Back أبستاق Arabic الافيستا ARZ আৱেস্তা Assamese Avesta AST Avesta Azerbaijani Авеста Bashkir Авеста Byelorussian Авеста Bulgarian আবেস্তা Bengali/Bangla Avesta Catalan

| Avesta | |

|---|---|

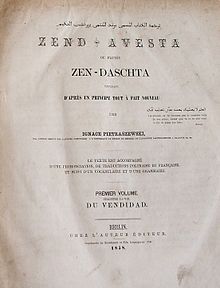

French translation of the Avesta by Polish Orientalist Ignacy Pietraszewski, Berlin, 1858. | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

| Language | Avestan |

| Period | c. 1500–c. 500 BCE (Avestan period) |

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Avesta (/əˈvɛstə/) is the primary collection of religious literature of Zoroastrianism,[1] in which all texts are composed in the Avestan language and are written in the Avestan alphabet.[2] It was compiled and redacted during the late Sassanian period (ca. 6th century CE)[3] although its individual texts were ″probably″ produced during the Old Iranian period (ca. 15th century BCE - 4th century BCE).[4] Before their compilation, these texts had been passed down orally for centuries.[5] The oldest surviving fragment of a text dates to 1323 CE.[2]

The Avesta texts fall into several different categories, arranged either by dialect, or by usage. The principal text in the liturgical group is the Yasna, which takes its name from the Yasna ceremony, Zoroastrianism's primary act of worship, at which the Yasna text is recited. The most important portion of the Yasna texts are the five Gathas, consisting of seventeen hymns attributed to Zoroaster himself. These hymns, together with five other short Old Avestan texts that are also part of the Yasna, are in the Old (or 'Gathic') Avestan language. The remainder of the Yasna's texts are in Younger Avestan, which is not only from a later stage of the language, but also from a different geographic region.

Extensions to the Yasna ceremony include the texts of the Vendidad and the Visperad.[6] The Visperad extensions consist mainly of additional invocations of the divinities (yazatas),[7] while the Vendidad is a mixed collection of prose texts mostly dealing with purity laws.[7] Even today, the Vendidad is the only liturgical text that is not recited entirely from memory.[7] Some of the materials of the extended Yasna are from the Yashts,[7] which are hymns to the individual yazatas. Unlike the Yasna, Visperad and Vendidad, the Yashts and the other lesser texts of the Avesta are no longer used liturgically in high rituals. Aside from the Yashts, these other lesser texts include the Nyayesh texts, the Gah texts, the Siroza and various other fragments. Together, these lesser texts are conventionally called Khordeh Avesta or "Little Avesta" texts. When the first Khordeh Avesta editions were printed in the 19th century, these texts (together with some non-Avestan language prayers) became a book of common prayer for lay people.[6]

The term Avesta originates from the 9th/10th-century works of Zoroastrian tradition in which the word appears as Middle Persian abestāg,[8][9] Book Pahlavi ʾp(y)stʾkʼ. In that context, abestāg texts are portrayed as received knowledge and are distinguished from the exegetical commentaries (the zand) thereof. The literal meaning of the word abestāg is uncertain; it is generally acknowledged to be a learned borrowing from Avestan, but none of the suggested etymologies have been universally accepted. The widely repeated derivation from *upa-stavaka is from Christian Bartholomae (Altiranisches Wörterbuch, 1904), who interpreted abestāg as a descendant of a hypothetical reconstructed Old Iranian word for "praise-song" (Bartholomae: Lobgesang); but this word is not actually attested in any text.

- ^ Kellens 1987, p. 35–44.

- ^ a b Boyce 1984, p. 1.

- ^ Hintze, Almut. "71. Book Chapter: "On editing the Avesta". In: A. Cantera (ed.), The Transmission of the Avesta. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2012, 419–432 (Iranica 20)". Iranica 20.

- ^ Cantera, Alberto (2012). "Preface". In Cantera, Alberto (ed.). The transmission of the Avesta. Iranica. Vol. 20. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-06554-2.

The Avestan texts were probably composed in Eastern Iran between the second half of the 2nd millennium bce and the end of the Achaemenid dynasty.

- ^ Skjaervo, P. Oktor (2012). "The Zoroastrian Oral Tradition as Reflected in the Texts". In Cantera, Alberto (ed.). The Transmission of the Avesta. Iranica. Vol. 20. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 3–48. ISBN 978-3-447-06554-2.

- ^ a b Boyce 1984, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Boyce 1984, p. 2.

- ^ Kellens 1987a, p. 239.

- ^ Cantera 2015.