Back Monofileties Afrikaans Monofilia (filochenetica) AN أحادي النمط الخلوي Arabic Monofiliya Azerbaijani Monofiletska evolucija BS Monofiletisme Catalan Monofyletismus Czech Монофили CV Monofyletisk gruppe Danish Monofiletika Esperanto

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

- the grouping contains its own most recent common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population), i.e. excludes non-descendants of that common ancestor

- the grouping contains all the descendants of that common ancestor, without exception

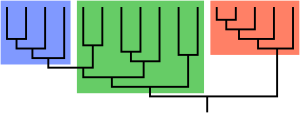

Monophyly is contrasted with paraphyly and polyphyly as shown in the second diagram. A paraphyletic grouping meets 1. but not 2., thus consisting of the descendants of a common ancestor, excepting one or more monophyletic subgroups. A polyphyletic grouping meets neither criterion, and instead serves to characterize convergent relationships of biological features rather than genetic relationships – for example, night-active primates, fruit trees, or aquatic insects. As such, these characteristic features of a polyphyletic grouping are not inherited from a common ancestor, but evolved independently.

Monophyletic groups are typically characterised by shared derived characteristics (synapomorphies), which distinguish organisms in the clade from other organisms. An equivalent term is holophyly.[1]

The word "mono-phyly" means "one-tribe" in Greek.

These definitions have taken some time to be accepted. When the cladistics school of thought became mainstream in the 1960s, several alternative definitions were in use. Indeed, taxonomists sometimes used terms without defining them, leading to confusion in the early literature,[2] a confusion which persists.[3]

The first diagram shows a phylogenetic tree with two monophyletic groups. The several groups and subgroups are particularly situated as branches of the tree to indicate ordered lineal relationships between all the organisms shown. Further, any group may (or may not) be considered a taxon by modern systematics, depending upon the selection of its members in relation to their common ancestor(s); see second and third diagrams.

- ^ Allaby, Michael (2015). A Dictionary of Ecology (5 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191793158.

- ^ Hennig, Willi (1999) [1966]. Phylogenetic Systematics. Translated by Davis, D.; Zangerl, R. (Illinois Reissue ed.). Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. pp. 72–77. ISBN 978-0-252-06814-0.

- ^ Aubert, D. 2015. A formal analysis of phylogenetic terminology: Towards a reconsideration of the current paradigm in systematics. Phytoneuron 2015-66:1–54.