Back Autonome Verwaltung von Nord- und Ostsyrien ALS الإدارة الذاتية لشمال وشرق سوريا Arabic Şimali və Şərqi Suriya Muxtar İdarəsi Azerbaijani قوزئی و دوغو سوریه موختار ایدارهسی AZB Сірыйскі Курдыстан Byelorussian Сырыйскі Курдыстан BE-X-OLD Демократична федерация на Северна Сирия Bulgarian Kurdistan Siria Breton Rožava BS Administració Autònoma del Nord i Est de Síria Catalan

Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

| |

|---|---|

| Status | De facto autonomous region of Syria |

| Capital | Ayn Issa[1][2] 36°23′7″N 38°51′34″E / 36.38528°N 38.85944°E |

| Largest city | Raqqa |

| Official languages | |

| Regional official languages |

|

| Government | Federated semi-direct democracy |

| |

| Legislature | Syrian Democratic Council |

| Autonomous region | |

• Transitional administration declared | 2013 |

• Cantons declare autonomy | January 2014 |

• Cantons declare federation | 17 March 2016 |

• New administration declared | 6 September 2018 |

| Area | |

• Total | 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi)[6] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 4,600,000[7] |

| Currency | Syrian pound (SYP) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Drives on | Right |

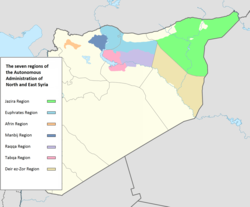

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), also known as Rojava,[b] is a de facto autonomous region in northeastern Syria.[12][13] It consists of self-governing sub-regions in the areas of Jazira, Euphrates, Raqqa, Tabqa, and Deir Ez-Zor.[14][15][16] The region gained its de facto autonomy in 2012 in the context of the ongoing Rojava conflict and the wider Syrian civil war, in which its official military force, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), has taken part.[17][18]

While entertaining some foreign relations, the region is neither officially recognized as autonomous by the government of Syria, state, or other governments institutions except for the Catalan Parliament.[19][20][21] The AANES has widespread support for its universal democratic, sustainable, autonomous, pluralist, equal, and feminist policies in dialogues with other parties and organizations.[22][23][24][25] Northeastern Syria is polyethnic and home to sizeable ethnic Arab, Kurdish, and Assyrian populations, with smaller communities of ethnic Turkmen, Armenians, Circassians, and Yazidis.[26][27][28]

The supporters of the region's administration state that it is an officially secular polity,[29][30][31] with direct democratic ambitions based on democratic confederalism and libertarian socialism,[32][33] promoting decentralization, gender equality,[34][35] environmental sustainability, social ecology, and pluralistic tolerance for religious, cultural, and political diversity, and that these values are mirrored in its constitution, society, and politics, stating it to be a model for a federalized Syria as a whole rather than outright independence.[36][37][38][39][40] The region's administration has also been accused by partisan and non-partisan sources of authoritarianism, media censorship, forced disappearances, support of the Ba'athist regime,[c] Kurdification, and displacement.[44] At the same time, the AANES has also been described by partisan and non-partisan sources as the most democratic system in Syria, with direct open elections, social equality, respecting human rights within the region, as well as defense of minority and religious rights within Syria.[d]

The region has implemented a new social justice approach, which emphasizes rehabilitation, empowerment, and social care over retribution. The death penalty was abolished. Prisons house mostly people charged with terrorist activity related to ISIL and other extremist groups, and are a large strain on the region's economy. The autonomous region is ruled by a coalition pursuing a model of economy that blends co-operative and market enterprise through a system of local councils in minority, cultural, and religious representation. Independent organizations providing healthcare in the region include the Kurdish Red Crescent,[51] the Syrian American Medical Society,[52] the Free Burma Rangers,[53] and Doctors Without Borders.[54] Since 2016, Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian rebel forces have occupied parts of northern Syria through a series of military operations against the SDF. AANES and its SDF have stated they would defend all regions of autonomous administration from any aggression.[55][56]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

kurdistan24newadminwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (23 November 2019). "Turkish-backed groups launch attack near strategic Syrian town of Ain Issa". Kurdistan24. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Fetah, Vîviyan (17 July 2018). "Îlham Ehmed: Dê rêxistinên me li Şamê jî ava bibin". rudaw.net (in Kurdish). Rudaw Media Network. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds declare new federation in bid for recognition". Middle East Eye. 17 March 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Amina Omar, Ryad Derrar elected as co-chairs of MSD – ANHA". Hawarnews. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "War Statistics / Syrian War Statistics – Syrian Civil War Map". Syrian Civil War Map – Live Middle East Map/ Map of the Syrian Civil War. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Salih, Mohammed A. (31 January 2024). "Syria's Kurdish Northeast Ratifies a New Constitution". New Lines Magazine. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ Lister (2015), p. 154.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), p. 89.

- ^ "'Rojava' no longer exists, 'Northern Syria' adopted instead". Kurdistan24. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

jazeera turkeywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 11, 95.

- ^ Zabad (2017), pp. 219, 228.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 97–98.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

electionsregionswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Delegation from the Democratic administration of Self-participate of self-participate in the first and second conference of the Shaba region". Cantonafrin.com. 4 February 2016. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "Turkey's Syria offensive explained in four maps". BBC News. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ "Syria Kurds adopt constitution for autonomous federal region". TheNewArab. 31 December 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

russia-mediateswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Umar: Catalonian recognition of AANES is the beginning". Hawar News Agency. 26 October 2021. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (21 October 2021). "Catalan parliament recognizes administration in northeast Syria". Kurdistan24. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ a b Shahvisi, Arianne (2018). "Beyond Orientalism: Exploring the Distinctive Feminism of democratic confederalism in Rojava" (PDF). Geopolitics. 26 (4): 1–25. doi:10.1080/14650045.2018.1554564. ISSN 1465-0045. S2CID 149972015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "German MP Jelpke: Rojava needs help against Corona pandemic". ANF News. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Şimşek, Bahar; Jongerden, Joost (29 October 2018). "Gender Revolution in Rojava: The Voices beyond Tabloid Geopolitics". Geopolitics. 26 (4): 1023–1045. doi:10.1080/14650045.2018.1531283. hdl:1887/87090.

- ^ Burç, Rosa (22 May 2020). "Non-territorial autonomy and gender equality: The case of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria – Rojava" (PDF). Philosophy and Society. 31 (3): 277–448. doi:10.2298/FID2003319B. S2CID 226412887. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. xviii, 112.

- ^ Zabad (2017), pp. 219, 228–229.

- ^ Schmidinger, Thomas (2019). The Battle for the Mountain of the Kurds (PDF). Translated by Schiffmann, Thomas. PM Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-62963-651-1.

Afrin was the home to the largest Ezidi minority in Syria.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. xviii, 66, 200.

- ^ "Syria Kurds challenging traditions, promote civil marriage". ARA News. 20 February 2016. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Dawronoyewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Colella, Chris (Winter 2017). "The Rojava Revolution: Oil, Water, and Liberation – Commodities, Conflict, and Cooperation". Commodities, Conflict, and Cooperation. Evergreen State College. Archived from the original on 23 July 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, David, eds. (2017). "Preface". Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red (2nd ed.). Oakland, California: PM Press. ISBN 978-1-62963-390-9.

- ^ Zabad (2017), p. 219.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 156–163.

- ^ "PYD leader: SDF operation for Raqqa countryside in progress, Syria can only be secular". ARA News. 28 May 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Ross, Carne (30 September 2015). "The Kurds' Democratic Experiment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ In der Maur, Renée; Staal, Jonas (2015). "Introduction". Stateless Democracy (PDF). Utrecht: BAK. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-77288-22-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost (6 December 2012). "Rethinking Politics and Democracy in the Middle East" (PDF). Ekurd.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

MiddleEastEyewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 94, 130–131, 184.

- ^ "Syria 2022". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021.

- ^ "Syria: Events of 2021". Human Rights Watch. 2022. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:4was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Knapp, Michael; Jongerden, Joost (2014). "Communal Democracy: The Social Contract and Confederalism in Rojava" (PDF). Comparative Islamic Studies. 10 (1): 87–109. doi:10.1558/cis.29642. ISSN 1740-7125.

- ^ Küçük, Bülent; Özselçuk, Ceren (1 January 2016). "The Rojava Experience: Possibilities and Challenges of Building a Democratic Life". South Atlantic Quarterly. 115 (1): 184–196. doi:10.1215/00382876-3425013. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2021 – via read.dukeupress.edu.

- ^ Barkhoda, Dalir (2016). "The Experiment of the Rojava System in Grassroots Participatory Democracy: Its Theoretical Foundation, Structure, and Strategies" (PDF). Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science. 4 (11): 80–88. ISSN 2321-9467.

- ^ Gerber, Damian; Brincat, Shannon (2018). "When Öcalan met Bookchin: The Kurdish Freedom Movement and the Political Theory of Democratic Confederalism". Geopolitics. 26 (4): 1–25. doi:10.1080/14650045.2018.1508016. S2CID 150297675.

- ^ "Nation-building in Rojava: participatory democracy amidst the Syrian civl war" (PDF). Imemo.ru. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "Ruptures and ripple effects in the Middle East and beyond" (PDF). Repository.bilkent.edu.tr. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "The medical care situation in Rojava". Cadus. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Smith, Noah (27 October 2019). "In Northern Syria, Destruction and Displacement Confront Health Workers". Direct Relief. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Bachelard, Michael (4 November 2019). "Free Burma Rangers activist and medic killed by Turkish drone strike in Syria". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Syria Crisis: MSF provides healthcare to Syrians crossing into Iraqi Kurdistan". Doctors Without Borders. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Kurdish-led SDF says Turkish invasion has revived IS, urges no-fly zone". Reuters. 12 October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "SDF-Turkey". Ahval. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

![Emblem[a] of North and East Syria](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e3/Emblem_of_the_Self_Administration_of_Northern_and_Eastern_Syria.svg/85px-Emblem_of_the_Self_Administration_of_Northern_and_Eastern_Syria.svg.png)