Back Sirkelredenasie Afrikaans استدلال دائري Arabic Кръгова логика Bulgarian Argumentació circular Catalan بەڵگەھێنانەوەی بازنەیی CKB Cirkulær argumentation Danish Zirkelschluss German Circulus in demonstrando DIQ Φαύλος κύκλος Greek Falacia circular Spanish

| Part of a series on |

| Pyrrhonism |

|---|

|

|

|

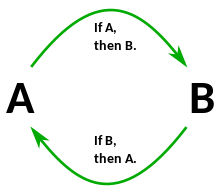

Circular reasoning (Latin: circulus in probando, "circle in proving";[1] also known as circular logic) is a logical fallacy in which the reasoner begins with what they are trying to end with.[2] Circular reasoning is not a formal logical fallacy, but a pragmatic defect in an argument whereby the premises are just as much in need of proof or evidence as the conclusion. As a consequence, the argument becomes a matter of faith and fails to persuade those who don't already accept it. Other ways to express this are that there is no reason to accept the premises unless one already believes the conclusion, or that the premises provide no independent ground or evidence for the conclusion.[3] Circular reasoning is closely related to begging the question, and in modern usage the two generally refer to the same thing.[4]

Circular reasoning is often of the form: "A is true because B is true; B is true because A is true." Circularity can be difficult to detect if it involves a longer chain of propositions.

An example of circular reasoning is: "Alkaline water is healthy because it results in health benefits, and it has health benefits because it is healthy".

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 389.

- ^ Dowden, Bradley (27 March 2003). "Fallacies". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ Nolt, John Eric; Rohatyn, Dennis; Varzi, Achille (1998). Schaum's outline of theory and problems of logic. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 205. ISBN 9780070466494.

- ^ Walton, Douglas (2008). Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521886178.