Back أكتيون تي4 Arabic T4 əməliyyatı Azerbaijani Праграма Т-4 Byelorussian Акция Т4 Bulgarian Aktion T4 Catalan Akce T4 Czech Aktion T4 Danish Aktion T4 German Πρόγραμμα Ευθανασίας T-4 Greek Aranĝo T4 Esperanto

| Aktion T4 | |

|---|---|

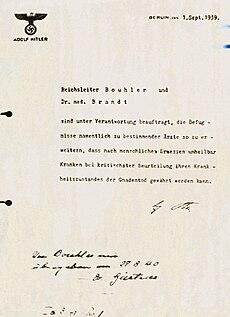

Hitler's order for Aktion T4 | |

| Also known as | T4 Program |

| Location | German-occupied Europe |

| Date | September 1939 – 1945 |

| Incident type | Forced euthanasia |

| Perpetrators | SS |

| Participants | Psychiatric hospitals |

| Victims | 275,000–300,000[1][2][3][a] |

Aktion T4 (German, pronounced [akˈtsi̯oːn teː fiːɐ]) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia which targeted people with disabilities in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings.[4] The name T4 is an abbreviation of Tiergartenstraße 4, a street address of the Chancellery department set up in early 1940, in the Berlin borough of Tiergarten, which recruited and paid personnel associated with Aktion T4.[5][b] Certain German physicians were authorised to select patients "deemed incurably sick, after most critical medical examination" and then administer to them a "mercy death" (Gnadentod).[7] In October 1939, Adolf Hitler signed a "euthanasia note", backdated to 1 September 1939, which authorised his physician Karl Brandt and Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler to begin the killing.

The killings took place from September 1939 until the end of the war in 1945; from 275,000 to 300,000 people were killed in psychiatric hospitals in Germany and Austria, occupied Poland and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (now the Czech Republic).[8] The number of victims was originally recorded as 70,273 but this number has been increased by the discovery of victims listed in the archives of the former East Germany.[9][c] About half of those killed were taken from church-run asylums, often with the approval of the Protestant or Catholic authorities of the institutions.[10]

The Holy See announced on 2 December 1940 that the policy was contrary to divine law and that "the direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed" but the declaration was not upheld by all Catholic authorities in Germany.[citation needed] In the summer of 1941, protests were led in Germany by the bishop of Münster, Clemens von Galen, whose intervention led to "the strongest, most explicit and most widespread protest movement against any policy since the beginning of the Third Reich", according to Richard J. Evans.[11]

Several reasons have been suggested for the killings, including eugenics, racial hygiene, and saving money.[12] Physicians in German and Austrian asylums continued many of the practices of Aktion T4 until the defeat of Germany in 1945, in spite of its official cessation in August 1941. The informal continuation of the policy led to 93,521 "beds emptied" by the end of 1941.[13][d] Technology developed under Aktion T4, particularly the use of lethal gas on large numbers of people, was taken over by the medical division of the Reich Interior Ministry, along with the personnel of Aktion T4, who participated in mass murder of Jewish people.[17] The programme was authorised by Hitler but the killings have since come to be viewed as murders in Germany. The number of people killed was about 200,000 in Germany and Austria, with about 100,000 victims in other European countries.[18] Following the war, a number of the perpetrators were tried and convicted for murder and crimes against humanity.

- ^ "Exhibition catalogue in German and English" (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Memorial for the Victims of National Socialist ›Euthanasia‹ Killings. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Euthanasia Program" (PDF). Yad Vashem. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b Chase, Jefferson (26 January 2017). "Remembering the 'forgotten victims' of Nazi 'euthanasia' murders". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Sandner 1999, p. 385.

- ^ Hojan & Munro 2015; Bialas & Fritze 2014, pp. 263, 281; Sereny 1983, p. 48.

- ^ Sereny 1983, p. 48.

- ^ Proctor 1988, p. 177.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 477; Browning 2005, p. 193; Proctor 1988, p. 191.

- ^ a b GFE 2013.

- ^ Evans 2009, p. 107; Burleigh 2008, p. 262.

- ^ Evans 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Burleigh & Wippermann 2014; Adams 1990, pp. 40, 84, 191.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 142; Ryan & Schuchman 2002, pp. 25, 62.

- ^ Burleigh 1995.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 142.

- ^ Ryan & Schuchman 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Lifton 2000, p. 102.

- ^ "Sources on the History of the "Euthanasia" crimes 1939–1945 in German and Austrian Archives" [Quellen zur Geschichte der "Euthanasie"-Verbrechen 1939–1945 in deutschen und österreichischen Archiven] (PDF). Bundesarchiv. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).