Back Biblioteek van Alexandrië Afrikaans Agwut Ikpa Alikisendira ANN مكتبة الإسكندرية Arabic مكتبة اسكندريه ARZ Biblioteca d'Alexandría AST İsgəndəriyyə kitabxanası Azerbaijani Александрыйская бібліятэка Byelorussian Александрийска библиотека Bulgarian আলেকজান্দ্রিয়ার প্রাচীন গ্রন্থাগার Bengali/Bangla Levraoueg Aleksandria Breton

| Library of Alexandria | |

|---|---|

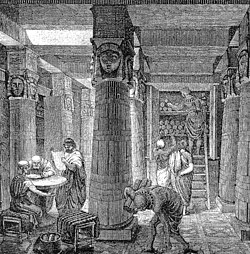

Nineteenth-century artistic rendering of the Library of Alexandria by the German artist O. Von Corven, based partially on the archaeological evidence available at that time[1] | |

| |

| Location | Alexandria, Egypt, Ptolemaic Kingdom |

| Type | National library |

| Established | Possibly during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC)[2][3] |

| Collection | |

| Items collected | Any written works[4][5] |

| Size | Estimates vary; somewhere between 40,000 and 400,000 scrolls,[6] perhaps equivalent to roughly 100,000 books[7] |

| Other information | |

| Employees | Estimated to have employed over 100 scholars at its height[8][9] |

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, the nine goddesses of the arts.[10] The idea of a universal library in Alexandria may have been proposed by Demetrius of Phalerum, an exiled Athenian statesman living in Alexandria, to Ptolemy I Soter, who may have established plans for the Library, but the Library itself was probably not built until the reign of his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The Library quickly acquired many papyrus scrolls, owing largely to the Ptolemaic kings' aggressive and well-funded policies for procuring texts. It is unknown precisely how many scrolls were housed at any given time, but estimates range from 40,000 to 400,000 at its height.

Alexandria came to be regarded as the capital of knowledge and learning, in part because of the Great Library.[11] Many important and influential scholars worked at the Library during the third and second centuries BC, including: Zenodotus of Ephesus, who worked towards standardizing the works of Homer; Callimachus, who wrote the Pinakes, sometimes considered the world's first library catalog; Apollonius of Rhodes, who composed the epic poem the Argonautica; Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who calculated the circumference of the earth within a few hundred kilometers of accuracy; Hero of Alexandria, who invented the first recorded steam engine; Aristophanes of Byzantium, who invented the system of Greek diacritics and was the first to divide poetic texts into lines; and Aristarchus of Samothrace, who produced the definitive texts of the Homeric poems as well as extensive commentaries on them. During the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, a daughter library was established in the Serapeum, a temple to the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis.

The influence of the Library declined gradually over the course of several centuries. This decline began with the purging of intellectuals from Alexandria in 145 BC during the reign of Ptolemy VIII Physcon, which resulted in Aristarchus of Samothrace, the head librarian, resigning and exiling himself to Cyprus. Many other scholars, including Dionysius Thrax and Apollodorus of Athens, fled to other cities, where they continued teaching and conducting scholarship. The Library, or part of its collection, was accidentally burned by Julius Caesar during his civil war in 48 BC, but it is unclear how much was actually destroyed and it seems to have either survived or been rebuilt shortly thereafter. The geographer Strabo mentions having visited the Mouseion in around 20 BC, and the prodigious scholarly output of Didymus Chalcenterus in Alexandria from this period indicates that he had access to at least some of the Library's resources.

The Library dwindled during the Roman period, from a lack of funding and support. Its membership appears to have ceased by the 260s AD. Between 270 and 275 AD, Alexandria saw a Palmyrene invasion and an imperial counterattack that probably destroyed whatever remained of the Library, if it still existed. The daughter library in the Serapeum may have survived after the main Library's destruction. The Serapeum was vandalized and demolished in 391 AD under a decree issued by bishop Theophilus of Alexandria, but it does not seem to have housed books at the time, and was mainly used as a gathering place for Neoplatonist philosophers following the teachings of Iamblichus.

- ^ Garland 2008, p. 61.

- ^ Tracy 2000, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Phillips 2010.

- ^ MacLeod 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Casson 2001, p. 35.

- ^ Wiegand & Davis 2015, p. 20.

- ^ Garland 2008, p. 60.

- ^ Haughton 2011.

- ^ MacLeod 2000, p. 5.

- ^ Murray, S. A., (2009). The library: An illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, p. 17

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The library: an illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-61608-453-0. OCLC 277203534.