Back Ottomaanse Kalifaat Afrikaans الخلافة العثمانية Arabic উসমানীয় খিলাফত Bengali/Bangla Osmanisches Kalifat German Οθωμανικό Χαλιφάτο Greek Otomandar Kalifa-herria Basque خلافت عثمانی Persian ऑटोमन ख़िलाफ़त Hindi Kekhalifahan Utsmaniyah ID Califfato ottomano Italian

Office of the caliphate خلافت مقامى Hilâfet makamı | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1517–1924 | |||||||

| Capital | Constantinople | ||||||

| Working languages | Ottoman Turkish (dynastic) Arabic (religious) | ||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||

| Government | Hereditary caliphate under an empire (1517–1922) Elective caliphate under a parliament (1922–1924) | ||||||

| Caliph | |||||||

• 1517–1520 | Selim I (first) | ||||||

• 1922–1924 | Abdülmecid II (last) | ||||||

| Established | |||||||

• Al-Mutawakkil III allegedly surrenders his title over to Selim I | 1517 | ||||||

| 1924 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

|

The Ottoman Caliphate (Ottoman Turkish: خلافت مقامى, romanized: hilâfet makamı, lit. 'office of the caliphate') was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty, rulers of the Ottoman Empire, to be the caliphs of Islam in the late medieval and early modern era.

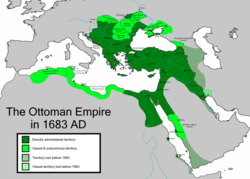

Ottoman rulers first assumed the style of caliph in the 14th century, though did at that point not claim religious authority beyond their own borders. After the conquest of Mamluk Egypt by Sultan Selim I in 1517 and the abolition of the Mamluk-controlled Abbasid Caliphate, Selim and his successors ruled one of the strongest states in the world and gained control of Mecca and Medina, the religious and cultural centers of Islam. The claim to be caliphs transitioned into a claim to universal caliphal authority, similar to that held by the Abbasid Caliphate prior to the sack of Baghdad in 1258. Further Ottoman victories, the dynasty's geopolitical dominance in the 16th–17th centuries, and the lack of rival claimants strengthened the Ottoman claim to be the leaders of the Muslim world.

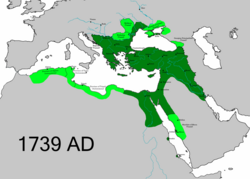

Following territorial losses in the 18th and 19th centuries, the use of caliphal authority by the Ottomans reached its height under Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876–1909), who attempted to cultivate support for the Ottoman Empire through a Pan-Islamist foreign policy. Abdul-Hamid's absolutist rule came to an end through the Young Turk Revolution of 1908. The caliphal office was weakened in domestic politics, though was retained due to its usefulness in international diplomacy. At the beginning of World War I, Sultan Mehmed V proclaimed a jihad against the Entente, though this was largely ineffectual. The legitimacy and authority of the Ottoman Caliphate was damaged by the Great Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the end of the war, which saw the empire lose all of its Arab territories.

The Ottoman Empire came to an end following the partition of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922), which established the modern Republic of Turkey. The last Ottoman caliph, Abdülmecid II, retained his position under the republic until the abolition of the caliphate on 3 March 1924, as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's secular reforms. The imperial Osmanoğlu family was also exiled from Turkey.

With the establishments of Sufi orders like the Bayramiyya and Mawlawiyya under the Ottoman Caliphate, the mystical side of Islam, Sufism, flourished.[1][2][3][4]

- ^ Algar, Ayla Esen (January 1992). The Dervish Lodge: Architecture, Art, and Sufism in Ottoman Turkey. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520070608.

- ^ Sirriyeh, Elizabeth (2005). Sufi Visionary of Ottoman Damascus: ʻAbd Al-Ghanī Al-Nābulusī, 1641-1731. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415341653.

- ^ Wasserstein, David J.; Ayalon, Ami (17 June 2013). Mamluks and Ottomans: Studies in Honour of Michael Winter. Routledge. ISBN 9781136579172.

- ^ ́Goston, Ga ́bor A.; Masters, Bruce Alan (21 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase. ISBN 9781438110257.