Back Гоцэ Дэлчаў Byelorussian Гоце Делчев Bulgarian Gotse Deltchev Breton Goce Delčev BS Goce Delčev Czech Georgi Nikolow Deltschew German Γκότσε Ντέλτσεφ Greek Gotse Delchev Spanish Gotse Deltšev (vallankumouksellinen) Finnish Gotsé Deltchev French

Voivode Gotse Delchev | |

|---|---|

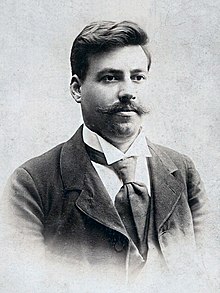

Portrait of Gotse Delchev in Sofia c. 1900 | |

| Native name | Гоце Делчев |

| Birth name | Georgi Nikolov Delchev |

| Other name(s) | Ahil (Archilles; nom de guerre) |

| Born | 4 February 1872 Kukush, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 4 May 1903 (aged 31) Banitsa, Ottoman Empire |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Buried | Banitsa (1903–1913) Xanthi (1913–1919) Plovdiv (1919–1923) Sofia (1923–1946) Church of the Ascension of Jesus, Skopje (since 1946) |

| Service | Bulgarian army Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee |

| Alma mater | Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki Military School of His Princely Highness |

| Other work | Teacher |

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Bulgarian: Георги Николов Делчев; Macedonian: Ѓорѓи Николов Делчев; 4 February 1872 – 4 May 1903), known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev (Гоце Делчев),[note 1] was a prominent Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji) and one of the most important leaders of what is commonly known as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO),[1] active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions, as well as in Bulgaria, at the turn of the 20th century.[2][3] Delchev was IMRO's foreign representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria.[4] As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC),[5] participating in the work of its governing body.[6] He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Born into a Bulgarian family in Kilkis,[7][8] then in the Salonika vilayet of the Ottoman Empire, in his youth he was inspired by the ideals of earlier Bulgarian revolutionaries such as Vasil Levski and Hristo Botev, who envisioned the creation of a Bulgarian republic of ethnic and religious equality, as part of an imagined Balkan Federation.[9] Delchev completed his secondary education in the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki and entered the Military School of His Princely Highness in Sofia, but at the final stage of his study, he was dismissed from it as an alleged socialist. Then he returned to Ottoman Macedonia and worked as a Bulgarian teacher,[10] and immediately became an activist of the newly-found revolutionary movement in 1894.[11]

Although considering himself to be an inheritor of the Bulgarian revolutionary traditions,[6] he opted for Macedonian autonomy.[12] Also for him, like for many Macedonian Bulgarians,[13] originating from an area with mixed population,[14] the idea of being 'Macedonian' acquired the importance of a certain native loyalty, that constructed a specific spirit of "local patriotism"[15][16] and "multi-ethnic regionalism".[17][18] He maintained the slogan promoted by William Ewart Gladstone, "Macedonia for the Macedonians", including all different nationalities inhabiting the area.[19][20][21] Delchev was also an adherent of incipient socialism.[22][23] His political agenda became the establishment through revolution of an autonomous Macedono-Adrianople supranational state into the framework of the Ottoman Empire, as a prelude to its incorporation within a future Balkan Federation.[24] Despite having been educated in the spirit of Bulgarian nationalism, he revised the Organization's statute, where the membership was allowed only for Bulgarians.[25] In this way he emphasized the importance of cooperation among all ethnic groups in the territories concerned in order to obtain political autonomy.[11]

Delchev is considered a national hero in Bulgaria and North Macedonia. Because his autonomist ideas have stimulated the subsequent development of Macedonian nationalism,[26] in the latter it is claimed he was an ethnic Macedonian revolutionary. Thus, Delchev's legacy has been disputed between both countries. Nevertheless, some researchers think that behind IMRO's idea of autonomy a reserve plan for eventual incorporation into Bulgaria was hidden.[27][28] Per some of his contemporaries and Bulgarian academic sources, Delchev supported Macedonia's incorporation into Bulgaria as another option too. Other researchers find the identity of Delchev and other IMRO figures to be open to different interpretations.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

- ^

- Danforth, Loring. "Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

IMRO was founded in 1893 in Thessaloníki; its early leaders included Damyan Gruev, Gotsé Delchev, and Yane Sandanski, men who had a Macedonian regional identity and a Bulgarian national identity.

- Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world. Princeton University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0691043566.

The political and military leaders of the Slavs of Macedonia at the turn of the century seem not to have heard Misirkov's call for a separate Macedonian national identity; they continued to identify themselves in a national sense as Bulgarian rather than Macedonians. (...) In spite of these political differences, both groups, including those who advocated an independent Macedonian state and opposed the idea of a greater Bulgaria, never seem to have doubted "the predominantly Bulgarian character of the population of Macedonia". (...) Even Gotse Delchev, the famous Macedonian revolutionary leader, whose nom de guerre was Ahil (Achilles), refers to "the Slavs of Macedonia as 'Bulgarians' in an offhanded manner without seeming to indicate that such a designation was a point of contention" (Perry 1988:23). In his correspondence Gotse Delchev often states clearly and simply, "We are Bulgarians" (Mac Dermott 1978:273).

- Perry, Duncan M. (1988). The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780822308133.

- Victor Roudometof (2002). Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 79. ISBN 0275976483.

- İlkay Yılmaz (2023). Ottoman Passports: Security and Geographic Mobility, 1876-1908. Syracuse University Press. p. 265. ISBN 9780815656937.

- Danforth, Loring. "Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Keith Brown (2018). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation,. Princeton University Press. p. 174. ISBN 0691188432.

- ^ Hugh Seton-Watson (1981). The Making of a New Europe: R.W. Seton-Watson and the Last Years of Austria-Hungary. Methuen. p. 71. ISBN 0416747302.

- ^ Angelos Chotzidis; Anna Panagiōtopoulou; Vasilis Gounaris, eds. (1993). The Events of 1903 in Macedonia as Presented in European Diplomatic Correspondence. p. 60. ISBN 9608530334.

- ^ Laura Beth Sherman (1980). Fires on the Mountain: The Macedonian Revolutionary Movement and the Kidnapping of Ellen Stone. East European monographs. p. 18. ISBN 0914710559.

From 1899 to 1901, the supreme committee provided subsidies to IMRO's central committee, allowances for Delchev and Petrov in Sofia, and weapons for bands sent to the interior. Delchev and Petrov were elected full members of the supreme committee.

- ^ a b Duncan M. Perry (1988). The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903. Duke University Press. pp. 39–40, 82–83, 120. ISBN 0822308134.

- ^ Susan K. Kinnell (1989). People in World History, Volume 1; An Index to Biographies in History Journals and Dissertations Covering All Countries of the World Except Canada and the U.S. ABC-CLIO. p. 157. ISBN 0874365503.

- ^ Delchev was born into a family of Bulgarian Uniates, who later switched to Bulgarian Еxarchists. For more see: Светозар Елдъров, Униатството в съдбата на България: очерци из историята на българската католическа църква от източен обред, Абагар, 1994, ISBN 9548614014, стр. 15.

- ^ Charles Jelavich (1986). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804-1920. University of Washington Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 0295803606.

- ^ Hugh Poulton (2000). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 53–55, 117. ISBN 1850655340.

- ^ a b Raymond Detrez (2010). The A to Z of Bulgaria. Scarecrow Press. p. 135. ISBN 0810872021.

- ^ Maria Todorova (2009). Bones of Contention: The Living Archive of Vasil Levski and the Making of Bulgaria's National Hero. Central European University Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 9639776246.

- ^ Denis Š. Ljuljanović (2023). Imagining Macedonia in the Age of Empire: State Policies, Networks and Violence (1878–1912). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 219. ISBN 9783643914460.

- ^ Wes Johnson (2007). Balkan inferno: betrayal, war and intervention, 1990-2005. Enigma Books. p. 80. ISBN 1929631634.

The French referred to 'Macedoine' as an area of mixed races — and named a salad after it. One doubts that Gotse Delchev approved of this descriptive, but trivial approach.

- ^ Chris Kostov (2010). Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996. Peter Lang. p. 112. ISBN 3034301960.

The Bulgarian historians, such as Veselin Angelov, Nikola Achkov and Kosta Tzarnushanov continue to publish their research backed with many primary sources to prove that the term 'Macedonian' when applied to Slavs has always meant only a regional identity of the Bulgarians.

- ^ Athanasios Moulakis (2010). "The Controversial Ethnogenesis of Macedonia". European Political Science: 497. ISSN 1680-4333.

Gotse Delchev, may, as Macedonian historians claim, have 'objectively' served the cause of Macedonian independence, but in his letters he called himself a Bulgarian. In other words it is not clear that the sense of Slavic Macedonian identity at the time of Delchev was in general developed.

- ^ Klaus Roth; Ulf Brunnbauer (2009). Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 133. ISBN 3825813878.

The article in Reformi states that some Slavic Macedonian intellectuals felt loyalty to Macedonia as a region or territory without claiming any specifically Macedonian ethnicity. The primary aim of multi-ethnic Macedonian regionalism was an alliance of Greeks and Slavs (read: Bulgarians) against Ottoman rule.

- ^ Klaus Roth; Ulf Brunnbauer (2009). Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 136. ISBN 3825813878.

The Bulgarian loyalties of IMRO's leadership, however, coexisted with the desire for multi-ethnic Macedonia to enjoy administrative autonomy. When Delchev was elected to IMRO's Central Committee in 1896, he opened membership in IMRO to all inhabitants of European Turkey since the goal was to assemble all dissatisfied elements in Macedonia and Adrianople regions regardless of ethnicity or religion in order to win through revolution full autonomy for both regions.

- ^ Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3038-5., p. 56

- ^ Tchavdar Marinov (2009). "We, the Macedonians, The Paths of Macedonian Supra-Nationalism (1878–1912)". In Diana Mishkova (ed.). We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe. Central European University Press. pp. 117–120. ISBN 9639776289.

- ^ Anastasia Karakasidou (2009). Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990. University of Chicago Press. p. 282. ISBN 0226424995.

- ^ Peter Vasiliadis (1989). Whose are you? identity and ethnicity among the Toronto Macedonians. AMS Press. p. 77. ISBN 0404194680. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ The earliest document which talks about the autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace into the Ottoman Empire is the resolution of the First congress of the Supreme Macedonian Committee held in Sofia in 1895. От София до Костур -освободителните борби на българите от Македония в спомени на дейци от Върховния македоно-одрински комитет, Ива Бурилкова, Цочо Билярски - съставители, ISBN 9549983234, Синева, 2003, стр. 6.

- ^ Opfer, Björn (2005). Im Schatten des Krieges: Besatzung oder Anschluss - Befreiung oder Unterdrückung? ; eine komparative Untersuchung über die bulgarische Herrschaft in Vardar-Makedonien 1915-1918 und 1941-1944. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-7997-6., pp. 27-28

- ^ Laura Beth Sherman (1980). Fires on the mountain: the Macedonian revolutionary movement and the kidnapping of Ellen Stone, Volume 62. East European Monographs. p. 10. ISBN 0914710559.

- ^ Roumen Dontchev Daskalov; Tchavdar Marinov (2013). Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. pp. 300–303. ISBN 900425076X.

- ^ İpek Yosmaoğlu (2013). Blood Ties: Religion, Violence and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908,. Cornell University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0801469791.

- ^ Dimitris Livanios (2008). The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939-1949. OUP Oxford. p. 17. ISBN 0191528722.