Back Ring van Vuur Afrikaans منطقة الحزام الناري Arabic صمطة لعوافي دلمحيط لمهدن ARY Cinturón de Fueu del Pacíficu AST Bungkung Api Pasifik BAN Singsing nin Kalayo BCL Ціхаакіянскае вогненнае кальцо Byelorussian Тихоокеански огнен пръстен Bulgarian আগুনের বৃত্ত Bengali/Bangla Pacifički vatreni prsten BS

: Earthquakes of magnitude ≥ 7.0 (depth 0–69 km (0–43 mi))

: Earthquakes of magnitude ≥ 7.0 (depth 0–69 km (0–43 mi)) : Active volcanoes

: Active volcanoes

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt)[note 1] is a tectonic belt of volcanoes and earthquakes.

It is about 40,000 km (25,000 mi) long[1] and up to about 500 km (310 mi) wide,[2] and surrounds most of the Pacific Ocean.

The Ring of Fire contains between 750 and 915 active or dormant volcanoes, around two-thirds of the world total.[3][4] The exact number of volcanoes within the Ring of Fire depends on which regions are included.

About 90% of the world's earthquakes,[5] including most of its largest,[6][7] occur within the belt.

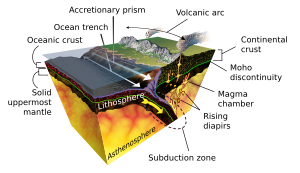

The Ring of Fire is not a single geological structure. It was created by the subduction of different tectonic plates at convergent boundaries around the Pacific Ocean. These include: the Antarctic, Nazca and Cocos plates subducting beneath the South American plate; the Pacific and Juan de Fuca plates beneath the North American plate; the Philippine Plate beneath the Eurasian plate; and a complex boundary between the Pacific and Australian plate. The interactions at these plate boundaries have formed oceanic trenches, volcanic arcs, back-arc basins and volcanic belts.[8] The inclusion of some areas in the Ring of Fire, such as the Antarctic Peninsula and western Indonesia, is disputed.

The Ring of Fire has existed for more than 35 million years[9] but subduction has existed for much longer in some parts of the Ring;[10] many older extinct volcanoes are located within the Ring.[3] More than 350 of the Ring of Fire's volcanoes have been active in historical times,[11][note 2] while the four largest volcanic eruptions on Earth in the Holocene epoch all occurred at volcanoes in the Ring of Fire.[13]

Most of Earth's active volcanoes with summits above sea level are located in the Ring of Fire.[14] Many of these subaerial volcanoes are stratovolcanoes (e.g. Mount St. Helens), formed by explosive eruptions of tephra alternating with effusive eruptions of lava flows. Lavas at the Ring of Fire's stratovolcanoes are mainly andesite and basaltic andesite but dacite, rhyolite, basalt and some other rarer types also occur.[3] Other types of volcano are also found in the Ring of Fire, such as subaerial shield volcanoes (e.g. Plosky Tolbachik), and submarine seamounts (e.g. Monowai).

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "What is the Ring of Fire?". NOAA. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Stern, Robert J.; Bloomer, S. H. (2020). "Subduction zone". Access Science. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.757381.

- ^ a b c Venzke, E, ed. (2013), Volcanoes of the World, v. 4.3.4, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution, doi:10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW4-2013

- ^ Siebert, L; Simkin, T.; Kimberly, P. (2010). Volcanoes of the World (3rd ed.). p. 68.

- ^ "Ring of Fire". United States Geological Survey. July 24, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ "Earthquakes FAQ". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on January 17, 2006.

- ^ "Earthquakes Visual Glossary". United States Geological Survey.

- ^ Wright, John; Rothery, David A. (1998). "The Shape of Ocean Basins". The Ocean Basins: Their Structure and Evolution (2nd ed.). The Open University. pp. 26–53. ISBN 9780080537931.

- ^ Pappas, Stephanie (11 February 2020). "The lost continent of Zealandia hides clues to the Ring of Fire's birth". Live Science.

- ^ Schellart, W. P. (December 2017). "Andean mountain building and magmatic arc migration driven by subduction-induced whole mantle flow". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 2010. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.2010S. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01847-z. PMC 5722900. PMID 29222524.

- ^ Decker, Robert; Decker, Barbara (1981). "The Eruptions of Mount St. Helens". Scientific American. 244 (3): 68–81. Bibcode:1981SciAm.244c..68D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0381-68. JSTOR 24964328.

- ^ Macdonald, G.A. (1972). Volcanoes. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. pp. 346, 430–445. ISBN 9780139422195.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Clive (2011). "Appendix A". Eruptions that Shook the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 355–363. ISBN 978-0-521-64112-8.

- ^ "DESCRIPTION: "Ring of Fire", Plate Tectonics, Sea-Floor Spreading, Subduction Zones, "Hot Spots"". vulcan.wr.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2005-12-31.