Back رئاسة جورج واشنطن Arabic Kabinett Washington German George Washingtonin hallitus Finnish Présidence de George Washington French הקבינט של ארצות הברית בממשל ג'ורג' וושינגטון HE Presidenza di George Washington Italian Kabinet-Washington Dutch ਜੌਰਜ ਵਾਸ਼ਿੰਗਟਨ ਦੀ ਪ੍ਰੈਜੀਡੈਂਸੀ Punjabi Gabinet George’a Washingtona Polish Presidência de George Washington Portuguese

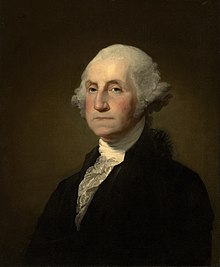

Washington depicted in a 1796 portrait by Gilbert Stuart | |

| Presidency of George Washington April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Independent |

| Election | |

| Seat | |

|

| |

| Library website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

1st President of the United States

First term

Second term

Legacy

|

||

The presidency of George Washington began on April 30, 1789, when George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1797. Washington took office after the 1788–1789 presidential election, the nation's first quadrennial presidential election, in which he was elected unanimously by the Electoral College. Washington was re-elected unanimously in the 1792 presidential election and chose to retire after two terms. He was succeeded by his vice president, John Adams of the Federalist Party.

Washington, who had established his preeminence among the new nation's Founding Fathers through his service as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and as president of the 1787 constitutional convention, was widely expected to become the first president of the United States under the new Constitution, though he desired to retire from public life. In his first inaugural address, Washington expressed both his reluctance to accept the presidency and his inexperience with the duties of civil administration, though he proved an able leader.

He presided over the establishment of the new federal government, appointing all of the high-ranking officials in the executive and judicial branches, shaping numerous political practices, and establishing the site of the permanent capital of the United States. He supported Alexander Hamilton's economic policies whereby the federal government assumed the debts of the state governments and established the First Bank of the United States, the United States Mint, and the United States Customs Service. Congress passed the Tariff of 1789, the Tariff of 1790, and an excise tax on whiskey to fund the government and, in the case of the tariffs, address the trade imbalance with Britain. Washington personally led federalized soldiers in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion, which arose in opposition to the administration's taxation policies. He directed the Northwest Indian War, which saw the United States establish control over Native American tribes in the Northwest Territory. In foreign affairs, he assured domestic tranquility and maintained peace with the European powers despite the raging French Revolutionary Wars by issuing the 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality. He also secured two important bilateral treaties, the 1794 Jay Treaty with Great Britain and the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain, both of which fostered trade and helped secure control of the American frontier. To protect American shipping from Barbary pirates and other threats, he re-established the United States Navy with the Naval Act of 1794.

Greatly concerned about the growing partisanship within the government and the detrimental impact political parties could have on the fragile unity of the nation, Washington struggled throughout his eight-year presidency to hold rival factions together. He was, and remains, the only U.S. president never to be formally affiliated with a political party.[1] Despite his efforts, debates over Hamilton's economic policy, the French Revolution, and the Jay Treaty deepened ideological divisions. Those who supported Hamilton formed the Federalist Party, while his opponents coalesced around Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and formed the Democratic-Republican Party. While criticized for furthering the partisanship he sought to avoid by identifying himself with Hamilton, Washington is nonetheless considered by scholars and political historians as one of the greatest presidents in American history, usually ranking in the top three with Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

- ^ "George Washington's Farewell Warning". POLITICO Magazine. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2018.