Back Brexit Afrikaans Brexit ALS Brexit AN انسحاب المملكة المتحدة من الاتحاد الأوروبي Arabic بريكزيت ARZ ব্ৰেক্সিট Assamese Salida del Reinu Xuníu de la Xunión Europea AST Böyük Britaniyanın Avropa İttifaqından çıxışı Azerbaijani Brexit BAT-SMG Выхад Вялікабрытаніі з Еўрапейскага саюза Byelorussian

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

|

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| UK membership of the European Union (1973–2020) |

|---|

|

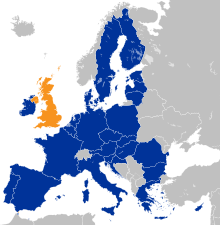

Brexit (/ˈbrɛksɪt, ˈbrɛɡzɪt/,[1] a portmanteau of "British exit") was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union.

Following a referendum held in the UK on 23 June 2016, Brexit officially took place at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 CET).[a] The UK, which joined the EU's precursors the European Communities (EC) on 1 January 1973, is the only member state to have withdrawn from the EU. Following Brexit, EU law and the Court of Justice of the European Union no longer have primacy over British laws. The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 retains relevant EU law as domestic law, which the UK can amend or repeal.

The EU and its institutions developed gradually after their establishment. Throughout the period of British membership, Eurosceptic groups had existed in the UK, opposing aspects of the EU and its predecessors. The Labour prime minister Harold Wilson's pro-EC government held a referendum on continued EC membership in 1975, in which 67.2 per cent of those voting chose to stay within the bloc. Despite growing political opposition to further European integration aimed at "ever closer union" between 1975 and 2016, notably from factions of the Conservative Party in the 1980s to 2000s, no further referendums on the issue were held.

By the 2010s, the growing popularity of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), as well as pressure from Eurosceptics in his own party, persuaded the Conservative prime minister David Cameron to promise a referendum on British membership of the EU if his government were re-elected. Following the 2015 general election, which produced a small but unexpected overall majority for the governing Conservative Party, the promised referendum on continued EU membership was held on 23 June 2016. Notable supporters of the Remain campaign included Cameron, the future prime ministers Theresa May and Liz Truss, and the ex–prime ministers John Major, Tony Blair, and Gordon Brown; notable supporters of the Leave campaign included the future prime ministers Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak. The electorate voted to leave the EU with a 51.9% share of the vote, with all regions of England and Wales except London voting in favour of Brexit, and Scotland and Northern Ireland voting against. The result led to Cameron's sudden resignation, his replacement by Theresa May, and four years of negotiations with the EU on the terms of departure and on future relations, completed under a Boris Johnson government, with government control remaining with the Conservative Party during this period.

The negotiation process was both politically challenging and deeply divisive within the UK, leading to two snap elections in 2017 and 2019. One deal was overwhelmingly rejected by the British parliament, causing great uncertainty and leading to postponement of the withdrawal date to avoid a no-deal Brexit. The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020 after a withdrawal deal was passed by Parliament, but continued to participate in many EU institutions (including the single market and customs union) during an eleven-month transition period in order to ensure frictionless trade until all details of the post-Brexit relationship were agreed and implemented. Trade deal negotiations continued within days of the scheduled end of the transition period, and the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement was signed on 30 December 2020. The effects of Brexit are in part determined by the cooperation agreement, which provisionally applied from 1 January 2021, until it formally came into force on 1 May 2021.[2]

- ^ Hall, Damien (11 August 2017). "'Breksit' or 'bregzit'? The question that divides a nation". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement: Council adopts decision on conclusion". www.consilium.europa.eu. 29 April 2021. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).