Back Neerslag Afrikaans هطول Arabic Precipitación (meteoroloxía) AST Atmosfer yağıntıları Azerbaijani Krėtolē BAT-SMG Presipitasyon BCL Атмасферныя ападкі Byelorussian Атмасфэрныя ападкі BE-X-OLD Валеж Bulgarian လော့လင်ꩻ BLK

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls from clouds due to gravitational pull.[1] The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, sleet, snow, ice pellets, graupel and hail. Precipitation occurs when a portion of the atmosphere becomes saturated with water vapor (reaching 100% relative humidity), so that the water condenses and "precipitates" or falls. Thus, fog and mist are not precipitation; their water vapor does not condense sufficiently to precipitate, so fog and mist do not fall. (Such a non-precipitating combination is a colloid.) Two processes, possibly acting together, can lead to air becoming saturated with water vapor: cooling the air or adding water vapor to the air. Precipitation forms as smaller droplets coalesce via collision with other rain drops or ice crystals within a cloud. Short, intense periods of rain in scattered locations are called showers.[2]

Moisture that is lifted or otherwise forced to rise over a layer of sub-freezing air at the surface may be condensed by the low temperature into clouds and rain. This process is typically active when freezing rain occurs. A stationary front is often present near the area of freezing rain and serves as the focus for forcing moist air to rise. Provided there is necessary and sufficient atmospheric moisture content, the moisture within the rising air will condense into clouds, namely nimbostratus and cumulonimbus if significant precipitation is involved. Eventually, the cloud droplets will grow large enough to form raindrops and descend toward the Earth where they will freeze on contact with exposed objects. Where relatively warm water bodies are present, for example due to water evaporation from lakes, lake-effect snowfall becomes a concern downwind of the warm lakes within the cold cyclonic flow around the backside of extratropical cyclones. Lake-effect snowfall can be locally heavy. Thundersnow is possible within a cyclone's comma head and within lake effect precipitation bands. In mountainous areas, heavy precipitation is possible where upslope flow is maximized within windward sides of the terrain at elevation. On the leeward side of mountains, desert climates can exist due to the dry air caused by compressional heating. Most precipitation occurs within the tropics and is caused by convection.[3]

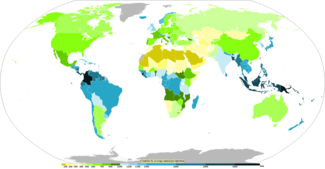

Precipitation is a major component of the water cycle, and is responsible for depositing most of the fresh water on the planet. Approximately 505,000 cubic kilometres (121,000 cu mi) of water falls as precipitation each year: 398,000 cubic kilometres (95,000 cu mi) over oceans and 107,000 cubic kilometres (26,000 cu mi) over land.[4] Given the Earth's surface area, that means the globally averaged annual precipitation is 990 millimetres (39 in), but over land it is only 715 millimetres (28.1 in). Climate classification systems such as the Köppen climate classification system use average annual rainfall to help differentiate between differing climate regimes. Global warming is already causing changes to weather, increasing precipitation in some geographies, and reducing it in others, resulting in additional extreme weather.[5]

Precipitation may occur on other celestial bodies. Saturn's largest satellite, Titan, hosts methane precipitation as a slow-falling drizzle,[6] which has been observed as rain puddles at its equator[7] and polar regions.[8][9]

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

- ^ "Precipitation". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. 2009. Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Scott Sistek (December 26, 2015). "What's the difference between 'rain' and 'showers'?". KOMO-TV. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ Adler, Robert F.; et al. (December 2003). "The Version-2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Precipitation Analysis (1979–Present)". Journal of Hydrometeorology. 4 (6): 1147–1167. Bibcode:2003JHyMe...4.1147A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1018.6263. doi:10.1175/1525-7541(2003)004<1147:TVGPCP>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 16201075.

- ^ Chowdhury's Guide to Planet Earth (2005). "The Water Cycle". WestEd. Archived from the original on 2011-12-26. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ Seneviratne, Sonia I.; Zhang, Xuebin; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; et al. (2021). "Chapter 11: Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate" (PDF). IPCC AR6 WG1 2021.

- ^ Graves, S. D. B.; McKay, C. P.; Griffith, C. A.; Ferri, F.; Fulchignoni, M. (2008-03-01). "Rain and hail can reach the surface of Titan". Planetary and Space Science. 56 (3): 346–357. Bibcode:2008P&SS...56..346G. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2007.11.001. ISSN 0032-0633.

- ^ "Cassini Sees Seasonal Rains Transform Titan's Surface". NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- ^ "Changes in Titan's Lakes". NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- ^ "Cassini Saw Rain Falling at Titan's North Pole". Universe Today. 2019-01-18. Retrieved 2020-12-15.