| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal Political 16th President of the United States First term Second term Presidential elections Speeches and works

Assassination and legacy  |

||

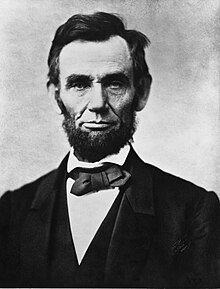

Abraham Lincoln grew up in a highly religious Baptist family. He never joined any Church, and was a skeptic as a young man and sometimes ridiculed revivalists. He frequently referred to God and had a deep knowledge of the Bible, often quoting it. Lincoln attended Protestant church services with his wife and children. "Especially after the death of his young son Willie in 1862, Lincoln moved away from his earlier religious skepticism."[1] Some argue that Lincoln was neither a Christian believer nor a secular freethinker.[2]

Although Lincoln never made an unambiguous public profession of Christian belief, several people who knew him personally, such as Chaplain of the Senate Phineas Gurley and Mary Todd Lincoln, claimed that he believed in Christ in the religious sense.[3][4][5] However, others who had known Lincoln for years, such as Ward Hill Lamon and William Herndon, rejected the idea that he was a believing Christian.[6] During his 1846 run for the House of Representatives, in order to dispel accusations concerning his religious beliefs, Lincoln issued a handbill stating that he had "never denied the truth of the Scriptures".[7] He seemed to believe in an all-powerful God, who shaped events and, by 1865, was expressing those beliefs in major speeches.[8]

- ^ Foner, Eric, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, New York and London: W. W. Norton and Company, 2010, p. 327.

- ^ Gilgoff, Dan (2009-02-12). "Abraham Lincoln's Religious Uncertainty". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

Since his assassination the following month, Christian believers and secular freethinkers have tried to claim him as one of their own. But Lincoln was neither.

- ^ Mary T. Lincoln to James Smith, June 8, 1870, in Robert J. Havlik, "Abraham Lincoln and the Reverend Dr. James Smith: Lincoln's Presbyterian experience of Springfield", Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (Autumn, 1999) online.

- ^ Reed, James A. (July 1873). "The Later Life and Religious Sentiments of Abraham Lincoln". Scribner's Monthly. 6 (3): 339. Quoting Phineas Gurley.

- ^ Reed, James A. (July 1873). "The Later Life and Religious Sentiments of Abraham Lincoln". Scribner's Monthly. 6 (3): 340. Noah Brooks to J. A. Reed, December 31, 1872.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Steiner1936was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Abraham Lincoln Online". Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ Mark A. Noll (1992). A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 321–322. ISBN 9780802806512.