| Ordinance of Secession | |

|---|---|

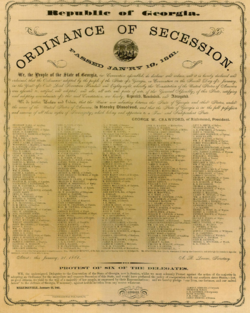

Facsimile of the 1861 Ordinance of Secession signed by 293 delegates to the Georgia Secession Convention at the statehouse in Milledgeville, Georgia, January 21, 1861 | |

| Created | c. January 20, 1861 |

| Ratified | Ratified January 19, 1861 vote was 208 yeas 89 nays Signed January 21, 1861 by 293 delegates Enacted January 22, 1861 |

| Location | Engrossed copy: University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Library |

| Author(s) | George W. Crawford et al. Engrosser: H. J. G. Williams |

| Signatories | 293 delegates to The Georgia Secession Convention of 1861 |

| Purpose | To announce Georgia's formal intent to secede from the Union. |

An Ordinance of Secession was the name given to multiple resolutions[1] drafted and ratified in 1860 and 1861, at or near the beginning of the Civil War, by which each seceding slave-holding Southern state or territory formally declared secession from the United States of America. South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas also issued separate documents purporting to justify secession.

Adherents of the Union side in the Civil War regarded secession as illegal by any means and President Abraham Lincoln, drawing in part on the legacy of President Andrew Jackson, regarded it as his job to preserve the Union by force if necessary. However, President James Buchanan, in his State of the Union Address of December 3, 1860, stated that the Union rested only upon public opinion and that conciliation was its only legitimate means of preservation; President Thomas Jefferson also had suggested in 1816, after his presidency but in official correspondence, that secession of some states might be desirable.

Beginning with South Carolina in December 1860, eleven Southern states and one territory[2] both ratified an ordinance of secession and effected de facto secession by some regular or purportedly lawful means, including by state legislative action, special convention, or popular referendum, as sustained by state public opinion and mobilized military force. Both sides in the Civil War regarded these eleven states and territory as de facto seceding.

Two other Southern states, Missouri and Kentucky, attempted secession ineffectively or only by irregular means. These two states remained within the Union, but were regarded by the Confederacy as having seceded. Two remaining Southern states, Delaware and Maryland, rejected secession and were not regarded by either side as having seceded. No other state considered secession. In 1863 a Unionist government in western Virginia created a new state from 50 western counties which entered the Union as West Virginia. The new state contained 24 counties that had ratified Virginia's secession ordinance.[3]

- ^ Mintz, S.; McNeil, S. "Secession Ordinances of 13 Confederate States". Digital History. University of Houston. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "Confederate Arizona had a population of less than 13,000 as tabulated by Census of 1860". Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Curry, Richard Orr, A House Divided, A Study of Statehood Politics and the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1964, pg. 49