lily-white policy. The first was when they exceeded forty percent in the 1920 House of Representatives races for the 4th, 7th and 10th congressional districts,[8] and the second was 1928 presidential election when Senator James Thomas Heflin embarked on a nationwide speaking tour, partially funded by the Ku Klux Klan, against Roman Catholic Democratic nominee Al Smith and supported Republican Herbert Hoover,[9] who went on to lose the state that year by only seven thousand votes.

Following Smith, Alabama’s loyalty to the national Democratic Party would be broken when Harry S. Truman, seeking a strategy to win the Cold War against the radically egalitarian rhetoric of Communism,[10] launched the first Civil Rights bill since Reconstruction. Southern Democrats became enraged and for the 1948 presidential election, Alabama’s Democratic presidential elector primary chose electors who were pledged to not vote for incumbent President Truman,[11] while the state Supreme Court ruled that any statute requiring party presidential electors to vote for that party's national nominee was void, with the result that Truman was entirely excluded from the Alabama ballot[12] despite a “Loyalist” group petitioning incumbent governor "Big Jim" Folsom to allow Truman electors on the ballot alongside the “Democratic” electors pledged to States’ Rights nominee Strom Thurmond.[13]

After Thurmond, running as the “Democratic” nominee, carried Alabama by a margin only slightly smaller than Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four victories, Dixiecrats would lose control of the state party to loyalists in 1950. For 1952, these loyalists would pledge state Democrats to support the national nominees, Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson and running mate, US Senator John Sparkman,[14] whilst unlike the other three states who voted for Thurmond, few Alabama Democrats would support Republican nominees Columbia University President Dwight D. Eisenhower and California Senator Richard Nixon.[15] Despite this, Eisenhower did briefly visit the state during September, and gained some public support over issues of taxation and the stalemated Korean War.[16]

- ^ "United States Presidential election of 1952 — Encyclopædia Britannica". Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. presidential election, 1952". Facts on File. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

Eisenhower, born in Texas, considered a resident of New York, and headquartered at the time in Paris, finally decided to run for the Republican nomination

- ^ "1952 Election for the Forty-Second Term (1953-57)". Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ Perman, Michael (2001). Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. Introduction.

- ^ Stanley, Harold Watkins (1987). Voter mobilization and the politics of race: the South and universal suffrage, 1952-1984. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 100. ISBN 0275926737.

- ^ a b Heersink, Boris; Jenkins, Jeffery A. (2020). Republican Party Politics and the American South, 1865-1968. Cambridge University Press. pp. 251–253. ISBN 9781107158436.

- ^ Casdorph, Paul D. (1981). Republicans, Negroes, and Progressives in the South, 1912-1916. The University of Alabama Press. pp. 70, 94–95. ISBN 0817300481.

- ^ Phillips, Kevin P. (1969). The Emerging Republican Majority. Arlington House. p. 255. ISBN 0870000586.

- ^ Chiles, Robert (2018). The Revolution of '28: Al Smith, American Progressivism, and the Coming of the New Deal. Cornell University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9781501705502.

- ^ Geselbracht, Raymond H., ed. (2007). The Civil Rights Legacy of Harry S. Truman. Truman State University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1931112673.

- ^ Jenkins, Ray (2012). Blind Vengeance: The Roy Moody Mail Bomb Murders. University of Georgia Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0820341019.

- ^ Key, V.O. junior; Southern Politics in State and Nation; p. 340 ISBN 087049435X

- ^ Barnard, William D. (November 30, 1984). Dixiecrats and Democrats: Alabama Politics 1942-50. University of Alabama Press. p. 123. ISBN 0817302557.

- ^ Barnard. Dixiecrats and Democrats. p. 142

- ^ Perman, Michael (2009). Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South. University of North Carolina Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0807833247.

- ^ Cornell, Douglas B. (October 24, 1952). "Most Southern States Continue to Back Demos Despite Sizeable Republican Inroads — GOP Has Even Chance to Carry Virginia, Texas, Florida". Lubbock Morning Avalanche. Lubbock, Texas. p. 11.