Back Chroniese obstruktiewe longsiekte Afrikaans Chronisch obstruktive Lungenerkrankung ALS Malautía polmonar obstructiva cronica AN داء الانسداد الرئوي المزمن Arabic ক্ৰনিক অবষ্ট্ৰাক্টিভ পালমোনাৰী ডিজিজ Assamese Enfermedá pulmonar obstructiva crónica AST Ağciyərlərin xroniki obstruktiv xəstəliyi Azerbaijani آغجییرین کرونیک آبستراکتیو مریضلیگی AZB Хроник обструктив үпкә ауырыуы Bashkir Rauchabeischl BAR

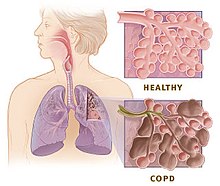

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a type of progressive lung disease characterized by chronic respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation.[8] GOLD 2024 defined COPD as a heterogeneous lung condition characterized by chronic respiratory symptoms (dyspnea or shortness of breath, cough, sputum production or exacerbations) due to abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) or alveoli (emphysema) that cause persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction.[9]

The main symptoms of COPD include shortness of breath and a cough, which may or may not produce mucus.[4] COPD progressively worsens, with everyday activities such as walking or dressing becoming difficult.[3] While COPD is incurable, it is preventable and treatable. The two most common types of COPD are emphysema and chronic bronchitis and have been the two classic COPD phenotypes. However, this basic dogma has been challenged as varying degrees of co-existing emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and potentially significant vascular diseases have all been acknowledged in those with COPD, giving rise to the classification of other phenotypes or subtypes.[10]

Emphysema is defined as enlarged airspaces (alveoli) whose walls have broken down resulting in permanent damage to the lung tissue. Chronic bronchitis is defined as a productive cough that is present for at least three months each year for two years. Both of these conditions can exist without airflow limitation when they are not classed as COPD. Emphysema is just one of the structural abnormalities that can limit airflow and can exist without airflow limitation in a significant number of people.[11][12] Chronic bronchitis does not always result in airflow limitation. However, in young adults with chronic bronchitis who smoke, the risk of developing COPD is high.[13] Many definitions of COPD in the past included emphysema and chronic bronchitis, but these have never been included in GOLD report definitions.[14] Emphysema and chronic bronchitis remain the predominant phenotypes of COPD but there is often overlap between them and a number of other phenotypes have also been described.[10][15] COPD and asthma may coexist and converge in some individuals.[16] COPD is associated with low-grade systemic inflammation.[17]

The most common cause of COPD is tobacco smoking.[18] Other risk factors include indoor and outdoor air pollution including dust, exposure to occupational irritants such as dust from grains, cadmium dust or fumes, and genetics, such as alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.[13][19] In developing countries, common sources of household air pollution are the use of coal and biomass such as wood and dry dung as fuel for cooking and heating.[20][13] The diagnosis is based on poor airflow as measured by spirometry.[4]

Most cases of COPD can be prevented by reducing exposure to risk factors such as smoking and indoor and outdoor pollutants.[21] While treatment can slow worsening, there is no conclusive evidence that any medications can change the long-term decline in lung function.[6] COPD treatments include smoking cessation, vaccinations, pulmonary rehabilitation, inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids.[6] Some people may benefit from long-term oxygen therapy, lung volume reduction and lung transplantation.[22] In those who have periods of acute worsening, increased use of medications, antibiotics, corticosteroids and hospitalization may be needed.[23]

As of 2015, COPD affected about 174.5 million people (2.4% of the global population).[7] It typically occurs in males and females over the age of 35–40.[1][3] In 2019 it caused 3.2 million deaths, 80% occurring in lower and middle income countries,[3] up from 2.4 million deaths in 1990.[24][25] In 2021, it was the fourth biggest cause of death, responsible for approximately 5% of total deaths.[26] The number of deaths is projected to increase further because of continued exposure to risk factors and an aging population.[14] In the United States in 2010 the economic cost was put at US$32.1 billion and projected to rise to US$49 billion in 2020.[27] In the United Kingdom this cost is estimated at £3.8 billion annually.[28]

- ^ a b c d e "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". nice.org. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

BMJbpwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)". Fact Sheets. World Health Organization. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Gold Report 2021, pp. 20–27, Chapter 2: Diagnosis and initial assessment.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 33–35, Chapter 2: Diagnosis and initial assessment.

- ^ a b c d e Gold Report 2021, pp. 40–46, Chapter 3: Evidence supporting prevention and maintenance therapy.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ 2024 GOLD Report, p. 15, Chapter 1: Definition and overview.

- ^ "2024 GOLD Report". Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ a b Myc LA, Shim YM, Laubach VE, Dimastromatteo J (April 2019). "Role of medical and molecular imaging in COPD". Clin Transl Med. 8 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s40169-019-0231-z. PMC 6465368. PMID 30989390.

- ^ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Martini K, Frauenfelder T (November 2020). "Advances in imaging for lung emphysema". Ann Transl Med. 8 (21): 1467. doi:10.21037/atm.2020.04.44. PMC 7723580. PMID 33313212.

- ^ a b c Gold Report 2021, pp. 8–14, Chapter 1: Definition and overview.

- ^ a b Gold Report 2021, pp. 4–8, Chapter 1: Definition and overview.

- ^ De Rose V, Molloy K, Gohy S, Pilette C, Greene CM (2018). "Airway Epithelium Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis and COPD". Mediators Inflamm. 2018: 1309746. doi:10.1155/2018/1309746. PMC 5911336. PMID 29849481.

- ^ GINA and GOLD joint guidelines Ga (2014). "Asthma COPD and asthma COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS)" (PDF). GINA Guidelines.

- ^ Agusti À, Soriano JB (January 2008). "COPD as a Systemic Disease". COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 5 (2): 133–138. doi:10.1080/15412550801941349. ISSN 1541-2555. PMID 18415812. S2CID 32732993.

- ^ "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) - Aetiology | BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "COPD causes - occupations and substances". www.hse.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Torres-Duque CA, García-Rodriguez MC, González-García M (August 2016). "Is Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Caused by Wood Smoke a Different Phenotype or a Different Entity?". Archivos de Bronconeumologia. 52 (8): 425–31. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2016.04.004. PMID 27207325.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 80–83, Chapter 4: Management of stable COPD.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 60–65, Chapter 3: Evidence supporting prevention and maintenance therapy.

- ^ Dobler CC, Morrow AS, Beuschel B, Farah MH, Majzoub AM, Wilson ME, et al. (March 2020). "Pharmacologic Therapies in Patients With Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 172 (6): 413–422. doi:10.7326/M19-3007 (inactive 7 December 2024). PMID 32092762. S2CID 211476101.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ "The top 10 causes of death". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-08-12.

- ^ "COPD Costs". www.cdc.gov. 5 July 2019. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020.

- ^ "COPD commissioning toolkit" (PDF). www.assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2021.