Back ديكارتية Arabic Karteziançılıq Azerbaijani Cartesianisme Catalan Cartesianismus German Cartesianismo Spanish Kartesianismo Basque دکارتگرایی Persian Kartesiolaisuus Finnish Cartésianisme French डेकार्टवाद Hindi

| Part of a series on |

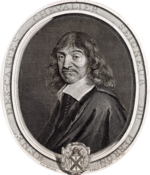

| René Descartes |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

Cartesianism is the philosophical and scientific system of René Descartes and its subsequent development by other seventeenth century thinkers, most notably François Poullain de la Barre, Nicolas Malebranche and Baruch Spinoza.[1] Descartes is often regarded as the first thinker to emphasize the use of reason to develop the natural sciences.[2] For him, philosophy was a thinking system that embodied all knowledge.[3]

Aristotle and St. Augustine's work influenced Descartes's cogito argument.[4][failed verification][5] Additionally, there is similarity between Descartes's work and that of Scottish philosopher George Campbell's 1776 publication, titled Philosophy of Rhetoric.[6] In his Meditations on First Philosophy he writes, "[b]ut what then am I? A thing which thinks. What is a thing which thinks? It is a thing which doubts, understands, [conceives], affirms, denies, wills, refuses, which also imagines and feels."[7]

Cartesians view the mind as being wholly separate from the corporeal body. Sensation and the perception of reality are thought to be the source of untruth and illusions, with the only reliable truths to be had in the existence of a metaphysical mind. Such a mind can perhaps interact with a physical body, but it does not exist in the body, nor even in the same physical plane as the body. The question of how mind and body interact would be a persistent difficulty for Descartes and his followers, with different Cartesians providing different answers.[8] To this point Descartes wrote, "we should conclude from all this, that those things which we conceive clearly and distinctly as being diverse substances, as we regard mind and body to be, are really substances essentially distinct one from the other; and this is the conclusion of the Sixth Meditation."[7] Therefore, we can see that, while mind and body are indeed separate, because they can be separated from each other, but, Descartes postulates, the mind is a whole, inseparable from itself, while the body can become separated from itself to some extent, as in when one loses an arm or a leg.

- ^ Caird 1911, p. 414.

- ^ Grosholz, Emily (1991). Cartesian method and the problem of reduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-824250-6.

But contemporary debate has tended to...understand [Cartesian method] merely as the 'method of doubt'...I want to define Descartes's method in broader terms...to trace its impact on the domains of mathematics and physics as well as metaphysics.

- ^ Descartes, René; Translator John Veitch. "Letter of the Author to the French Translator of the Principles of Philosophy serving for a preface". Retrieved 18 August 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ Steup, Matthias (2018), "Epistemology", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, archived from the original on 22 September 2019, retrieved 17 April 2019

- ^ Menn, Stephen (2002). Descartes and Augustine. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0521012848.

On the face of it, Descartes' philosophy bears many resemblances to the thought of Augustine. Indeed, we know of several people who within Descartes' lifetime were sufficiently struck by these resemblances to call them to Descartes' attention...First, in order that we may begin with the things which are most manifest, I ask you whether you yourself exist. Are you afraid that you will be deceived in this questioning, seeing that you certainly cannot be deceived if you do not exist?

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - In Our Time, Cogito Ergo Sum". BBC. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ a b Descartes, Rene (1996). Meditations on First Philosophy (PDF). Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. p. 10.

- ^ "Cartesianism | philosophy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 January 2016.