Back مخطط فاينمان Arabic Feynman diaqramı Azerbaijani Дыяграмы Фейнмана Byelorussian Диаграма на Файнман Bulgarian ফাইনম্যান চিত্র Bengali/Bangla Diagrama de Feynman Catalan Feynmanovy diagramy Czech Feynman-Diagramm German Διάγραμμα Φάινμαν Greek Diagrama de Feynman Spanish

|

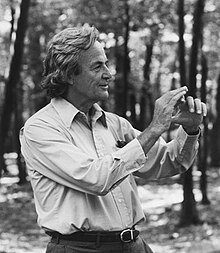

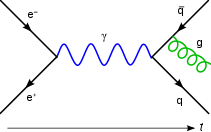

In theoretical physics, a Feynman diagram is a pictorial representation of the mathematical expressions describing the behavior and interaction of subatomic particles. The scheme is named after American physicist Richard Feynman, who introduced the diagrams in 1948.

The calculation of probability amplitudes in theoretical particle physics requires the use of large, complicated integrals over a large number of variables. Feynman diagrams instead represent these integrals graphically.

Feynman diagrams give a simple visualization of what would otherwise be an arcane and abstract formula. According to David Kaiser, "Since the middle of the 20th century, theoretical physicists have increasingly turned to this tool to help them undertake critical calculations. Feynman diagrams have revolutionized nearly every aspect of theoretical physics."[1]

While the diagrams apply primarily to quantum field theory, they can be used in other areas of physics, such as solid-state theory. Frank Wilczek wrote that the calculations that won him the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics "would have been literally unthinkable without Feynman diagrams, as would [Wilczek's] calculations that established a route to production and observation of the Higgs particle."[2]

A Feynman diagram is a graphical representation of a perturbative contribution to the transition amplitude or correlation function of a quantum mechanical or statistical field theory. Within the canonical formulation of quantum field theory, a Feynman diagram represents a term in the Wick's expansion of the perturbative S-matrix. Alternatively, the path integral formulation of quantum field theory represents the transition amplitude as a weighted sum of all possible histories of the system from the initial to the final state, in terms of either particles or fields. The transition amplitude is then given as the matrix element of the S-matrix between the initial and final states of the quantum system.

Feynman used Ernst Stueckelberg's interpretation of the positron as if it were an electron moving backward in time.[3] Thus, antiparticles are represented as moving backward along the time axis in Feynman diagrams.

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

- ^ Kaiser, David (2005). "Physics and Feynman's Diagrams" (PDF). American Scientist. 93 (2): 156. doi:10.1511/2005.52.957. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-05-27.

- ^ "Why Feynman Diagrams Are So Important". Quanta Magazine. 5 July 2016. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ Feynman, Richard (1949). "The Theory of Positrons". Physical Review. 76 (6): 749–759. Bibcode:1949PhRv...76..749F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.76.749. S2CID 120117564. Archived from the original on 2022-08-09. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

In this solution, the 'negative energy states' appear in a form which may be pictured (as by Stückelberg) in space-time as waves traveling away from the external potential backwards in time. Experimentally, such a wave corresponds to a positron approaching the potential and annihilating the electron.