Back Turkse bad Afrikaans حمام عام Arabic حمام عمومى ARZ Hamam Azerbaijani Һамам Bashkir Хамам Bulgarian Hamam BS Bany turc Catalan Turecká lázeň Czech Хаммам CV

A hammam (Arabic: حمّام, romanized: ḥammām), also often called a Turkish bath by Westerners,[1] is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited from the model of the Roman thermae.[2][3][4] Muslim bathhouses or hammams were historically found across the Middle East, North Africa, al-Andalus (Islamic Iberia, i.e. Spain and Portugal), Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and in Southeastern Europe under Ottoman rule.

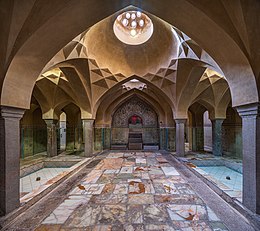

In Islamic cultures the significance of the hammam was both religious and civic: it provided for the needs of ritual ablutions but also provided for general hygiene in an era before private plumbing and served other social functions such as offering a gendered meeting place for men and for women.[2][3][5] Archeological remains attest to the existence of bathhouses in the Islamic world as early as the Umayyad period (7th–8th centuries) and their importance has persisted up to modern times.[5][2] Their architecture evolved from the layout of Roman and Greek bathhouses and featured a regular sequence of rooms: an undressing room, a cold room, a warm room, and a hot room. Heat was produced by furnaces which provided hot water and steam, while smoke and hot air was channeled through conduits under the floor.[3][5][4]

In a modern hammam visitors undress themselves, while retaining some sort of modesty garment or loincloth, and proceed into progressively hotter rooms, inducing perspiration. They are then usually washed by male or female staff (matching the gender of the visitor) with the use of soap and vigorous rubbing, before ending by washing themselves in warm water.[5] Unlike in Roman or Greek baths, bathers usually wash themselves with running water instead of immersing themselves in standing water since this is a requirement of Islam,[3] though immersion in a pool used to be customary in the hammams of some regions such as Iran.[6] While hammams everywhere generally operate in fairly similar ways, there are some regional differences both in usage and architecture.[5]

- ^ Peteet, Julie (2024). The Hammam through Time and Space. Gender, Culture, and Politics in the Middle East. Syracuse University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780815638322.

- ^ a b c M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Bath". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Sibleywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

:052was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:20was invoked but never defined (see the help page).