Back مندالة (نموذج سياسي) Arabic মণ্ডল (রাজনৈতিক গঠনতন্ত্র) Bengali/Bangla Mandala (model polític) Catalan Mandalový systém Czech Mandala (politisches Modell) German मण्डल (राजनैतिक मॉडल) Hindi Mandala (sejarah Asia Tenggara) ID Mandala (politica) Italian マンダラ論 Japanese មណ្ឌល (គំរូនយោបាយ) Cambodian

| Part of a series on |

| Political and legal anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

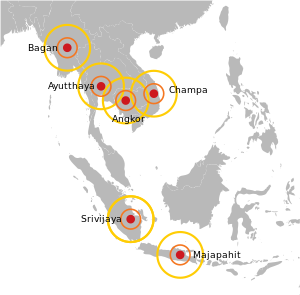

Maṇḍala is a Sanskrit word meaning 'circle'. The mandala is a model for describing the patterns of diffuse political power distributed among Mueang or Kedatuan (principalities) in medieval Southeast Asian history, when local power was more important than the central leadership. The concept of the mandala balances modern tendencies to look for unified political power, e.g. the power of large kingdoms and nation states of later history – an inadvertent byproduct of 15th century advances in map-making technologies.[further explanation needed][1][2] In the words of O. W. Wolters who further explored the idea in 1982:

The map of earlier Southeast Asia which evolved from the prehistoric networks of small settlements and reveals itself in historical records was a patchwork of often overlapping mandalas.[3]

It is employed to denote traditional Southeast Asian political formations, such as federation of kingdoms or vassalized polity under a center of domination. It was adopted by 20th century European historians from ancient Indian political discourse as a means of avoiding the term "state" in the conventional sense. Not only did Southeast Asian polities, except Vietnam, not conform to Chinese and European views of a territorially defined state with fixed borders and a bureaucratic apparatus, but they diverged considerably in the opposite direction: the polity was defined by its centre rather than its boundaries, and it could be composed of numerous other tributary polities without undergoing administrative integration.[4]

In some ways similar to the feudal system of Europe, states were linked in suzerain–tributary relationships.

- ^ "How Maps Made the World". Wilson Quarterly. Summer 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

Source: 'Mapping the Sovereign State: Technology, Authority, and Systemic Change' by Jordan Branch, in International Organization, Volume 65, Issue 1, Winter 2011

- ^ Branch, Jordan Nathaniel; Steven Weber (2011). Mapping the Sovereign State: Cartographic Technology, Political Authority, and Systemic Change (PhD thesis). University of California, Berkeley. pp. 1–36. doi:10.1017/S0020818310000299. Publication Number 3469226.

Abstract: How did modern territorial states come to replace earlier forms of organization, defined by a wide variety of territorial and non-territorial forms of authority? Answering this question can help to explain both where our international political system came from and where it might be going ...

The idea was originally proposed by Stanley J. Tambiah, a professor of anthropology, in a 1977 article entitled "The Galactic Polity: The structure of Political Kingdoms in Southeast Asia." - ^ O.W. Wolters, 1999, p. 27

- ^ Dellios, Rosita (2003-01-01). "Mandala: from sacred origins to sovereign affairs in traditional Southeast Asia". Bond University Australia.