Back ناثان بيدفورد فورست Arabic ناثان بيدفورد فورست ARZ Nathan Bedford Forrest Catalan Nathan Bedford Forrest Czech Nathan Bedford Forrest Danish Nathan Bedford Forrest German Nathan Bedford Forrest Esperanto Nathan Bedford Forrest Spanish Nathan Bedford Forrest Basque نیتن بدفورد فارست Persian

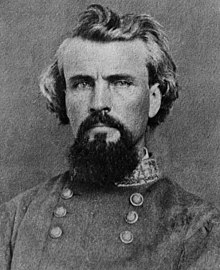

Nathan Bedford Forrest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Nathan Bedford Forrest |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Bed"[1] "Wizard of the Saddle"[2] |

| Born | July 13, 1821 Chapel Hill, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | October 29, 1877 (aged 56) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Buried | Columbia, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Unit |

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Relations |

|

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821 – October 29, 1877) was a 19th-century American slave trader active in the lower Mississippi River valley, a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War, and the first Grand Wizard of the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan, serving from 1867 to 1869.

Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth as a horse and cattle trader, real estate broker, slave jail operator, interstate slave trader, and cotton plantation owner. In June 1861, he enlisted in the Confederate Army and became one of the few soldiers during the war to enlist as a private and be promoted to general without previous military training. An expert cavalry leader, Forrest was given command of a corps and established new doctrines for mobile forces, earning the nickname "The Wizard of the Saddle". He used his cavalry troops as mounted infantry and often deployed artillery as the lead in battle, thus helping to "revolutionize cavalry tactics".[3][4] His role in the massacre of several hundred U.S. Army soldiers at Fort Pillow remains controversial, as the most infamous application of the Confederate no-quarter policy toward black enemy combatants. In April 1864, in what has been called "one of the bleakest, saddest events of American military history",[5] troops under Forrest's command at the Battle of Fort Pillow massacred hundreds of surrendered troops, composed of black soldiers and white Tennessean Southern Unionists fighting for the United States. Forrest was blamed for the slaughter in the U.S. press, and this news may have strengthened the United States's resolve to win the war. Forrest's level of responsibility for the massacre is still debated by historians.[6]

Forrest joined the Ku Klux Klan in 1867 (two years after its founding) and was elected its first Grand Wizard.[7] The group was a secretive network of dens, across the post-war South, where ex-Confederate reactionaries having a good horse and a gun, threatened, assaulted and murdered politically active black people and their allies for political power in a system newly dominated by those whom the unreconstructed termed "niggers, carpetbaggers and scalawags." The Klan, with Forrest at the lead, suppressed the voting rights of blacks through violence and intimidation during the elections of 1868. In 1869, Forrest expressed disillusionment with the terrorist group's lack of discipline,[8] and issued a letter ordering the dissolution of the Ku Klux Klan as well as the destruction of its costumes; he then withdrew from the organization. Forrest later denied being a Klan member,[9] and in the 1870s twice made statements in support of racial harmony and black dignity.[10] During the last years of his life, he served on the board of a railroad and farmed President's Island using convict labor. Forrest died of illness in 1877, at the age of 56.

While scholars generally acknowledge Forrest's skills and acumen as a cavalry leader and tactician, due to his pre-war slave trading and his post-war leadership of the Klan, he is now considered a shameful signifier of a bleaker, less-equal United States. Forrest's racism and use of violence were sanctified by the Lost Cause mythology that was widely promulgated during the nadir of American race relations era, and he continues to be a favorite figure of American white supremacists. As such, in the 21st century, several Forrest monuments and memorials have been removed or renamed to better reflect the current state of race relations in the United States.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 326.

- ^ A.W.R. Hawkins III; Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr.; Spencer C. Tucker (2014). "Forrest, Nathan Bedford (1821–1877)". In Tucker, Spencer C. (ed.). 500 Great Military Leaders [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-758-1. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ Stephen Z. Starr (2007). The Union Cavalry in the Civil War: The War in the West, 1861–1865. LSU Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8071-3293-7. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

...Nathan Bedford Forrest, whom his superiors did not recognize for the military genius he was until it was too late...

- ^ David J Eicher (2002). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 657–. ISBN 978-0-7432-1846-7. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Gwynne, S. C. (2020). Hymns of the Republic: The Story of the Final Year of the American Civil War. Simon and Schuster. p. 332. ISBN 978-1-5011-1623-0. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

Forrest's responsibility for the massacre has been actively debated for a century and a half. Forrest spent much time after the war trying to clear his name. No direct evidence suggests that he ordered the shooting of surrendering or unarmed men, but to fully exonerate him from responsibility is also impossible.

- ^ Tabbert, Mark A. (2006). American Freemasons: Three Centuries of Building Communities. NYU Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780814783023. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ J. Michael Martinez (2012). Terrorist Attacks on American Soil From the Civil War Era to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-4422-0324-2. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

Although Forrest repudiated the group's activities after less than two years, he transformed the budding terrorist organization into an effective mechanism for promoting white supremacy in the Old South.

- ^ Chester L. Quarles (1999). The Ku Klux Klan and Related American Racialist and Antisemitic Organizations: A History and Analysis. McFarland. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7864-0647-0. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

memphis-appealwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).