Back Dehidrasie Afrikaans Dehydratation (Medizin) ALS تجفاف Arabic Deshidratación AST دهیدراتاسیون AZB Дехидратация Bulgarian পানিশূন্যতা Bengali/Bangla Dehidracija BS Deshidratació Catalan وشکبوون لە لەش CKB

| Dehydration | |

|---|---|

| |

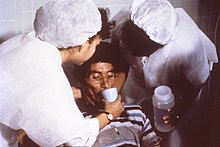

| Nurses encourage a patient to drink an oral rehydration solution to treat dehydration caused by cholera. | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Increased thirst, tiredness, decreased urine, dizziness, headaches, and confusion[1] |

| Complications | Low blood volume shock (hypovolemic shock), coma, seizures, urinary tract infection, kidney disease, heatstroke, hypernatremia, metabolic disease,[1] hypertension[2] |

| Causes | Loss of body water |

| Risk factors | Physical water scarcity, heatwaves, disease (most commonly from diseases that cause vomiting and/or diarrhea), exercise |

| Treatment | Drinking clean water |

| Medication | Saline |

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes.[3] It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake. This is usually due to excessive sweating, disease, or a lack of access to water. Mild dehydration can also be caused by immersion diuresis, which may increase risk of decompression sickness in divers.

Most people can tolerate a 3-4% decrease in total body water without difficulty or adverse health effects. A 5-8% decrease can cause fatigue and dizziness. Loss of over 10% of total body water can cause physical and mental deterioration, accompanied by severe thirst. Death occurs with a 15 and 25% loss of body water.[4] Mild dehydration usually resolves with oral rehydration, but severe cases may need intravenous fluids.

Dehydration can cause hypernatremia (high levels of sodium ions in the blood). This is distinct from hypovolemia (loss of blood volume, particularly blood plasma).

Chronic dehydration can cause kidney stones as well as the development of chronic kidney disease.[5][6]

- ^ a b "Dehydration - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ El-Sharkawy AM, Sahota O, Lobo DN (September 2015). "Acute and chronic effects of hydration status on health". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (Suppl 2): 97–109. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv038. PMID 26290295.

- ^ Mange K, Matsuura D, Cizman B, Soto H, Ziyadeh FN, Goldfarb S, et al. (November 1997). "Language guiding therapy: the case of dehydration versus volume depletion". Annals of Internal Medicine. 127 (9): 848–853. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00020. PMID 9382413. S2CID 29854540.

- ^ Ashcroft F, Life Without Water in Life at the Extremes. Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000, 134-138.

- ^ Seal AD, Suh HG, Jansen LT, Summers LG, Kavouras SA (2019). "Hydration and Health". In Pounis G (ed.). Analysis in Nutrition Research. Elsevier. pp. 299–319. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814556-2.00011-7. ISBN 978-0-12-814556-2.

- ^ Clark WF, Sontrop JM, Huang SH, Moist L, Bouby N, Bankir L (2016). "Hydration and Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: A Critical Review of the Evidence". American Journal of Nephrology. 43 (4): 281–292. doi:10.1159/000445959. PMID 27161565.