Back كريستوفر لاش Arabic كريستوفر لاش ARZ Christopher Lasch Catalan Christopher Lasch Czech Christopher Lasch German Christopher Lasch Spanish Christopher Lasch Finnish Christopher Lasch French Christopher Lasch Italian クリストファー・ラッシュ Japanese

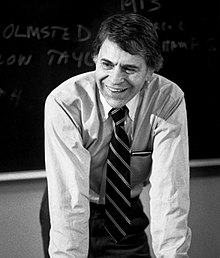

Christopher Lasch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Robert Christopher Lasch June 1, 1932 Omaha, Nebraska, US |

| Died | February 14, 1994 (aged 61) |

| Spouse |

Nell Commager (m. 1956) |

| Children | 4 |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Thesis | Revolution and Democracy[1] (1961) |

| Doctoral advisor | William Leuchtenburg[2][3] |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | History |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students | |

| Notable works | The Culture of Narcissism (1979) |

| Influenced | |

Robert Christopher Lasch (June 1, 1932 – February 14, 1994) was an American historian, moralist and social critic who was a history professor at the University of Rochester. He sought to use history to demonstrate what he saw as the pervasiveness with which major institutions, public and private, were eroding the competence and independence of families and communities. Lasch strove to create a historically informed social criticism that could teach Americans how to deal with rampant consumerism, proletarianization, and what he famously labeled "the culture of narcissism".

His books, including The New Radicalism in America (1965), Haven in a Heartless World (1977), The Culture of Narcissism (1979), The True and Only Heaven (1991), and The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (published posthumously in 1995) were widely discussed and reviewed. The Culture of Narcissism became a surprise best-seller and won the National Book Award in the category Current Interest (paperback).[6][a]

Lasch was always a critic of modern liberalism and a historian of liberalism's discontents, but over time, his political perspective evolved dramatically. In the 1960s, he was a neo-Marxist and acerbic critic of Cold War liberalism. Beginning in the 1970s, he combined certain aspects of cultural conservatism with a left-leaning critique of capitalism, and drew on Freud-influenced critical theory to diagnose the ongoing deterioration that he perceived in American culture and politics. His writings are sometimes denounced by feminists[7] and hailed by conservatives[8] for his apparent defense of a traditional conception of family life.

He eventually concluded that an often unspoken, but pervasive, faith in "Progress" tended to make Americans resistant to many of his arguments. In his last major works he explored this theme in depth, suggesting that Americans had much to learn from the suppressed and misunderstood populist and artisan movements of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[9]

- ^ Lasch, Christopher (1961). Revolution and Democracy: The Russian Revolution and the Crisis of American Liberalism, 1917–1919 (PhD thesis). New York: Columbia University. OCLC 893274321.

- ^ Mattson, Kevin (2003). "The Historian as a Social Critic: Christopher Lasch and the Uses of History". The History Teacher. 36 (3): 378. doi:10.2307/1555694. ISSN 1945-2292. JSTOR 1555694.

- ^ a b c Mattson, Kevin (March 31, 2017). "An Oracle for Trump's America?". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Vol. 63, no. 30. Washington. ISSN 0009-5982. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Byers, Paula K., ed. (1998). "Christopher Lasch". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-7876-2549-8. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Mattson, Kevin (1998). Creating a Democratic Public: The Struggle for Urban Participatory Democracy During the Progressive Era 1st Edition. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-271-01723-5.

- ^

"National Book Awards – 1980". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-09.

There was a "Contemporary" or "Current" award category from 1972 to 1980. - ^ Hartman (2009)

- ^ Jeremy Beer, "On Christopher Lasch," Modern Age, Fall 2005, Vol. 47 Issue 4, pp 330-343

- ^ Miller, Eric (2010). Hope in a Scattering Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0802817693.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).