Back Kernsplyting Afrikaans Kernspaltung ALS Fisión nucleyar AN انشطار نووي Arabic Fisión nuclear AST Nüvə parçalanması Azerbaijani Ядро бүленеше Bashkir Kondoulu dalėjėmasis BAT-SMG Дзяленне ядра Byelorussian Дзяленьне ядра BE-X-OLD

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

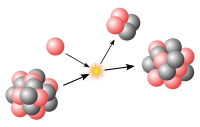

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactive decay.

Nuclear fission was discovered by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann and physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch. Hahn and Strassmann proved that a fission reaction had taken place on 19 December 1938, and Meitner and her nephew Frisch explained it theoretically in January 1939. Frisch named the process "fission" by analogy with biological fission of living cells. In their second publication on nuclear fission in February 1939, Hahn and Strassmann predicted the existence and liberation of additional neutrons during the fission process, opening up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction.

For heavy nuclides, it is an exothermic reaction which can release large amounts of energy both as electromagnetic radiation and as kinetic energy of the fragments (heating the bulk material where fission takes place). Like nuclear fusion, for fission to produce energy, the total binding energy of the resulting elements must be greater than that of the starting element.

Fission is a form of nuclear transmutation because the resulting fragments (or daughter atoms) are not the same element as the original parent atom. The two (or more) nuclei produced are most often of comparable but slightly different sizes, typically with a mass ratio of products of about 3 to 2, for common fissile isotopes.[1][2] Most fissions are binary fissions (producing two charged fragments), but occasionally (2 to 4 times per 1000 events), three positively charged fragments are produced, in a ternary fission. The smallest of these fragments in ternary processes ranges in size from a proton to an argon nucleus.

Apart from fission induced by an exogenous neutron, harnessed and exploited by humans, a natural form of spontaneous radioactive decay (not requiring an exogenous neutron, because the nucleus already has an overabundance of neutrons) is also referred to as fission, and occurs especially in very high-mass-number isotopes. Spontaneous fission was discovered in 1940 by Flyorov, Petrzhak, and Kurchatov[3] in Moscow, in an experiment intended to confirm that, without bombardment by neutrons, the fission rate of uranium was negligible, as predicted by Niels Bohr; it was not negligible.[3]. Despite the possibility of spontaneous fission, it does not play any role for energy production of stars. In contrast to nuclear fusion, which drives the formation of stars and their development, one can consider nuclear fission as neglectable for the evolution of the universe. Accordingly, all elements (with a few exceptions, see "spontaneous fission") which are important for the formation of solar systems, planets and also for all forms of life are not fission products, but rather the results of fusion processes.

The unpredictable composition of the products (which vary in a broad probabilistic and somewhat chaotic manner) distinguishes fission from purely quantum tunneling processes such as proton emission, alpha decay, and cluster decay, which give the same products each time. Nuclear fission produces energy for nuclear power and drives the explosion of nuclear weapons. Both uses are possible because certain substances called nuclear fuels undergo fission when struck by fission neutrons, and in turn emit neutrons when they break apart. This makes a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction possible, releasing energy at a controlled rate in a nuclear reactor or at a very rapid, uncontrolled rate in a nuclear weapon.

The amount of free energy released in the fission of an equivalent amount of 235

U is a million times more than that released in the combustion of methane or from hydrogen fuel cells.[4]

The products of nuclear fission, however, are on average far more radioactive than the heavy elements which are normally fissioned as fuel, and remain so for significant amounts of time, giving rise to a nuclear waste problem. However, the seven long-lived fission products make up only a small fraction of fission products. Neutron absorption which does not lead to fission produces plutonium (from 238

U) and minor actinides (from both 235

U and 238

U) whose radiotoxicity is far higher than that of the long lived fission products. Concerns over nuclear waste accumulation and the destructive potential of nuclear weapons are a counterbalance to the peaceful desire to use fission as an energy source. The thorium fuel cycle produces virtually no plutonium and much less minor actinides, but 232

U - or rather its decay products - are a major gamma ray emitter. All actinides are fertile or fissile and fast breeder reactors can fission them all albeit only in certain configurations. Nuclear reprocessing aims to recover usable material from spent nuclear fuel to both enable uranium (and thorium) supplies to last longer and to reduce the amount of "waste". The industry term for a process that fissions all or nearly all actinides is a "closed fuel cycle".

- ^ M. G. Arora & M. Singh (1994). Nuclear Chemistry. Anmol Publications. p. 202. ISBN 81-261-1763-X.

- ^ Gopal B. Saha (1 November 2010). Fundamentals of Nuclear Pharmacy. Springer. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-1-4419-5860-0.

- ^ a b Петржак, Константин (1989). "Как было открыто спонтанное деление" [How spontaneous fission was discovered]. In Черникова, Вера (ed.). Краткий Миг Торжества — О том, как делаются научные открытия [Brief Moment of Triumph — About making scientific discoveries] (in Russian). Наука. pp. 108–112. ISBN 5-02-007779-8.

- ^ Younes, Walid; Loveland, Walter (2021). An Introduction to Nuclear Fission. Springer. pp. 28–30. ISBN 9783030845940.