Back كوتن ميذر Arabic كوتن ميذر ARZ Cotton Mather Catalan Cotton Mather Czech Cotton Mather German Cotton Mather Esperanto Cotton Mather Spanish کاتن ماتر Persian Cotton Mather Finnish Cotton Mather French

Cotton Mather | |

|---|---|

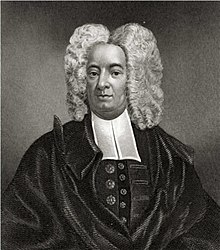

Mather, c. 1700 | |

| Born | February 12, 1663 |

| Died | February 13, 1728 (aged 65) Boston, Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Resting place | Copp's Hill Burying Ground, Boston |

| Education | Harvard College (AB, 1678; MA, 1681) |

| Occupation(s) | Minister, writer |

| Parent(s) | Increase Mather and Maria Cotton |

| Relatives | John Cotton (maternal grandfather) Richard Mather (paternal grandfather) Albert D. Mather (descendant)[1] |

| Signature | |

Cotton Mather FRS (/ˈmæðər/; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting House in Boston, Massachusetts, where he preached for the rest of his life. He has been referred to as the "first American Evangelical".[2]

A major intellectual and public figure in English-speaking colonial America, Cotton Mather helped lead the successful revolt of 1689 against Sir Edmund Andros, the governor of New England appointed by King James II. Mather's subsequent involvement in the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693, which he defended in the book Wonders of the Invisible World (1693), attracted intense controversy in his own day and has negatively affected his historical reputation. As a historian of colonial New England, Mather is noted for his Magnalia Christi Americana (1702).

Personally and intellectually committed to the waning social and religious orders in New England, Cotton Mather unsuccessfully sought the presidency of Harvard College. After 1702, Cotton Mather clashed with Joseph Dudley, the governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, whom Mather attempted unsuccessfully to drive out of power. Mather championed the new Yale College as an intellectual bulwark of Puritanism in New England. He corresponded extensively with European intellectuals and received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from the University of Glasgow in 1710.[3]

A promoter of the new experimental science in America, Cotton Mather carried out original research on plant hybridization. He also researched the variolation method of inoculation as a means of preventing smallpox contagion, which he learned about from an African-American slave who he owned, Onesimus. He dispatched many reports on scientific matters to the Royal Society of London, which elected him as a fellow in 1713.[4] Mather's promotion of inoculation against smallpox caused violent controversy in Boston during the outbreak of 1721. Scientist and United States Founding Father Benjamin Franklin, who as a young Bostonian had opposed the old Puritan order represented by Mather and participated in the anti-inoculation campaign, later described Mather's book Bonifacius, or Essays to Do Good (1710) as a major influence on his life.[5]

- ^ Biographical Directory of the South Dakota Legislature, 1889-1989: L-Z, The Council, 1989, p. 706

- ^ Kennedy, Rick (2015). The First American Evangelical: A Short Life of Cotton Mather. Eerdmans.

- ^ Silverman, Kenneth (2002) [1984]. The Life and Times of Cotton Mather. New York: Welcome Rain Publishers. p. 222. ISBN 1-56649-206-8.

- ^ Silverman 2002, pp. 253–254, 357.

- ^ Cohen, I. Bernard (1990). Benjamin Franklin's Science. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. p. 175. ISBN 0-674-06659-6.