Back تفاوت الدخل في الولايات المتحدة Arabic ABŞ-də gəlir bərabərsizliyi Azerbaijani Desigualdad de ingreso en Estados Unidos Spanish Nierówności dochodowe w Stanach Zjednoczonych Polish Concentração de renda nos Estados Unidos Portuguese Income inequality in the United States SIMPLE

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Income in the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

|

Income inequality has fluctuated considerably in the United States since measurements began around 1915, moving in an arc between peaks in the 1920s and 2000s, with a 30-year period of relatively lower inequality between 1950 and 1980.

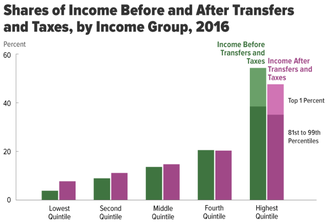

The U.S. has the highest level of income inequality among its (post-)industrialized peers.[1] When measured for all households, U.S. income inequality is comparable to other developed countries before taxes and transfers, but is among the highest after taxes and transfers, meaning the U.S. shifts relatively less income from higher income households to lower income households. In 2016, average market income was $15,600 for the lowest quintile and $280,300 for the highest quintile. The degree of inequality accelerated within the top quintile, with the top 1% at $1.8 million, approximately 30 times the $59,300 income of the middle quintile.[2]

The economic and political impacts of inequality may include slower GDP growth, reduced income mobility, higher poverty rates, greater usage of household debt leading to increased risk of financial crises, and political polarization.[3][4] Causes of inequality may include executive compensation increasing relative to the average worker, financialization, greater industry concentration, lower unionization rates, lower effective tax rates on higher incomes, and technology changes that reward higher educational attainment.[5]

Measurement is debated, as inequality measures vary significantly, for example, across datasets[6][7] or whether the measurement is taken based on cash compensation (market income) or after taxes and transfer payments. The Gini coefficient is a widely accepted statistic that applies comparisons across jurisdictions, with a zero indicating perfect equality and 1 indicating maximum inequality. Further, various public and private data sets measure those incomes, e.g., from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO),[2] the Internal Revenue Service, and Census.[8] According to the Census Bureau, income inequality reached then record levels in 2018, with a Gini of 0.485,[9] Since then the Census Bureau have given values of 0.488 in 2020 and 0.494 in 2021, per pre-tax money income.[10]

U.S. tax and transfer policies are progressive and therefore reduce effective income inequality, as rates of tax generally increase as taxable income increases. As a group, the lowest earning workers, especially those with dependents, pay no income taxes and may actually receive a small subsidy from the federal government (from child credits and the Earned Income Tax Credit).[11] The 2016 U.S. Gini coefficient was .59 based on market income, but was reduced to .42 after taxes and transfers, according to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) figures. The top 1% share of market income rose from 9.6% in 1979 to a peak of 20.7% in 2007, before falling to 17.5% by 2016. After taxes and transfers, these figures were 7.4%, 16.6%, and 12.5%, respectively.[2]

- ^ United Press International (UPI), June 22, 2018, "U.N. Report: With 40M in Poverty, U.S. Most Unequal Developed Nation"

- ^ a b c "The Distribution of Household Income, 2016". www.cbo.gov. Congressional Budget Office. July 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Krueger, Alan (January 12, 2012). "Chairman Alan Krueger Discusses the Rise and Consequences of Inequality at the Center for American Progress". whitehouse.gov – via National Archives.

- ^ Stewart, Alexander J.; McCarty, Nolan; Bryson, Joanna J. (2020). "Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline". Science Advances. 6 (50): eabd4201. arXiv:1807.11477. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.4201S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd4201. PMC 7732181. PMID 33310855. S2CID 216144890.

- ^ Porter, Eduardo (November 12, 2013). "Rethinking the Rise of Inequality". NYT.

- ^ "Why the gap between worker pay and productivity might be a myth". July 23, 2015.

- ^ Rose, Stephen J. (December 2018). "Measuring Income Inequality in the US: Methodological Issues" (PDF). Urban Institute. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States" (PDF). NBER. December 1, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Telford (September 26, 2019). "Income inequality in America is the highest it's been since census started tracking it, data shows". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ Semega, Jessica; Kollar, Melissa (September 13, 2022). "2021 Income Inequality Increased for First Time Since 2011". census.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2010". The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO). December 4, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2014.