Back جدل إسقاط التكاليف Arabic Controversia antinomiana Spanish Антиномистский спор (1636-1638) Russian

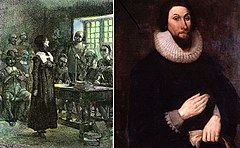

Anne Hutchinson at trial and John Winthrop | |

| Date | October 1636 to March 1638 |

|---|---|

| Location | Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Participants | Free Grace Advocates (sometimes called "Antinomians")

Magistrates Ministers |

| Outcome |

|

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of Puritan minister John Cotton. The most notable Free Grace advocates, often called "Antinomians", were Anne Hutchinson, her brother-in-law Reverend John Wheelwright, and Massachusetts Bay Governor Henry Vane. The controversy was a theological debate concerning the "covenant of grace" and "covenant of works".

Anne Hutchinson has historically been placed at the center of the controversy, a strong-minded woman who had grown up under the religious guidance of her father Francis Marbury, an Anglican clergyman and school teacher. In England, she embraced the religious views of dynamic Puritan minister John Cotton, who became her mentor; Cotton was forced to leave England and Hutchinson followed him to New England.

In Boston, Hutchinson was influential among the settlement's women and hosted them at her house for discussions on the weekly sermons. Eventually, men were included in these gatherings, such as Governor Vane. During the meetings, Hutchinson criticized the colony's ministers, accusing them of preaching a covenant of works as opposed to the covenant of grace espoused by Reverend Cotton. The Colony's orthodox ministers held meetings with Cotton, Wheelwright, and Hutchinson in the fall of 1636. A consensus was not reached, and religious tensions mounted.

To ease the situation, the leaders called for a day of fasting and repentance on 19 January 1637. However, Cotton invited Wheelwright to speak at the Boston church during services that day, and his sermon created a furor which deepened the growing division. In March 1637, the court accused Wheelwright of contempt and sedition, but he was not sentenced. His supporters (mostly people from the Boston church) circulated a petition on his behalf.

The religious controversy had immediate political ramifications. During the election of May 1637, the free grace advocates suffered two major setbacks when John Winthrop defeated Vane in the gubernatorial race, and some Boston magistrates were voted out of office for supporting Hutchinson and Wheelwright. Vane returned to England in August 1637. At the November 1637 court, Wheelwright was sentenced to banishment, and Hutchinson was brought to trial. She defended herself well against the prosecution, but she claimed on the second day of her hearing that she possessed direct personal revelation from God, and she prophesied ruin upon the colony. She was charged with contempt and sedition and banished from the colony, and her departure brought the controversy to a close. The events of 1636 to 1638 are regarded as crucial to an understanding of religion and society in the early colonial history of New England.

The idea that Hutchinson played a central role in the controversy went largely unchallenged until 2002, when Michael Winship's account portrayed Cotton, Wheelwright, and Vane as complicit with her.