Back Sabbatianismus German Ŝabtajanismo (judismo) Esperanto Sabateos Spanish Sabbatéens French שבתאות HE Sabbatizmus Hungarian シャブタイ派 Japanese Sabbatianism NB Sabataizm Polish Саббатианство Russian

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| Jewish mysticism |

|---|

|

| History of Jewish mysticism |

The Sabbateans (or Sabbatians) were a variety of Jewish followers, disciples, and believers in Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676),[1][2][3] an Ottoman Jewish rabbi and Kabbalist who was proclaimed to be the Jewish Messiah in 1666 by Nathan of Gaza.[1][2]

Vast numbers of Jews in the Jewish diaspora accepted his claims, even after he outwardly became an apostate due to his forced conversion to Islam in the same year.[1][2][3] Sabbatai Zevi's followers, both during his proclaimed messiahship and after his forced conversion to Islam, are known as Sabbateans.[1][3]

In the late 17th century, northern Italy experienced a surge of Sabbatean activity, driven by the missionary efforts of Abraham Miguel Cardoso. Around 1700, a radical faction within the Dönmeh movement, led by Baruchiah Russo, emerged, which sought to abolish many biblical prohibitions. During the same period, Sabbatean groups from Poland migrated to the Land of Israel. The Sabbatean movement continued to disseminate throughout central Europe and northern Italy during the 18th century, propelled by "prophets" and "believers." Concurrently, anti-Sabbatean literature emerged, leading to a notable dispute between Rabbi Jacob Emden (Ya'avetz) and Jonathan Eybeschuetz. Additionally, a successor movement known as Frankism, led by Jacob Frank, began in Eastern Europe during this century.[4] Part of the Sabbateans lived on until well into 21st-century Turkey as descendants of the Dönmeh.[1]

- ^ a b c d e

"Judaism - The Lurianic Kabbalah: Shabbetaianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

Rabbi Shabbetai Tzevi of Smyrna (1626–76), who proclaimed himself messiah in 1665. Although the "messiah" was forcibly converted to Islam in 1666 and ended his life in exile 10 years later, he continued to have faithful followers. A sect was thus born and survived, largely thanks to the activity of Nathan of Gaza (c. 1644–90), an unwearying propagandist who justified the actions of Shabbetai Tzevi, including his final apostasy, with theories based on the Lurian doctrine of "repair". Tzevi's actions, according to Nathan, should be understood as the descent of the just into the abyss of the "shells" in order to liberate the captive particles of divine light. The Shabbetaian crisis lasted nearly a century, and some of its aftereffects lasted even longer. It led to the formation of sects whose members were externally converted to Islam—e.g., the Dönmeh (Turkish: "Apostates") of Salonika, whose descendants still live in Turkey—or to Roman Catholicism—e.g., the Polish supporters of Jacob Frank (1726–91), the self-proclaimed messiah and Catholic convert (in Bohemia-Moravia, however, the Frankists outwardly remained Jews). This crisis did not discredit Kabbalah, but it did lead Jewish spiritual authorities to monitor and severely curtail its spread and to use censorship and other acts of repression against anyone—even a person of tested piety and recognized knowledge—who was suspected of Shabbetaian sympathies or messianic pretensions.

- ^ a b c Karp, Abraham J. (2017). ""Witnesses to History": Shabbetai Zvi - False Messiah (Judaic Treasures)". Jewish Virtual Library. American–Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE). Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

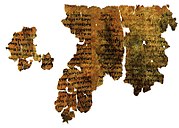

Born in Smyrna in 1626, he showed early promise as a Talmudic scholar, and even more as a student and devotee of Kabbalah. More pronounced than his scholarship were his strange mystical speculations and religious ecstasies. He traveled to various cities, his strong personality and his alternately ascetic and self-indulgent behavior attracting and repelling rabbis and populace alike. He was expelled from Salonica by its rabbis for having staged a wedding service with himself as bridegroom and the Torah as bride. His erratic behavior continued. For long periods, he was a respected student and teacher of Kabbalah; at other times, he was given to messianic fantasies and bizarre acts. At one point, living in Jerusalem seeking "peace for his soul," he sought out a self-proclaimed "man of God," Nathan of Gaza, who declared Shabbetai Zvi to be the Messiah. Then Shabbetai Zvi began to act the part [...] On September 15, 1666, Shabbetai Zvi, brought before the sultan and given the choice of death or apostasy, prudently chose the latter, setting a turban on his head to signify his conversion to Islam, for which he was rewarded with the honorary title "Keeper of the Palace Gates" and a pension of 150 piasters a day. The apostasy shocked the Jewish world. Leaders and followers alike refused to believe it. Many continued to anticipate a second coming, and faith in false messiahs continued through the eighteenth century. In the vast majority of believers revulsion and remorse set in and there was an active endeavor to erase all evidence, even mention of the pseudo messiah. Pages were removed from communal registers, and documents were destroyed. Few copies of the books that celebrated Shabbetai Zvi survived, and those that did have become rarities much sought after by libraries and collectors.

- ^ a b c Kohler, Kaufmann; Malter, Henry (1906). "Shabbetai Ẓevi". Jewish Encyclopedia. Kopelman Foundation. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

At the command [of the sultan], Shabbetai was now taken from Abydos to Adrianople, where the sultan's physician, a former Jew, advised Shabbetai to embrace Islam as the only means of saving his life. Shabbetai realized the danger of his situation and adopted the physician's advice. On the following day [...] being brought before the sultan, he cast off his Jewish garb and put a Turkish turban on his head; and thus his conversion to Islam was accomplished. The sultan was much pleased, and rewarded Shabbetai by conferring on him the title (Mahmed) "Effendi" and appointing him as his doorkeeper with a high salary. [...] To complete his acceptance of Mohammedanism, Shabbetai was ordered to take an additional wife, a Mohammedan slave, which order he obeyed. [...] Meanwhile, Shabbetai secretly continued his plots, playing a double game. At times he would assume the role of a pious Mohammedan and revile Judaism; at others he would enter into relations with Jews as one of their own faith. Thus in March, 1668, he gave out anew that he had been filled with the Holy Spirit at Passover and had received a revelation. He, or one of his followers, published a mystic work addressed to the Jews in which the most fantastic notions were set forth, e.g., that he was the true Redeemer, in spite of his conversion, his object being to bring over thousands of Mohammedans to Judaism. To the sultan he said that his activity among the Jews was to bring them over to Islam. He therefore received permission to associate with his former coreligionists, and even to preach in their synagogues. He thus succeeded in bringing over a number of Mohammedans to his cabalistic views, and, on the other hand, in converting many Jews to Islam, thus forming a Judæo-Turkish sect (see Dönmeh), whose followers implicitly believed in him [as the Jewish Messiah]. This double-dealing with Jews and Mohammedans, however, could not last very long. Gradually the Turks tired of Shabbetai's schemes. He was deprived of his salary, and banished from Adrianople to Constantinople. In a village near the latter city he was one day surprised while singing psalms in a tent with Jews, whereupon the grand vizier ordered his banishment to Dulcigno, a small place in Albania, where he died in loneliness and obscurity.

- ^ Barnavi, Eli, ed. (1992). "The Era of False Messiahs". The Historical Atlas of the Jewish People. Hutchinson. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0-09-177593-0.