Back التنوير المضاد Arabic Contrail·lustració Catalan Modoplysning Danish Gegenaufklärung German Contrailustración Spanish ضدروشنگری Persian Vastavalistus Finnish Contre-Lumières French הנאורות שכנגד HE Kontra-Pencerahan ID

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

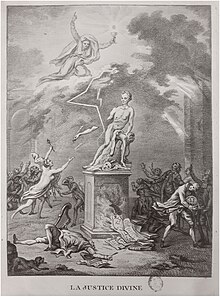

The Counter-Enlightenment refers to a loose collection of intellectual stances that arose during the European Enlightenment in opposition to its mainstream attitudes and ideals. The Counter-Enlightenment is generally seen to have continued from the 18th century into the early 19th century, especially with the rise of Romanticism. Its thinkers did not necessarily agree to a set of counter-doctrines but instead each challenged specific elements of Enlightenment thinking, such as the belief in progress, the rationality of all humans, liberal democracy, and the increasing secularisation of European society.

Scholars differ on who is to be included among the major figures of the Counter-Enlightenment. In Italy, Giambattista Vico criticised the spread of reductionism and the Cartesian method, which he saw as unimaginative and stiffling creative thinking.[1] Decades later, Joseph de Maistre in Sardinia and Edmund Burke in Britain both criticised the anti-religious ideas of the Enlightenment for leading to the Reign of Terror and an Orwellian police state following the French Revolution. The ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Georg Hamann were also significant to the rise of the Counter-Enlightenment with French and German Romanticism respectively.

In the late 20th century, the concept of the Counter-Enlightenment was popularised by pro-Enlightenment historian Isaiah Berlin[2] as a tradition of relativist, anti-rationalist, vitalist, and organic thinkers stemming largely from Hamann and subsequent German Romantics.[3] While Berlin is largely credited with having refined and promoted the concept, the first known use of the term in English occurred in 1949 and there were several earlier uses of it across other European languages,[4] including by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

- ^ Bertland, Alexander. "Giambattista Vico (1668—1744)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Garrard, Graeme (2006). Counter-enlightenments : from the eighteenth century to the present. Abingdon [England]: Routledge. ISBN 0203645669. OCLC 62895765.

- ^ Aspects noted by Darrin M. McMahon, "The Counter-Enlightenment and the Low-Life of Literature in Pre-Revolutionary France" Past and Present No. 159 (May 1998:77–112) p. 79 note 7.

- ^ listed by Henry Hardy in the second edition of Isaiah Berlin, Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas (Princeton University Press, 2013), p. xxv, note 1.