Back Шестоднев Bulgarian Hexaemeron German Hexamerón Spanish Heksaemeron Polish Hexamerão Portuguese Шестоднев Russian Шестоднев Ukrainian

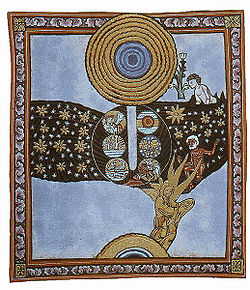

The term Hexaemeron (Greek: Ἡ Ἑξαήμερος Δημιουργία Hē Hexaēmeros Dēmiourgia), literally "six days," is used in one of two senses. In one sense, it refers to the Genesis creation narrative spanning Genesis 1:1–2:3:[1] corresponding to the creation of the light (day 1); the sky (day 2); the earth, seas, and vegetation (day 3); the sun and moon (day 4); animals of the air and sea (day 5); and land animals and humans (day 6). God then rests from his work on the seventh day of creation, the Sabbath.[2]

In a second sense, the Genesis creation narrative inspired a didactic[3] genre of Jewish and Christian literature known as the Hexaemeral literature.[4] Literary treatments in this genre are called Hexaemeron.[2] This literature was dedicated to the composition of commentaries, homilies, and treatises concerned with the exegesis of the biblical creation narrative through ancient and medieval times and with expounding the meaning of the six days as well as the origins of the world.[5] The first Christian example of this genre was the Hexaemeron of Basil of Caesarea, and many other works went on to be written from authors including Augustine of Hippo, Jacob of Serugh, Jacob of Edessa, Bonaventure, and so on. These treatises would become popular and often cover a wide variety of topics, including cosmology, science, theology, theological anthropology, and God's nature.[6] The word can also sometimes denote more passing or incidental descriptions or discussions on the six days of creation,[7] such as in the brief occurrences that appear in Quranic cosmology.[8]

The Church Fathers wrote many Hexaemeron and a diversity of opinions existed on a broad range of subjects. Two general modes of interpretation existed, corresponding to the literal form of interpretation, represented by the tradition of the School of Antioch (one example being in John Chrysostom), and another represented by an allegorical mode of interpretation, represented by the tradition of the School of Alexandria (examples being Origen and Augustine).[9] Outside of this categorization, however, individuals in each school would not necessarily deny the validity of the alternative perspective. Despite the differences, consensus existed on a number of subjects among these interpreters, including in their belief in God's primacy as the Creator; the occurrence of creation through the act of the divine Word (Christ) and the Spirit; on the created and not eternal nature of the world, God's creation of both the spiritual and material realms (including the human body and soul); and the continuing providential care over the creation by God. The Church Fathers primarily focused on the first two chapters of Genesis, as well as a few essential statements in the New Testament (John 1:1–4; 1 Corinthians 8:6).[10]

- ^ Brown 2019, p. 12.

- ^ a b Sarna 1966, p. 1–2.

- ^ Christopher Kendrick, Milton: A Study in Ideology and Form (1986), p. 125.

- ^ Gasper 2024.

- ^ Brown 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Katsos 2023, p. 15–16.

- ^ Robbins 1912, p. 1–2.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 128.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 172–173.

- ^ De Beer 2015.