| Benzodiazepine overdose | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benzodiazepine poisoning |

| |

| US yearly overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines.[1] | |

| Specialty | Toxicology, emergency medicine |

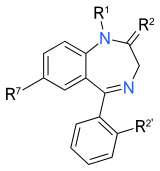

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

|

Benzodiazepine overdose (BZD OD) describes the ingestion of one of the drugs in the benzodiazepine class in quantities greater than are recommended or generally practiced. The most common symptoms of overdose include central nervous system (CNS) depression, impaired balance, ataxia, and slurred speech. Severe symptoms include coma and respiratory depression. Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment of benzodiazepine overdose. There is an antidote, flumazenil, but its use is controversial.[2]

Deaths from single-drug benzodiazepine overdoses occur infrequently,[3] particularly after the point of hospital admission.[4] However, combinations of high doses of benzodiazepines with alcohol, barbiturates, opioids or tricyclic antidepressants are particularly dangerous, and may lead to severe complications such as coma or death. In 2013, benzodiazepines were involved in 31% of the estimated 22,767 deaths from prescription drug overdose in the United States.[5] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has subsequently issued a black box warning regarding concurrent use of benzodiazepines and opioids.[6] Benzodiazepines are one of the most highly prescribed classes of drugs,[7] and they are commonly used in self-poisoning.[8][9] Over 10 years in the United Kingdom, 1512 fatal poisonings have been attributed to benzodiazepines with or without alcohol.[10] Temazepam was shown to be more toxic than the majority of benzodiazepines. An Australian (1995) study found oxazepam less toxic and less sedative, and temazepam more toxic and more sedative, than most benzodiazepines in overdose.[11]

- ^ Overdose Death Rates Archived 2015-11-28 at the Wayback Machine. By National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Segerwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dart, Richard C. (1 December 2003). Medical Toxicology (3rd ed.). US: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 811. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ^ Höjer J, Baehrendtz S, Gustafsson L (August 1989). "Benzodiazepine poisoning: experience of 702 admissions to an intensive care unit during a 14-year period". Journal of Internal Medicine. 226 (2): 117–22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb01365.x. PMID 2769176. S2CID 12787102.

- ^ Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, Starrels JL (April 2016). "Increasing Benzodiazepine Prescriptions and Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1996-2013". American Journal of Public Health. 106 (4): 686–8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303061. PMC 4816010. PMID 26890165.

- ^ Commissioner, Office of the. "Press Announcements - FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- ^ Taylor S, McCracken CF, Wilson KC, Copeland JR (November 1998). "Extent and appropriateness of benzodiazepine use. Results from an elderly urban community". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (5): 433–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.5.433. PMID 9926062. S2CID 2802139.

- ^ Ngo AS, Anthony CR, Samuel M, Wong E, Ponampalam R (July 2007). "Should a benzodiazepine antagonist be used in unconscious patients presenting to the emergency department?". Resuscitation. 74 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.11.010. PMID 17306436.

- ^ Jonasson B, Jonasson U, Saldeen T (January 2000). "Among fatal poisonings dextropropoxyphene predominates in younger people, antidepressants in the middle aged and sedatives in the elderly". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 45 (1): 7–10. doi:10.1520/JFS14633J. PMID 10641912.

- ^ Serfaty M, Masterton G (1993). "Fatal poisonings attributed to benzodiazepines in Britain during the 1980s". Br J Psychiatry. 163 (3): 386–93. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.3.386. PMID 8104653. S2CID 46001278.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Buckleywas invoked but never defined (see the help page).