Back معركة نافارين Arabic معركة نافارين ARZ Navarin döyüşü Azerbaijani Наваринско сражение Bulgarian Batalla de Navarino Catalan Bitva u Navarina Czech Slaget ved Navarino Danish Schlacht von Navarino German Ναυμαχία του Ναυαρίνου Greek Batalla de Navarino Spanish

| Battle of Navarino | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greek War of Independence | |||||||

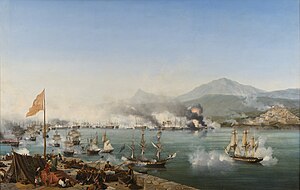

The Naval Battle of Navarino, Ambroise Louis Garneray | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

(OOB) 1,252 guns8,000 crewmen[1] |

3 ships of the line 17 frigates 30 corvettes 5 schooners 28 brigs 5–6 fireships (OOB) 2,158 guns 20,000 crewmen[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

181 killed 480 wounded |

4,000 killed or wounded 4,000 captured 55 ships lost[1] | ||||||

Location within Peloponnese | |||||||

The Battle of Navarino was a naval battle fought on 20 October (O.S. 8 October) 1827, during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), in Navarino Bay (modern Pylos), on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. Allied forces from Britain, France, and Russia decisively defeated Ottoman and Egyptian forces which were trying to suppress the Greeks, thereby making Greek independence much more likely. An Ottoman armada which, in addition to Imperial warships, included squadrons from the eyalets of Egypt and Regency of Algiers and Tunis,[a] was destroyed by an Allied force of British, French and Russian warships. It was the last major naval battle in history to be fought entirely with sailing ships, although most ships fought at anchor. The Allies' victory was achieved through superior firepower and gunnery.

The context of the three Great Powers' intervention in the Greek conflict was the Russian Empire's long-running expansion at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire. Russia's ambitions in the region were seen as a major geostrategic threat by the other European powers, which feared the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of Russian hegemony in the Eastern Mediterranean. The precipitating factor was support of elements in Orthodox Russia for Greek coreligionists, despite the opposition of Tsar Alexander in 1821 following the Greek rebellion against their Ottoman overlords. Similarly, despite official British interest in maintaining the Ottoman Empire, British public opinion strongly supported the Greeks. Fearing unilateral Russian action, Britain and France bound Russia, by treaty, to a joint intervention which aimed to secure Greek autonomy, whilst still preserving Ottoman territorial integrity as a check on Russia.

The Powers agreed, by the Treaty of London (1827), to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to the Eastern Mediterranean to enforce their policy. The naval battle happened more by accident than by design as a result of a manoeuvre by the Allied commander-in-chief, Admiral Edward Codrington, aimed at coercing the Ottoman commander to obey Allied instructions. The sinking of the Ottomans' Mediterranean fleet saved the fledgling Greek Republic from collapse. But it required two more military interventions, by Russia in the form of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 and a French expeditionary force to the Peloponnese to force the withdrawal of Ottoman forces from central and southern Greece, to finally secure Greek independence.

- ^ a b c Bodart 1908, p. 492.

- ^ John de Courcy Ireland (1976), "The Corsairs of North Africa", The Mariner's Mirror, 62 (3): 271–283, doi:10.1080/00253359.1976.10658971, at p. 281.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).