Back Nouruz Afrikaans نوروز Arabic نوروز ARZ Novruz bayramı Azerbaijani نوروز AZB Науруз Bashkir Наўруз Byelorussian Наўруз BE-X-OLD Норуз Bulgarian নওরোজ Bengali/Bangla

| Nowruz | |

|---|---|

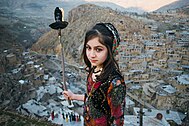

Haft-sin in Iran Azerbaijani man and woman in traditional Nowruz outfits Kurdish girl in Palangan, Iran, during Nowruz festival preparations Kazakh students in traditional Kazakh outfits during a Nowruz musical performance Citizens from the Commonwealth of Independent States dancing in Moscow, Russia, for Nowruz festivities | |

| Observed by | Iranian peoples (originally) Current countries:

|

| Type | Cultural |

| Significance | Vernal equinox; first day of a new year on the Solar Hijri calendar |

| Date | Between 19 and 22 March[25] |

| 2024 date | 03:06:26, 20 March (UTC)[26][27] |

| 2025 date | 09:01:30, 20 March (UTC)[28] |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Nawrouz, Novruz, Nowrouz, Nowrouz, Nawrouz, Nauryz, Nooruz, Nowruz, Navruz, Nevruz, Nowruz, Navruz | |

|---|---|

| Country | Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, India, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan |

| Reference | 02097 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2016 (4th session) |

| List | Representative |

Nowruz (Persian: نوروز [noːˈɾuːz])[t] is the Iranian New Year or Persian New Year.[29][30] Historically, it has been observed by Persians and other Iranian peoples,[31] but is now celebrated by many ethnicities worldwide. It is a festival based on the Northern Hemisphere spring equinox,[32] which marks the first day of a new year on the Solar Hijri calendar; it usually coincides with a date between 19 March and 22 March on the Gregorian calendar.

The roots of Nowruz lie in Zoroastrianism, and it has been celebrated by many peoples across West Asia, Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Black Sea Basin, the Balkans, and South Asia for over 3,000 years.[33][34][35][36] In the modern era, while it is observed as a secular holiday by most celebrants, Nowruz remains a holy day for Zoroastrians,[37] Baháʼís,[38] and Ismaʿili Shia Muslims.[39][40][41]

For the Northern Hemisphere, Nowruz marks the beginning of spring.[27][42] Customs for the festival include various fire and water rituals, celebratory dances, gift exchanges, and poetry recitations, among others; these observances differ between the cultures of the diverse communities that celebrate it.[43]

- ^ "The World Headquarters of the Bektashi Order – Tirana, Albania". komunitetibektashi.org. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "Nevruz in Albania in 2022". officeholidays.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Nowruz". Gulf Hotel Bahrain. 4 March 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ "Nowruz conveys message of secularism, says Gowher Rizvi". United News of Bangladesh. 6 April 2018. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "Xinjiang Uygurs celebrate Nowruz festival to welcome spring". Xinhuanet. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ "Nowruz celebrations in the North Cyprus". Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Nevruz kutlamaları Lefkoşa'da gerçekleştirildi". Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Nowruz Declared as National Holiday in Georgia". civil.ge. 21 March 2010. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Nowruz observed in Indian subcontinent". www.iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ "20 March 2012 United Nations Marking the Day of Nawroz". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Iraq). Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "For Persian Jews, Passover Isn't the Only Major Spring Holiday". Kveller. 19 March 2021. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to the Baha'i New Year, Naw-Ruz!". bahaiteachings.org/. 20 March 2021. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

stanwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Discover Bayan-Olgii". Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ "احتفال النيروز في سلطنة عمان - قناة العالم الاخبارية".

- ^ "Farsnews". Fars News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ "Happy Nauroz: Karachiites ring in the Persian new year in style". The Express Tribune. 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Россия празднует Навруз [Russia celebrates Nowruz]". Golos Rossii (in Russian). 21 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Arabs, Kurds to Celebrate Nowruz as National Day". Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ For Kurds, a day of bonfires, legends, and independence Archived 10 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Dan Murphy. 23 March 2004.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

tajikistanwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ ANADOLU’DA NEVRUZ KUTLAMALARI ve EMİRDAĞ-KARACALAR ÖRNEĞİ Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Anadolu'da Nevruz Kutlamalari

- ^ Emma Sinclair-Webb, Human Rights Watch, "Turkey, Closing ranks against accountability" Archived 12 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Human Rights Watch, 2008. "The traditional Nowrouz/Nowrooz celebrations, mainly celebrated by the Kurdish population in the Kurdistan Region in Iraq, and other parts of Kurdistan in Turkey, Iran, Syria and Armenia and taking place around March 21"

- ^ "General Information of Turkmenistan". sitara.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ "Sweets for a sweeter Iranian new year". Los Angeles Times. 12 March 2021. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ https://7seen.com/index1403.htm [bare URL]

- ^ a b "What is Nowruz? Spring Festival Celebrated by Millions". 19 March 2024. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ https://7seen.com/index1404.htm [bare URL]

- ^ *"They celebrate the new year, which they call Chār shanba sur, on the first Wednesday of April, slightly later than the Iranian new year, Now-Ruz, on 21 March. (...) . The fact that Kurds celebrate the Iranian new year (which they call 'Nawrôz' in Kurdish) does not make them Zoroastrian" – Richard Foltz (2017). "The 'Original' Kurdish Religion? Kurdish Nationalism and the False Conflation of the Yezidi and Zoroastrian Traditions". Journal of Persianate Studies. Volume 10: Issue 1. pp. 93, 95

- "On March 20, 2009, newly-elected us president Barack Obama, speaking on the occasion of the Iranian New Year, struck a conciliatory note by twice (...)" – Navid Pourmokhtari (2014). "Understanding Iran’s Green Movement as a 'movement of movements'". Sociology of Islam. Volume 2: Issue 3–4. p. 153

- "On the occasion of Nowruz 2017 (the Iranian New Year’s Festival celebrated in many countries by various populations) it launched a 'social dialogue initiative' to promote encounters between all components of Iraqi society" – Del Re, E. C. (2019). Minorities and Interreligious Dialogue: From Silent Witnesses to Agents of Change. In Volume 10: Interreligious Dialogue. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill

- ^ * "Nowruz, 'New Day', is a traditional ancient festival which celebrates the starts of the Persian New Year. It is the holiest and most joyful festival of the Zoroastrian year." – Mary Boyce, A. Shapur Shahbazi and Simone Cristoforetti. "NOWRUZ". Encyclopaedia Iranica Online[1] Archived 13 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- "In advance of Nowruz (the Persian New Year holiday), the Varamin Mīrās̱ and Awqāf announced the closure of a total of eight emāmzādehs in Varamin and (...)" – Keelan Overton and Kimia Maleki (2021). "The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20". Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World. Volume 1: Issue 1–2. p. 137

- "The custom of the 'false emir' or 'Nowruz ruler' leading a procession through the city has been traced back to pre-Islamic Nowruz, the traditional Persian New Year." – Michèle Epinette (2014). "MIR-E NOWRUZI" (Archived 13 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine). Encyclopædia Iranica Online.

- "Karimov brought back the very popular Persian New Year, Navro’z (Nowruz) and introduced entirely new commemorative events such as Flag Day, Constitution Day and (...)" – Michal Fux and Amílcar Antonio Barreto. (2020). "Towards a Standard Model of the Cognitive Science of Nationalism – the Calendar". Journal of Cognition and Culture. Volume 20: Issue 5. p. 449

- ^ "What the 3,500-year-old holiday of Nowruz can teach us in 2024". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "International Nowruz Day". United Nations. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "General Assembly Recognizes 21 March as International Day of Nowruz, Also Changes to 23–24 March Dialogue on Financing for Development – Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". UN. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ Kenneth Katzman (2010). Iran: U. S. Concerns and Policy Responses. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4379-1881-6. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ General Assembly Fifty-fifth session 94th plenary meeting Friday, 9 March 2001, 10 a.m. New York. United Nations General Assembly. 9 March 2001. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton (13 September 2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Azoulay, Vincent (1 July 1999). Xenophon and His World: Papers from a Conference Held in Liverpool in July 1999. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-08392-8. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to the Baháʼí New Year, Naw-Ruz!". BahaiTeachings.org. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Isgandarova, Nazila (3 September 2018). Muslim Women, Domestic Violence, and Psychotherapy: Theological and Clinical Issues. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-89155-7. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Navroz". the.Ismaili. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Premji, Zahra (21 March 2021). "Celebrating Navroz, the Persian New Year, through the lens of Ismaili Muslims". CBC.ca. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "What Is Norooz? Greetings, History And Traditions To Celebrate The Persian New Year". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ "Nowruz: Celebrating the New Year on the Silk Roads | Silk Roads Programme". en.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).