Back مملكة أيوثايا Arabic Reinu d'Ayutthaya AST Ayutiya krallığı Azerbaijani آیوتتهایا شاهلیغی AZB Аютия (дәүләт) Bashkir অয়ুধ্যা রাজ্য Bengali/Bangla Regne d'Ayutthaya Catalan Ajutthajské království Czech Königreich Ayutthaya German Aĝuthaja Esperanto

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Ayutthaya Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1351–1767 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Trade flag (1680–1767)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

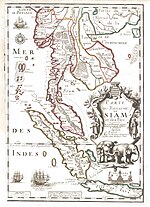

Ayutthaya and mainland Southeast Asia in 1540; Southeast Asian borders remained relatively undefined until the modern period | |||||||||||||||||||||

Map of Ayutthaya Kingdom during the reign of King Narai the Great | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Krung Tai | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Mandala kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1351–1369 (first) | Uthong | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1448–1488 | Ramesuan | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1590–1605 | Naresuan | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1629–1655 | Prasat Thong | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1656–1688 | Narai | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1688–1703 | Phetracha | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1758–1767 (last) | Ekkathat | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Viceroy | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1438–1448 (first) | Ramesuan | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1757–1758 (last) | Phonphinit | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-classical era, early modern era | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Foundation of Ayodhya | 934[i] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• First mentioned in Burmese chronicle | 1056[14][15] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• First mentioned in Đại Việt source | 1149[16] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• First tributary embassy to China | 1292[a][17] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Invasions of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra | 1290s–1490s[18] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Invasions of Champa | 1313[19]–1315[20]: 121–3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Kingdom official establishment | 4 March 1351[21] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Lopburi and Suphanburi rivalry | 1370–1409 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Union with the Northern Cities | 1378–1569[b][22] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Vassal of the Toungoo dynasty | 1564–68, 1569–84 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Golden Age of Ayutthaya | 1605–1767[22] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Invasions from Konbaung | 1759–60, 1765–67 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 April 1767 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 500.000 km2 (193.051 sq mi) (111th) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 1600[23] | ~2,500,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Photduang | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

The Ayutthaya Kingdom[ii] or the Empire of Ayutthaya[24] was a Mon–Siamese kingdom that existed in Southeast Asia from 1351[21][25][26] to 1767, centered around the city of Ayutthaya, in Siam, or present-day Thailand. European travellers in the early 16th century called Ayutthaya one of the three great powers of Asia (alongside Vijayanagara and China).[21][27] The Ayutthaya Kingdom is considered to be the precursor of modern Thailand, and its developments are an important part of the history of Thailand.[21]

The Ayutthaya Kingdom emerged from the mandala or merger of three maritime city-states on the Lower Chao Phraya Valley in the late 13th and 14th centuries (Lopburi, Suphanburi, and Ayutthaya).[28] The early kingdom was a maritime confederation, oriented to post-Srivijaya Maritime Southeast Asia, conducting raids and tribute from these maritime states. After two centuries of political organization from the Northern Cities and a transition to a hinterland state, Ayutthaya centralized and became one of the great powers of Asia. From 1569 to 1584, Ayutthaya was a vassal state of Toungoo Burma, but quickly regained independence. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Ayutthaya emerged as an entrepôt of international trade and its cultures flourished. The reign of Narai (r. 1657–1688) was known for Persian and later, European, influence and the sending of the 1686 Siamese embassy to the French court of King Louis XIV. The Late Ayutthaya Period saw the departure of the French and English but growing prominence of the Chinese. The period was described as a "golden age" of Siamese culture and saw the rise in Chinese trade and the introduction of capitalism into Siam,[29] a development that would continue to expand in the centuries following the fall of Ayutthaya.[30][31]

Ayutthaya's failure to create a peaceful order of succession and the introduction of capitalism undermined the traditional organization of its elite and the old bonds of labor control which formed the military and government organization of the kingdom. In the mid-18th century, the Burmese Konbaung dynasty invaded Ayutthaya in 1759–1760 and 1765–1767. In April 1767, after a 14-month siege, the city of Ayutthaya fell to besieging Burmese forces and was completely destroyed, thereby ending the 417-year-old Ayutthaya Kingdom. Siam, however, quickly recovered from the collapse and the seat of Siamese authority was moved to Thonburi-Bangkok within the next 15 years.[30][32]

In foreign accounts, Ayutthaya was called "Siam",[33] but people of Ayutthaya called themselves Tai, and their kingdom Krung Tai (Thai: กรุงไท) meaning 'Tai country' (กรุงไท).[34] It was also referred to as Iudea in a painting requested by the Dutch East India Company.[35] The capital city of Ayutthaya is officially known as Krung Thep Dvaravati Si Ayutthaya (Thai: กรุงเทพทวารวดีศรีอยุธยา), as documented in historical sources.[36][37][38][39]

- ^ a b Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64, 69, 78. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ a b "The Siam Society Lecture: A History of Ayutthaya (28 June 2017)". Youtube. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–07. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ "The Siam Society Lecture: Uma Amizade Duradoura (31 May 2018)". YouTube. 27 April 2020.

6:14–6:40

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 127–129, 206. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ "The Siam Society Lecture: Uma Amizade Duradoura (31 May 2018)". YouTube. 27 April 2020.

50:02–50:52

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ a b Baker, Chris (2003). "Ayutthaya Rising: From Land or Sea?". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 34 (1): 41–62. doi:10.1017/S0022463403000031. ISSN 0022-4634. JSTOR 20072474. S2CID 154278025.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. i, 170–171. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2. "From 1600, peace paved the way for Ayutthaya to prosper as Asia's leading entrepot under an expansive mercantile absolutism."

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

gileswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

burmawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

ctextwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 46, 51. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ "大越史記全書 《卷之六》" [The Complete Historical Records of Dai Viet "Volume 6"]. 中國哲學書電子化計劃 (in Chinese). Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ Na Nakhon, Prasert (1998), เรื่องเกี่ยวกับศิลาจารึกสุโขทัย [Stories Related To The Sukhothai Stone Inscriptions] (Thesis) (in Thai), Bangkok: Kasetsart University, pp. 110–223, ISBN 974-86374-6-8, archived from the original on 11 November 2024, retrieved 30 October 2024 Alt URL

- ^ a b c d Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:7was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0521800860. "Siam's population must have increased from c. 2,500,000 in 1600 to 4,000,000 in 1800."

- ^ Wyatt 2003, p. 86.

- ^ "Ayutthaya | National Virtual Museum". Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ The Siam Society Lecture: A History of Ayutthaya (28 June 2017), 21 May 2020, retrieved 29 October 2023

- ^ "Reception of the Ambassador of Siam, 1686". Palace of Versailles. 22 June 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wyatt 2003, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0521800860. "From the early 1700s well into the 19th century Chinese not only dominated Siam's external trade..."

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:4was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Ayutthaya | Ancient Capital of Thailand | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Williams, Benjamin (5 October 2020). "Cultural Profile: Ayutthaya Kingdom, the Buddhist State of Siam". Paths Unwritten. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Roberts, Edmund (1837). "XVIII City of Bang-kok". Embassy to the Eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock during the years 1832–3–4. Harper & Brothers. p. image 288. OCLC 12212199.

The spot on which the present capital stands, and the country in its vicinity, on both banks of the river for a considerable distance, were formerly, before the removal of the court to its present situation called Bang-kok; but since that time, and for nearly sixty years past, it has been named Sia yuthia, (pronounced See-ah you-tè-ah, and by the natives, Krung, that is, the capital;) it is called by both names here, but never Bang-kok; and they always correct foreigners when the latter make this mistake. The villages which occupy the right hand of the river, opposite to the capital, pass under the general name of Bang-kok.

- ^ Boeles, J.J. (1964). "The King of Sri Dvaravati and His Regalia" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 52 (1): 102–103. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Pongsripian, Winai (1983). Traditional Thai historiography and its nineteenth century decline (PDF) (PhD). University of Bristol. p. 21. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Blagden, C.O. (1941). "A XVIIth Century Malay Cannon in London". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 19 (1): 122–124. JSTOR 41559979. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

TA-HTAUNG TA_YA HNIT-HSE SHIT-KHU DWARAWATI THEIN YA – 1128 year (= 1766 A.D) obtained at the conquest of Dwarawati (= Siam). One may note that in that year the Burmese invaded Siam and captured Ayutthaya, the capital, in 1767.

- ^ JARUDHIRANART, Jaroonsak (2017). THE INTERPRETATION OF SI SATCHANALAI (Thesis). Silpakorn University. p. 31. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

Ayutthaya, they still named the kingdom after its former kingdom as "Krung Thep Dvaravati Sri Ayutthaya".

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-roman> tags or {{efn-lr}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-roman}} template or {{notelist-lr}} template (see the help page).