Back Османтәи аимпериа Abkhazian Turuki Utsmani ACE Осмэн Пачъыхьыгъо ADY Ottomaanse Ryk Afrikaans Osmanisches Reich ALS የኦቶማን መንግሥት Amharic Imperio Otomán AN Oþomanisce Rīce ANG Ijọn̄-ubọọn̄ Otoman ANN الدولة العثمانية Arabic

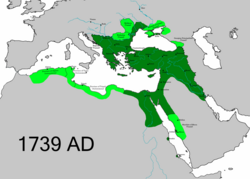

The Ottoman Empire[k] (/ˈɒtəmən/ ⓘ), also called the Turkish Empire,[23][24] was an imperial realm[l] that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Central Europe, between the early 16th and early 18th centuries.[25][26][27]

The empire emerged from a beylik, or principality, founded in northwestern Anatolia in c. 1299 by the Turkoman tribal leader Osman I. His successors conquered much of Anatolia and expanded into the Balkans by the mid-14th century, transforming their petty kingdom into a transcontinental empire. The Ottomans ended the Byzantine Empire with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II, which marked the Ottomans' emergence as a major regional power in the Balkans and in Anatolia in the second half of the 15th century. Under Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), the empire reached the zenith of its power, prosperity, and political development expanding its influence further into Middle East and Central Europe. With its capital at Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) and control over a significant portion of the Mediterranean Basin, the Ottoman Empire was at the centre of interactions between the Middle East and Europe for six centuries. Ruling over so many peoples, the empire granted varying levels of autonomy to its many confessional communities, or millets, to manage their own affairs per Islamic law.

While the Ottoman Empire was once thought to have entered a period of decline after the death of Suleiman the Magnificent, modern academic consensus posits that the empire continued to maintain a flexible and strong economy, society and military into much of the 18th century. However, during a long period of peace from 1740 to 1768, Ottoman military and bureaucratic systems fell behind those of its chief European rivals, the Habsburg and Russian empires. The Ottomans consequently suffered severe military defeats in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, culminating in the loss of both territory and global prestige.

In 1826, Sultan Mahmud II abolished the Janissary corps following the Auspicious Incident, which had been roadblocking attempts at reform. This prompted a comprehensive process of reform and modernization known as the Tanzimat; over the course of the 19th century, the Ottoman state became vastly more powerful and organized internally, despite suffering further territorial losses, especially in the Balkans, where a number of new states emerged. These new states emerged as a consequence to the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire. A state ideology of Ottomanism, or the unity of the many ethno-religious groups in the Empire under the sovereignty of the House of Osman, attempted to counter this trend. The Ottoman Empire joined the Concert of Europe with the 1856 Treaty of Paris. In the 1876 revolution, the Ottoman Empire attempted constitutional monarchy, before reverting to a royalist dictatorship under Abdul Hamid II, following the Great Eastern Crisis.

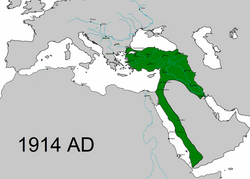

Over the course of the late 19th century, Ottoman intellectuals known as Young Turks sought to liberalize and rationalize society and politics along Western lines, culminating in the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which reestablished a constitutional monarchy. However, following the disastrous Balkan Wars, the CUP became increasingly radicalized and nationalistic, leading a coup d'état in 1913 that established a one-party regime. The CUP allied with the German Empire hoping to escape from the diplomatic isolation that had contributed to its recent territorial losses; it thus joined World War I on the side of the Central Powers. While the empire was able to largely hold its own during the conflict, it struggled with internal dissent, especially the Arab Revolt. During this period, the Ottoman government engaged in genocide against Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks.

In the aftermath of World War I, the victorious Allied Powers occupied and partitioned the Ottoman Empire, which lost its southern territories to the United Kingdom and France. The successful Turkish War of Independence, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk against the occupying Allies, led to the emergence of the Republic of Turkey in the Anatolian heartland and the abolition of the Ottoman monarchy in 1922, formally ending the Ottoman Empire.

- ^ McDonald, Sean; Moore, Simon (20 October 2015). "Communicating Identity in the Ottoman Empire and Some Implications for Contemporary States". Atlantic Journal of Communication. 23 (5): 269–283. doi:10.1080/15456870.2015.1090439. ISSN 1545-6870. S2CID 146299650. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford; Shaw, Ezel (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-29166-8.

- ^ Atasoy & Raby 1989, p. 19–20.

- ^ M. Tayyib Gökbilgin (1988–2016). "Edirne". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam (44+2 vols.) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies.

- ^ Edhem, Eldem (21 May 2010). "Istanbul". In Gábor, Ágoston; Masters, Bruce Alan (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, all previous names were abandoned and Istanbul came to designate the entire city.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977b). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 2: Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808–1975. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511614972. ISBN 9780511614972.

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977b, p. 386, volume 2; Robinson (1965). The First Turkish Republic. p. 298.; Society (4 March 2014). "Istanbul, not Constantinople". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2019.)

- ^ Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian Learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. pp. 88–89.

As the Ottoman Turks learned Persian, the language and the culture it carried seeped not only into their court and imperial institutions but also into their vernacular language and culture. The appropriation of Persian, both as a second language and as a language to be steeped together with Turkish, was encouraged notably by the sultans, the ruling class, and leading members of the mystical communities.

- ^ Tezcan, Baki (2012). "Ottoman Historical Writing". In Rabasa, José (ed.). The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400–1800 The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400–1800. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–211.

Persian served as a 'minority' prestige language of culture at the largely Turcophone Ottoman court.

- ^ Flynn, Thomas O. (2017). The Western Christian Presence in the Russias and Qājār Persia, c. 1760–c. 1870. Brill. p. 30. ISBN 978-90-04-31354-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Fortna, B. (2012). Learning to Read in the Late Ottoman Empire and the Early Turkish Republic. Springer. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-230-30041-5. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Although in the late Ottoman period Persian was taught in the state schools...

- ^ Spuler, Bertold (2003). Persian Historiography and Geography. Pustaka Nasional Pte. p. 68. ISBN 978-9971-77-488-2. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

On the whole, the circumstance in Turkey took a similar course: in Anatolia, the Persian language had played a significant role as the carrier of civilization. [...] where it was at time, to some extent, the language of diplomacy [...] However Persian maintained its position also during the early Ottoman period in the composition of histories and even Sultan Salim I, a bitter enemy of Iran and the Shi'ites, wrote poetry in Persian. Besides some poetical adaptations, the most important historiographical works are: Idris Bidlisi's flowery "Hasht Bihist", or Seven Paradises, begun in 1502 by the request of Sultan Bayazid II and covering the first eight Ottoman rulers...

- ^ Fetvacı, Emine (2013). Picturing History at the Ottoman Court. Indiana University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-253-00678-3. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Persian literature, and belles-lettres in particular, were part of the curriculum: a Persian dictionary, a manual on prose composition; and Sa'dis 'Gulistan', one of the classics of Persian poetry, were borrowed. All these titles would be appropriate in the religious and cultural education of the newly converted young men.

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan; Melville, Charles, eds. (359). Persian Historiography: A History of Persian Literature. Vol. 10. Bloomsbury. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-85773-657-4. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Persian held a privileged place in Ottoman letters. Persian historical literature was first patronized during the reign of Mehmed II and continued unabated until the end of the 16th century.

- ^ Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. p. 92 (note 27).

Though Persian, unlike Arabic, was not included in the typical curriculum of an Ottoman madrasa, the language was offered as an elective course or recommended for study in some madrasas. For those Ottoman madrasa curricula featuring Persian, see Cevat İzgi, Osmanlı Medreselerinde İlim, 2 vols. (Istanbul: İz, 1997),1: 167–169.

- ^ Ayşe Gül Sertkaya (2002). "Şeyhzade Abdurrezak Bahşı". In György Hazai (ed.). Archivum Ottomanicum. Vol. 20. pp. 114–115. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

As a result, we can claim that Şeyhzade Abdürrezak Bahşı was a scribe lived in the palaces of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror and his son Bayezid-i Veli in the 15th century, wrote letters (bitig) and firmans (yarlığ) sent to Eastern Turks by Mehmed II and Bayezid II in both Uighur and Arabic scripts and in East Turkestan (Chagatai) language.

- ^ a b Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Würzburg: Orient-Institut Istanbul. pp. 21–51. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019. (info page on book Archived 20 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine at Martin Luther University) // CITED: p. 26 (PDF p. 28): "French had become a sort of semi-official language in the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the Tanzimat reforms.[...] It is true that French was not an ethnic language of the Ottoman Empire. But it was the only Western language which would become increasingly widespread among educated persons in all linguistic communities."

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lambton-1995was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pamuk, Şevket (2000). A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-521-44197-8. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

The Ottomans began to strike coins in the name of Orhan Bey in 1326. These earliest coins carried inscriptions such as "the great Sultan, Orhan son of Osman" [...] Ottoman historiography has adopted 1299 as the date for the foundation of the state. 1299 might represent the date at which the Ottomans finally obtained their independence from the Seljuk sultan at Konya. Probably, they were forced at the same time, or very soon thereafter, to accept the overlordship of the Ilkhanids [...] Numismatic evidence thus suggest that independence did not really occur until 1326.

- ^ a b c Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 498. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. ISSN 0020-8833. JSTOR 2600793. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 223. ISSN 1076-156X. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-275-97888-4.

- ^ P., E. A. (1916). "Review of The Caliph's Last Heritage: A Short History of the Turkish Empire". The Geographical Journal. 47 (6): 470–472. doi:10.2307/1779249. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1779249. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Baykara, Prof. Tuncer (2017). "A Study into the Concepts of Turkey and Turkistan which were used for the Ottoman State in XIXth Century". Journal of Atatürk and the History of Turkish Republic. 1: 179–190. Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (12 August 2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. Purdue University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wq7kw.12. ISBN 978-1-61249-179-0. JSTOR j.ctt6wq7kw. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Szabó, János B. (2019). "The Ottoman Conquest in Hungary: Decisive Events (Belgrade 1521, Mohács 1526, Vienna 1529, Buda 1541) and Results". The Battle for Central Europe. Brill. pp. 263–275. doi:10.1163/9789004396234_013. ISBN 978-90-04-39623-4. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Moačanin, Nenad (2019). "The Ottoman Conquest and Establishment in Croatia and Slavonia". The Battle for Central Europe. Brill. pp. 277–286. doi:10.1163/9789004396234_014. ISBN 978-90-04-39623-4. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).