Back الآثار الصحية للتدخين Arabic Здравни ефекти от тютюнопушенето Bulgarian স্বাস্থ্যের উপর তামাকের প্রভাব Bengali/Bangla کاریگەرییە تەندروستییەکانی تووتن CKB Zdravotní rizika kouření tabáku Czech Efectos del tabaco en la salud Spanish Tabakoaren eragina osasunean Basque تأثیرات تنباکو بر سلامت انسان Persian Tupakoinnin terveysvaikutukset Finnish Effets du tabac sur la santé French

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

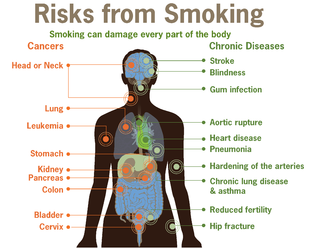

Tobacco products, especially when smoked or used orally, have serious negative effects on human health.[1][2] Smoking and smokeless tobacco use are the single greatest causes of preventable death globally.[3] Half of tobacco users die from complications related to such use.[4][5] Current smokers are estimated to die an average of 10 years earlier than non-smokers.[6] The World Health Organization estimates that, in total, about 8 million people die from tobacco-related causes, including 1.3 million non-smokers due to secondhand smoke.[7] It is further estimated to have caused 100 million deaths in the 20th century.[4]

Tobacco smoke contains over 70 chemicals, known as carcinogens, that cause cancer.[4][8] It also contains nicotine, a highly addictive psychoactive drug. When tobacco is smoked, the nicotine causes physical and psychological dependency. Cigarettes sold in least developed countries have higher tar content and are less likely to be filtered, increasing vulnerability to tobacco smoking–related diseases in these regions.[9]

Tobacco use most commonly leads to diseases affecting the heart, liver, and lungs. Smoking is a major risk factor for several conditions, namely pneumonia, heart attacks, strokes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—including emphysema and chronic bronchitis—and multiple cancers (particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer). It is also responsible for peripheral arterial disease and high blood pressure. The effects vary depending on how frequently and for how many years a person smokes. Smoking earlier in life and smoking cigarettes higher in tar increase the risk of these diseases. Additionally, environmental tobacco smoke, known as secondhand smoke, has manifested harmful health effects in people of all ages.[10] Tobacco use is also a significant risk factor in miscarriages among pregnant smokers. It contributes to a number of other health problems for the fetus, such as premature birth and low birth weight, and increases the chance of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) by 1.4 to 3 times.[11] The incidence of erectile dysfunction is approximately 85 percent higher in male smokers compared to non-smokers.[12][13]

Many countries have taken measures to control the consumption of tobacco by restricting its usage and sales. They have printed warning messages on packaging. Moreover, smoke-free laws that ban smoking in public places like workplaces, theaters, bars, and restaurants have been enacted to reduce exposure to secondhand smoke.[4] Tobacco taxes inflating the price of tobacco products have also been imposed.[4]

In the late 1700s and the 1800s, the idea that tobacco use caused certain diseases, including mouth cancers, was initially accepted by the medical community.[14] In the 1880s, automation dramatically reduced the cost of cigarettes, cigarette companies greatly increased their marketing, and use expanded.[15][16] From the 1890s onwards, associations of tobacco use with cancers and vascular disease were regularly reported. By the 1930s, multiple researchers concluded that tobacco use caused cancer and that tobacco users lived substantially shorter lives.[17][18] Further studies were published in Nazi Germany in 1939 and 1943, and one in the Netherlands in 1948. However, widespread attention was first drawn in 1950 by researchers from the United States and the United Kingdom, but their research was widely criticized. Follow-up studies in the early 1950s found that smokers died faster and were more likely to die of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease.[14] These results were accepted in the medical community and publicized among the general public in the mid-1960s.[14]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

WHOPrevalenceAdultsAge15was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

WHOMayoReportwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2008 : The MPOWER Package (PDF). World Health Organization. 2008. pp. 6, 8, 20. ISBN 9789240683112. OCLC 476167599. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ a b c d e "Tobacco Fact sheet N°339". May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ Doll, Richard; Peto, Richard; Boreham, Jillian; Sutherland, Isabelle (2004-06-24). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ. 328 (7455): 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

- ^ Banks, Emily; Joshy, Grace; Weber, Marianne F; Liu, Bette; Grenfell, Robert; Egger, Sam; Paige, Ellie; Lopez, Alan D; Sitas, Freddy; Beral, Valerie (2015-02-24). "Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence". BMC Medicine. 13 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0281-z. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 4339244. PMID 25857449.

- ^ "Tobacco". www.who.int. 2024-07-31. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ "Harmful Chemicals in Tobacco Products". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Nichter M, Cartwright E (1991). "Saving the Children for the Tobacco Industry". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 5 (3): 236–56. doi:10.1525/maq.1991.5.3.02a00040. JSTOR 648675.

- ^ Vainio H (June 1987). "Is passive smoking increasing cancer risk?". Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 13 (3): 193–6. doi:10.5271/sjweh.2066. PMID 3303311.

- ^ "The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General" (PDF). Atlanta, U.S.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. 2006. p. 93. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid15924009was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Korenman SG (2004). "Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction". Endocrine. 23 (2–3): 87–91. doi:10.1385/ENDO:23:2-3:087. PMID 15146084. S2CID 29133230.

- ^ a b c Doll R (June 1998). "Uncovering the effects of smoking: historical perspective" (PDF). Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 7 (2): 87–117. doi:10.1177/096228029800700202. PMID 9654637. S2CID 154707. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ Alston LJ, Dupré R, Nonnenmacher T (2002). "Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada". Explorations in Economic History. 39 (4): 425–445. doi:10.1016/S0014-4983(02)00005-0.

- ^ James R (2009-06-15). "A Brief History Of Cigarette Advertising". TIME. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ Haustein KO (2004). "Fritz Lickint (1898–1960) – Ein Leben als Aufklärer über die Gefahren des Tabaks". Suchtmed (in German). 6 (3): 249–255. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014.

- ^ Proctor RN (February 2001). "Commentary: Schairer and Schöniger's forgotten tobacco epidemiology and the Nazi quest for racial purity". International Journal of Epidemiology. 30 (1): 31–4. doi:10.1093/ije/30.1.31. PMID 11171846.