Back إعدام دون محاكمة في الولايات المتحدة Arabic Linchamiento en Estados Unidos Spanish لینچکردن در ایالات متحده آمریکا Persian Hukuman mati tanpa pengadilan di Amerika Serikat ID Linciaggio negli Stati Uniti d'America Italian Linchamentos nos Estados Unidos Portuguese Lynching in the United States SIMPLE

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s, slowed during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and continued until 1981. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimized ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states.[3] In 1891, the largest single mass lynching (11) in American history was perpetrated in New Orleans against Italian immigrants.[4][5]

Lynchings followed African Americans with the Great Migration (c. 1916–1970) out of the American South, and were often perpetrated to enforce white supremacy and intimidate ethnic minorities along with other acts of racial terrorism.[6] A significant number of lynching victims were accused of murder or attempted murder. Rape, attempted rape, or other forms of sexual assault were the second most common accusation; these accusations were often used as a pretext for lynching African Americans who were accused of violating Jim Crow era etiquette or engaged in economic competition with Whites. One study found that there were "4,467 total victims of lynching from 1883 to 1941. Of these victims, 4,027 were men, 99 were women, and 341 were of unidentified gender (although likely male); 3,265 were Black, 1,082 were white, 71 were Mexican or of Mexican descent, 38 were American Indian, 10 were Chinese, and 1 was Japanese."[7]

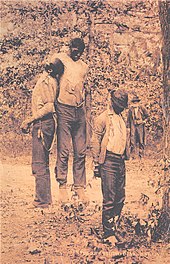

A common perception of lynchings in the U.S. is that they were only hangings, due to the public visibility of the location, which made it easier for photographers to photograph the victims. Some lynchings were professionally photographed and then the photos were sold as postcards, which became popular souvenirs in parts of the United States. Lynching victims were also killed in a variety of other ways: being shot, burned alive, thrown off a bridge, dragged behind a car, etc. Occasionally, the body parts of the victims were removed and sold as souvenirs. Lynchings were not always fatal; "mock" lynchings, which involved putting a rope around the neck of someone who was suspected of concealing information, was sometimes used to compel people to make "confessions". Lynch mobs varied in size from just a few to thousands.

Lynching steadily increased after the Civil War, peaking in 1892. Lynchings remained common into the early 1900s, accelerating with the emergence of the Second Ku Klux Klan. Lynchings declined considerably by the time of the Great Depression. The 1955 lynching of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy, galvanized the civil rights movement and marked the last classical lynching (as recorded by the Tuskegee Institute). The overwhelming majority of lynching perpetrators never faced justice. White supremacy and all-white juries ensured that perpetrators, even if tried, would not be convicted. Campaigns against lynching gained momentum in the early 20th century, championed by groups such as the NAACP. Some 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress between the end of the Civil War and the Civil Rights movement, but none passed. Finally, in 2022, 67 years after Emmett Till's killing and the end of the lynching era, the United States Congress passed anti-lynching legislation in the form of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act.

- ^ https://archive.tuskegee.edu/repository/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lynchings-Stats-Year-Dates-Causes.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Cartersville Lynchings". ValdostaMuseum.com. Lowndes County Historical Society Museum. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ejiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wood, Amy Louise (2009). Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874–1947. North Carolina University Press. ISBN 9780807878118. OCLC 701719807.

- ^ "Commemorating LA's Chinese Massacre, possibly the worst lynching in US history", Robert Petersen, Off-Ramp, South Carolina Public Radio, 21 October 2016

- ^ "History of Lynching in America". NAACP. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Seguin, Charles; Rigby, David (2019). "National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941". Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World. 5. doi:10.1177/2378023119841780. ISSN 2378-0231. S2CID 164388036.