Back هارلان فيسك ستون Arabic هارلان فيسك ستون ARZ هارلان اف. ایستون AZB Harlan Fiske Stone Czech Harlan Fiske Stone German هارلان اف استون Persian Harlan Fiske Stone French הרלן סטון HE Harlan Fiske Stone ID Harlan Fiske Stone Italian

Harlan F. Stone | |

|---|---|

| |

| 12th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office July 3, 1941 – April 22, 1946 | |

| Nominated by | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Charles Evans Hughes |

| Succeeded by | Fred M. Vinson |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office March 2, 1925 – July 3, 1941 | |

| Nominated by | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Joseph McKenna |

| Succeeded by | Robert H. Jackson |

| 52nd United States Attorney General | |

| In office April 7, 1924 – March 1, 1925 | |

| President | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Harry M. Daugherty |

| Succeeded by | John G. Sargent |

| 4th Dean of Columbia Law School | |

| In office 1910–1923 | |

| Preceded by | George Washington Kirchwey |

| Succeeded by | Young Berryman Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Harlan Fiske Stone October 11, 1872 Chesterfield, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | April 22, 1946 (aged 73) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Rock Creek Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Agnes Harvey (m. 1899) |

| Children | |

| Education | Massachusetts Agricultural College (expelled) Amherst College (BS) Columbia University (LLB) |

| Signature | |

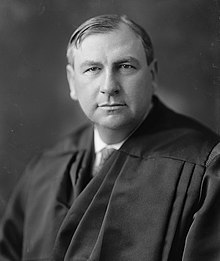

Harlan Fiske Stone (October 11, 1872 – April 22, 1946) was an American attorney who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1925 to 1941 and then as the 12th chief justice of the United States from 1941 until his death in 1946. He also served as the U.S. Attorney General from 1924 to 1925 under President Calvin Coolidge, with whom he had attended Amherst College as a young man. His most famous dictum was that "Courts are not the only agency of government that must be assumed to have capacity to govern."[1]

Raised in Western Massachusetts,[2] Stone practiced law in New York City after graduating from Columbia Law School. He became the Dean of Columbia Law School and a partner with Sullivan & Cromwell. During World War I, he served on the U.S. Department of War's Board of Inquiry, which evaluated the sincerity of conscientious objectors. In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Stone as the Attorney General. Stone sought to reform the U.S. Department of Justice in the aftermath of several scandals that occurred during the administration of President Warren G. Harding. He also pursued several antitrust cases against large corporations.

In 1925, Coolidge nominated Stone to the Supreme Court to succeed retiring Associate Justice Joseph McKenna, and Stone won U.S. Senate confirmation with little opposition. On the Taft Court, Stone joined with Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis Brandeis in calling for judicial restraint and deference to the legislative will. On the Hughes Court, Stone and Justices Brandeis and Benjamin N. Cardozo formed a liberal bloc called the Three Musketeers that generally voted to uphold the constitutionality of the New Deal. His majority opinions in United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941) and United States v. Carolene Products Co. (1938) were influential in shaping standards of judicial scrutiny.

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt nominated Stone to succeed the retiring Charles Evans Hughes as Chief Justice, and the Senate quickly confirmed Stone. The Stone Court presided over several cases during World War II, and Stone's majority opinion in Ex parte Quirin upheld the jurisdiction of a U.S. military tribunal over the trial of eight German saboteurs. His majority opinion in International Shoe Co. v. Washington (1945) was influential with regards to personal jurisdiction. Stone was the chief justice in Korematsu v. United States (1944), ruling the exclusion of Japanese Americans into internment camps as constitutional. Stone served as Chief Justice until his death in 1946. He had one of the shortest terms of any chief justice, and was the first chief justice not to have served in elected office.

- ^ Frank, John P.; Mason, Alpheus Thomas (1957). "Harlan Fiske Stone: An Estimate". Stanford Law Review. 9 (3): 621–632. doi:10.2307/1226615. JSTOR 1226615. Frank cites "United States v. Butler, 297 U.S. 1, 87 (1936) (dissenting opinion)" Archived 2013-07-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Burlingham, Charles (1946). "Harlan Fiske Stone". American Bar Association Journal. 32 (6). American Bar Association: 322–324. JSTOR 25715606.