Back Hervormingsoorlog Afrikaans حرب الإصلاح Arabic Guerra de Reforma Catalan Reforma Milito Esperanto Guerra de Reforma Spanish Guerre de réforme French レフォルマ戦争 Japanese რეფორმის ომი Georgian Tlapapatiliztli yāōyōtl NAH Hervormingsoorlog Dutch

| Reform War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

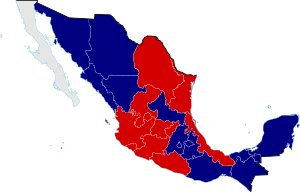

Mexico in 1858

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Benito Juárez Santos Degollado Ignacio Zaragoza Santiago Vidaurri Jesús González Ortega Emilio Langberg |

Félix Zuloaga Miguel Miramón Leonardo Márquez Tomás Mejía Luis G. Osollo | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,000 Americans |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

103 Americans killed by Mexican liberals 4 American soldiers kidnapped in a cross-border raid by Mexican liberals and later executed |

| ||||||

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Reform War, or War of Reform (Spanish: Guerra de Reforma), also known as the Three Years' War (Spanish: Guerra de los Tres Años), and the Mexican Civil War,[2] was a complex civil conflict in Mexico fought between Mexican liberals and conservatives with regional variations over the promulgation of Constitution of 1857. It has been called the "worst civil war to hit Mexico between the War of Independence of 1810–21 and the Revolution of 1910–20".[3] Following the liberals' overthrow of the dictatorship of conservative Antonio López de Santa Anna, liberals passed a series of laws codifying their political program. These laws were incorporated into the new constitution. It aimed to limit the political power of the executive branch, as well as the political, economic, and cultural power of the Catholic Church. Specific measures were the expropriation of Church property; separation of church and state; reduction of the power of the Mexican Army by elimination of their special privileges; strengthening the secular state through public education; and measures to develop the nation economically.[4]

The constitution had been promulgated on 5 February 1857 was to come into force on 16 September 1857. Predictably there was fierce opposition from Conservatives and the Catholic Church over its anti-clerical provisions, but there were also moderate liberals, including President Ignacio Comonfort, who considered the constitution too radical and likely to trigger a civil war. The Lerdo Law forced the sale of most of the Church's rural properties. The measure was not exclusively aimed at the Catholic Church, but also Mexico's indigenous peoples, which were forced to sell sizeable portions of their communal lands. Controversy was further inflamed when the Catholic Church decreed the excommunication of civil servants who took a government-mandated oath upholding the new constitution, which left Catholic civil servants with the choice of losing their jobs or being excommunicated.[5]

General Félix Zuloaga led army troops to the capital and closed congress and issued the Plan of Tacubaya on 17 December 1857. The constitution was nullified, President Comonfort was initially signed onto the plan and was retained in the presidency and given emergency powers. Some liberal politicians were arrested, including the president of the Supreme Court of Justice, Benito Juárez.[6] Comonfort, hoping to establish a more moderate government, found himself triggering a civil war and began to back away from Zuloaga. On 11 January 1858, Comonfort resigned and went into exile. He was constitutionally succeeded by Juárez as president of the Supreme Court. The nation's states subsequently chose to side with either the Mexico City-based government of Zuloaga or that of Juárez, which established itself at the strategic port of Veracruz. Initial choices for one side or the other often shifted over time. The first year of the war was marked by repeated conservative victories, but the liberals remained entrenched in the nation's coastal regions, including their capital at the port of Veracruz, which gave them access to vital customs revenue that could fund their forces.

Both governments attained international recognition, the liberals by the United States and the conservatives by France, the United Kingdom, and Spain. The liberals negotiated the McLane–Ocampo Treaty with the United States in 1859. If ratified the treaty would have given the liberal regime cash, but it would have also granted the United States perpetual military and economic rights on Mexican territory. The treaty failed to pass in the U.S. Senate, but the U.S. Navy still helped protect Juárez's government in Veracruz.

Liberals accumulated victories on the battlefield until conservative forces surrendered on 22 December 1860. Juárez returned to Mexico City on 11 January 1861 and held presidential elections in March.[7] Although the conservative forces lost the war, guerrillas remained active in the countryside and later joined the upcoming French intervention to help establish the Second Mexican Empire.[8]

- ^ "Juárez es apoyado por tropas de EU en Guerra de Reforma" [Juarez is aided by U.S. troops in the War of Reform] (in Spanish). Mexico: El Dictamen. 2012-10-08. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

- ^ Will Fowler, The Grammar of Civil War: A Mexican Case Study, 1857-61. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2022

- ^ Fowler, The Grammar of Civil War, p. 43

- ^ Sinkin, The Mexican Reform, 169.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fowler, The Grammar of Civil War p.43

- ^ Hamnett, Brian. Juárez. New York: Longman 1994, 255

- ^ Sinkin, The Mexican Reform, 177.