Back رينهولد نيبوهر Arabic رينهولد نيبوهر ARZ Райнхолд Нибур Bulgarian Reinhold Niebuhr Catalan Reinhold Niebuhr Czech Reinhold Niebuhr German Reinhold Niebuhr Esperanto Reinhold Niebuhr Spanish راینهولد نیبور Persian Reinhold Niebuhr Finnish

| Part of a series on |

| Dialectical theology |

|---|

|

|

|

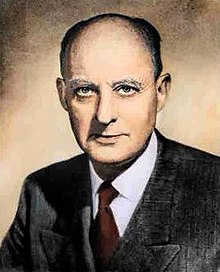

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr[a] (June 21, 1892 – June 1, 1971) was an American Reformed theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr was one of America's leading public intellectuals for several decades of the 20th century and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. A public theologian, he wrote and spoke frequently about the intersection of religion, politics, and public policy, with his most influential books including Moral Man and Immoral Society and The Nature and Destiny of Man.

Starting as a minister with working-class sympathies in the 1920s and sharing with many other ministers a commitment to pacifism and socialism, his thinking evolved during the 1930s to neo-orthodox realist theology as he developed the philosophical perspective known as Christian realism.[27][verification needed][28] He attacked utopianism as ineffectual for dealing with reality. Niebuhr's realism deepened after 1945 and led him to support American efforts to confront Soviet communism around the world. A powerful speaker, he was one of the most influential thinkers of the 1940s and 1950s in public affairs.[29] Niebuhr battled with religious liberals over what he called their naïve views of the contradictions of human nature and the optimism of the Social Gospel, and battled with religious conservatives over what he viewed as their naïve view of scripture and their narrow definition of "true religion". During this time he was viewed by many as the intellectual rival of John Dewey.[30]

Niebuhr's contributions to political philosophy include using the resources of theology to argue for political realism. His work has also significantly influenced international relations theory, leading many scholars to move away from idealism and embrace realism.[b] A large number of scholars, including political scientists, political historians, and theologians, have noted his influence on their thinking. Aside from academics, activists such as Myles Horton and Martin Luther King Jr., and numerous politicians have also cited his influence on their thought,[31][32][33][34] including Hillary Clinton, Hubert Humphrey, and Dean Acheson, as well as presidents Barack Obama[35][36] and Jimmy Carter.[37] Niebuhr has also influenced the Christian right in the United States. The Institute on Religion and Democracy, a conservative think tank founded in 1981, has adopted Niebuhr's concept of Christian realism on their social and political approaches.[38]

Aside from his political commentary, Niebuhr is also known for having composed the Serenity Prayer, a widely recited prayer which was popularized by Alcoholics Anonymous.[39][40] Niebuhr was also one of the founders of both Americans for Democratic Action and the International Rescue Committee and also spent time at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, while serving as a visiting professor at both Harvard and Princeton.[41][42][43] He was also the brother of another prominent theologian, H. Richard Niebuhr.

- ^ Leatt 1973, p. 40.

- ^ Hartt, Julian N. (March 23, 1986). "Reinhold Neibuhr: Conscience of the Liberals". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Maeshiro, Kelly (2017). "The Political Theology of Reinhold Niebuhr". Academia.edu: 17. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Hartman 2015, p. 297.

- ^ Granfield, Patrick (December 16, 1966). "An Interview with Reinhold Niebuhr". Commonweal. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Olson 2013, p. 360.

- ^ Rice 2013, p. 80.

- ^ Dorrien 2011, p. 257.

- ^ Tarbox 2007, p. 14.

- ^ Jensen 2014.

- ^ Mitchell 2011.

- ^ Tůmová 2015.

- ^ Kermode, Frank (April 25, 1999). "The Power to Enchant". The New Republic. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ^ Davis, David Brion (February 13, 1986). "American Jeremiah". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ Byers 1998, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Steinfels, Peter (May 25, 2007). "Two Social Ethicists and the National Landscape". The New York Times. p. B6. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ^ Gordon, David (2018). "Review of Jean Bethke Elshtain: Politics, Ethics, and Society, by Michael Le Chevallier". Library Journal. Vol. 143, no. 8. Media Source. p. 69. ISSN 0363-0277. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Larkman, Connie (February 6, 2018). "UCC Mourns the Loss of Theologian, Teacher, Author, Activist Gabe Fackre". Cleveland, Ohio: United Church of Christ. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Fleming 2015, pp. 64, 78; Wright 1991, p. 71.

- ^ Loder-Jackson 2013, p. 78.

- ^ Reinitz 1980, p. 203.

- ^ Freund 2007.

- ^ Morgan 2010, p. 263.

- ^ Stone 2014, p. 279.

- ^ Reinhold Niebuhr in the Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia

- ^ Reinhold Niebuhr in the American Heritage Dictionary

- ^ R. M. Brown 1986, pp. xv–xiv.

- ^ McWilliams, Wilson Carey (1962). "Reinhold Niebuhr: New Orthodoxy for Old Liberalism". American Political Science Review. 56 (4): 874–885. doi:10.2307/1952790. ISSN 1537-5943. JSTOR 1952790.

- ^ Schlesinger, Arthur Jr. (September 18, 2005). "Forgetting Reinhold Niebuhr". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ Rice 1993.

- ^ Urquhart, Brian (March 26, 2009). "What You Can Learn from Reinhold Niebuhr". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Reinhold Niebuhr and the Political Moment". Religion & Ethics Newseekly. PBS. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013.

- ^ Hoffman, Claire. "Under God: Spitzer, Niebuhr and the Sin of Pride". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013.

- ^ Tippett, Krista (October 25, 2007). "Reinhold Niebuhr Timeline: Opposes Vietnam War". On Being. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Brooks, David (April 26, 2007). "Obama, Gospel and Verse". The New York Times. p. A25. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (December 8, 2020). "Obama, the Best-Selling Author, on Reading, Writing and Radical Empathy". The New York Times. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ "Niebuhr and Obama". Hoover Institution. April 1, 2009. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Christian Realism: A Class Series". Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ Cheever, Susan (March 6, 2012). "The Secret History of the Serenity Prayer". The Fix.

- ^ "Hall of Famous Missourians". Missouri House of Representatives. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "About ADA". Americans for Democratic Action. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Patton, Howard G. "Reinhold Niebuhr". religion-online.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Tippett, Krista (October 25, 2007). "Reinhold Niebuhr Timeline: Accepts Position at Princeton". On Being. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).