Back নৱযান Assamese নবযান Bengali/Bangla Navayana Spanish Navayana Finnish नवयान Hindi Navajána Hungarian Navayāna ID នវយាន Cambodian 신승불교 Korean नवयान Marathi

| Navayāna | |

|---|---|

| नवयान | |

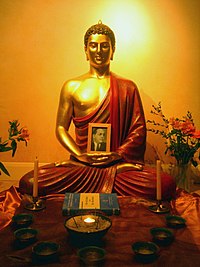

A Navayāna Buddhist shrine with Ambedkar's portrait and The Buddha and His Dhamma book. The photograph is on the event of the 50th Dhammachakra Pravartan Day. | |

| Type | Dharmic |

| Moderator | Bodhisattva Ambedkar |

| Region | India |

| Founder | B. R. Ambedkar |

| Origin | 1956 Deekshabhoomi, Nagpur, India |

| Members | 7.30 million followers (2011) |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Navayāna (Devanagari: नवयान, IAST: Navayāna, meaning "New Vehicle"), otherwise known as Navayāna Buddhism, refers to the socially engaged school of Buddhism founded and developed by the Indian jurist, social reformer, and scholar B. R. Ambedkar;[a] it is otherwise called Neo-Buddhism and Ambedkarite Buddhism It is not any new sect, it is rather application of Buddhist principles for the welfare of many.[1][2]

B. R. Ambedkar was an Indian lawyer, politician, and scholar of Buddhism, and the Drafting Chairman of the Constitution of India. He was born in a Dalit (untouchable) family during the colonial era of India, studied abroad, became a Dalit leader, and announced in 1935 his intent to convert from Hinduism to a different religion,[3] an endeavor which took him to study all the major religions of the world in depth, namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Christianity, and Islam, for nearly 21 years.[4][5][3] The school was otherwise named Ambedkarite Buddhism after him by people after his death.[6] Ambedkar heldHinduism conference on 13 October 1956, announcing his rejection of Hinduism.[7] Thereafter, he left Hinduism and adopted Buddhism as his religious faith, about six weeks before his death.[1][6][7] Its adherents see Navayāna Buddhism not as a sect with radically different ideas, but rather as a new social movement founded on the principles of Buddhism.

In the Buddhist faith, Navayāna is not considered as an independent new branch of Buddhism native to India, distinct from the traditionally recognized branches of Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna[8]—considered to be foundational in the Buddhist tradition.[9][b] It radically re-interprets what Buddhism is;[10][c] Ambedkar regarded Buddhism to be a better alternative than Marxism or Communism, taking into account modern problems within Indian society.[6][11][12]

While the term Navayāna is most commonly used in reference to the movement that Ambedkar founded in India, it is also (more rarely) used in a different sense, to refer to Westernized forms of Buddhism.[13] Ambedkar didn't call his version of Buddhism Navayāna or "Neo-Buddhism".[14] His book, The Buddha and His Dhamma, is considered Bible of Buddhism and seems to be an attempt to unite all Buddhist schools. The followers of Navayāna Buddhism are generally called "Buddhists" (Bauddha) as well as Ambedkarite Buddhists, and rarely Navayāna Buddhists.[15] Almost 90% of Navayāna Buddhists live in Maharashtra.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ a b Tartakov, Gary (2003). Robinson, Rowena (ed.). Religious Conversion in India: Modes, motivations, and meanings. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–213. ISBN 978-0-19-566329-7.

- ^ Queen, Christopher (2015). Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.). A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 524–525. ISBN 978-1-119-14466-3.

- ^ a b Dirks, Nicholas B. (2011). Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the making of modern India. Princeton University Press. pp. 267–274. ISBN 978-1-4008-4094-6.

- ^ "Why Ambedkar chose Buddhism over Hinduism, Islam, Christianity". ThePrint. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Three reasons why Ambedkar embraced Buddhism". The Indian Express. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Zelliot, Eleanor (2015). Jacobsen, Knut A. (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India. Taylor & Francis. pp. 13, 361–370. ISBN 978-1-317-40357-9.

- ^ a b Queen, Christopher (2015). Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.). A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 524–529. ISBN 978-1-119-14466-3.

- ^ Omvedt, Gail (2003). Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and caste (3rd ed.). London, UK; New Delhi, IN; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 2, 3–7, 8, 14–15, 19, 240, 266, 271.

- ^ a b Keown, Damien; Prebish, Charles S. (2013). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-136-98588-1.

- ^ a b Rich, Bruce (2008). To Uphold the World. Penguin Books. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-670-99946-0.[full citation needed]

- ^ Keown, Damien; Prebish, Charles S. (2013). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-1-136-98588-1.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

blackburn1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wiering, Jelle (2 July 2016). ""Others Think I am Airy-fairy": Practicing Navayana Buddhism in a Dutch Secular Climate". Contemporary Buddhism. 17 (2): 369–389. doi:10.1080/14639947.2016.1234751. hdl:11370/5bd3579c-fc6d-45f8-8e69-fa081555ff2a. ISSN 1463-9947. S2CID 151389804.

- ^ Christopher S. Queen (2000). Engaged Buddhism in the West. Wisdom Publications. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-86171-159-8.

- ^ Queen, Christopher (2015). Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.). A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 524–531. ISBN 978-1-119-14466-3.