Back يوليو الأسود Arabic Schwarzer Juli German Juillet noir French ब्लैक जुलाई Hindi ബ്ലാക്ക് ജൂലൈ Malayalam Black July NB Julho Negro Portuguese Чёрный июль Russian කළු ජූලිය Singhalese Black July SIMPLE

| Black July | |

|---|---|

| Part of riots in Sri Lanka, the Sri Lankan Civil War, and the Tamil genocide | |

| |

Location of Sri Lanka | |

| Location | Sri Lanka |

| Date | 24 July 1983 – 30 July 1983 (UTC+6) |

| Target | Primarily Sri Lankan Tamils |

Attack type | Pogrom, ethnic cleansing, mass murder, genocide, genocidal rape |

| Weapons | Axes, guns, explosives, knives, sticks |

| Deaths | 5,638 killed and 466 disappeared (acc. to TCHR) [4] |

| Injured | 2,015 and 670 raped (acc. to TCHR) [4] |

| Victims | Tamil civilians |

| Perpetrators | Sinhalese mobs, Sri Lankan government, UNP; Sri Lanka Armed Forces and Sri Lanka Police |

No. of participants | Thousands |

| Motive | Anti-Tamil racism, Sinhala nationalism |

| Anti-Tamil pogroms in Sri Lanka |

|---|

| Gal Oya (1956) |

| 1958 pogrom |

| 1977 pogrom |

| 1981 pogrom |

| Black July (1983) |

Black July (Tamil: கறுப்பு யூலை, romanized: Kaṟuppu Yūlai; Sinhala: කළු ජූලිය, romanized: Kalu Juliya) was an anti-Tamil pogrom[5] that occurred in Sri Lanka during July 1983.[6][7] The pogrom was premeditated,[8][9][10][11][note 1] and was finally triggered by a deadly ambush on a Sri Lankan Army patrol by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) on 23 July 1983, which killed 13 soldiers.[13] Although initially orchestrated by members of the ruling UNP, the pogrom soon escalated into mass violence with significant public participation.[14]

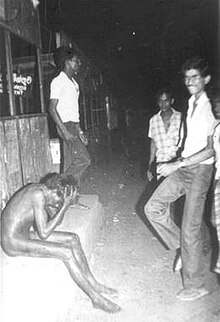

On the night of 24 July 1983, anti-Tamil rioting started in the capital city of Colombo and then spread to other parts of the country. Over seven days, mainly Sinhalese mobs attacked, burned, looted, and killed Tamil civilians. The looting, arson and killings later spread to include all Indians, with the Indian High Commission being attacked and the Indian Overseas Bank being completely destroyed.[15] Estimates of the death toll range between 400 and 3,000,[16] and 150,000 people became homeless.[17][18] According to Tamil Centre for Human Rights (TCHR), the total number of Tamils killed in the Black July pogrom was 5,638.[4]

Around 18,000 homes and 5,000 shops were destroyed.[19] The economic cost of the riots was estimated to be $300 million.[17] The pogrom was organised to destroy the economic base of the Tamils, with every Tamil owned shop and establishment being plundered and set alight.[15] The NGO International Commission of Jurists described the violence of the pogrom as having "amounted to acts of genocide" in a report published in December 1983.[20]

The pogrom spurred thousands of Tamil youth to spontaneously join militant groups, which prior to the pogrom had only 20-30 members.[16][21] Black July is generally seen as the start of the Sri Lankan Civil War between the Tamil militants and the government of Sri Lanka.[18][22] Sri Lankan Tamils fled to other countries in the ensuing years, with July becoming a period of remembrance for the diaspora around the world.[23] To date no one has been held accountable for any of the crimes committed during the pogrom.[24]

- ^ "Visual Evidence I: Vitality, Value and Pitfall – Borella Junction, 24/25 July 1983". 29 October 2011.

- ^ "Black July 1983 remembered". Tamil Guardian. 23 July 2014.

- ^ Jeyaraj, D. B. S. (24 July 2010). "Horror of a pogrom: Remembering "Black July" 1983". dbsjeyaraj.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "Recorded figures of Arrests, Killings, Disappearances".

- ^ Community, Gender and Violence, edited by Partha Chatterjee, Pradeep Jeganathan

- ^ Rajan Hoole, Black July: Further Evidence Of Advance Planning https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/black-july-further-evidence-of-advance-planning/

- ^ Rajan Hoole, Sri Lanka’s Black July: Borella, 24th Evening https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/sri-lankas-black-july-borella-24th-evening/

- ^ T. Sabaratnam, Pirapaharan, Volume 2, Chapter 2 – The Jaffna Massacre (2003)

- ^ T. Sabaratnam, Pirapaharan, Volume 2, Chapter 3 – The Final Solution (2003)

- ^ T. Sabaratnam, Pirapaharan, Volume 2, Chapter 4 – Massacre of Prisoners (2003)

- ^ T. Sabaratnam, Pirapaharan, Volume 2, Chapter 5 – The Second Massacre (2003)

- ^ A. Jeyaratnam Wilson, The Break-up of Sri Lanka: The Sinhalese-Tamil Conflict. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988. p.173

- ^ Nidheesh, MK (2 September 2016). "Book review: The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi by Neena Gopal". Live Mint. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ E.M. Thornton & Niththyananthan, R. – Sri Lanka, Island of Terror – An Indictment, (ISBN 0 9510073 0 0), 1984, Appendix A

- ^ a b Pratap, Anita (August 1983). "A drop of blood in the Indian Ocean". Sunday, Vol. 11, No. 4. India. pp.34-39

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

BBC230703was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Aspinall, Jeffrey & Regan 2013, p. 104.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

BBC230708was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Peace and Conflict Timeline: 24 July 1983". Centre for Poverty Analysis. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "ICJ Review no. 31 (December 1983)" (PDF). p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2014.

- ^ Sivakumar, Chitra (2001). Transformation in the Sri Lankan Tamil Militant Discourse. Madras: University of Madras. p.323

- ^ Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1986). Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-78952-7.

- ^ "Black July '83". Blackjuly83.com. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Ghosts of Black July still haunt Sri Lanka". Daily FT. Colombo. 26 July 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).