Back الاتجار بالجنس Arabic যৌন উদ্দেশ্যে মানব পাচার Bengali/Bangla Sex trafficking German Tráfico sexual Spanish قاچاق جنسی Persian Trafic sexuel French סחר בבני אדם למטרות מין HE Սեռական թրաֆիքինգ Armenian Perdagangan seks ID Ajhuwâlân jima' MAD

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (July 2020) |

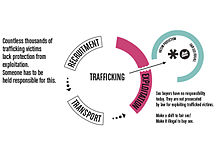

Sex trafficking is human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Perpetrators of the crime are called sex traffickers or pimps—people who manipulate victims to engage in various forms of commercial sex with paying customers. Sex traffickers use force, fraud, and coercion as they recruit, transport, and provide their victims as prostitutes.[1] Sometimes victims are brought into a situation of dependency on their trafficker(s), financially or emotionally.[2] Every aspect of sex trafficking is considered a crime, from acquisition to transportation and exploitation of victims.[3] This includes any sexual exploitation of adults or minors, including child sex tourism (CST) and domestic minor sex trafficking (DMST).[2] It has been called a form of modern slavery because of the way victims are forced into sexual acts non-consensually, in a form of sexual slavery.[3]

In 2012, the International Labour Organization (ILO) reported 20.9 million people were subjected to forced labor, and 22% (4.5 million) were victims of forced sexual exploitation, 300,000 of them in Developed Economies and the EU.[4] The ILO reported in 2016 that of the estimated 25 million persons in forced labor, 5 million were victims of sexual exploitation.[5][6] However, due to the covertness of sex trafficking, obtaining accurate, reliable statistics poses a challenge for researchers.[7] The global commercial profits for sexual slavery are estimated to be $99 billion, according to ILO.[8] In 2005, the figure was given as $9 billion for the total human trafficking.[9][10]

Sex trafficking typically occurs in situations from which escape is both difficult and dangerous. Networks of traffickers exist in every country. Therefore, victims are often trafficked across state and country lines which causes jurisdictional concerns and make cases difficult to prosecute.[11]

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Human Trafficking". www.acf.hhs.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Global Social Welfarewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Elrod, John (April 2015). "Filling the gap: refining sex trafficking legislation to address the problem of pimping". Vanderbilt Law Review. 68: 961 – via Hein Online.

- ^ "ILO 2012 Global estimate of forced labour – Executive summary" (PDF). International Labour Organization. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Odhiambo, Agnes & Barr, Heather. (2 Aug 2019). "Opinion:Trafficking survivors are being failed the world over." Al Jazeera website Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ International Labour Organization. (19 September 2017). Press Release:40 million in modern slavery and 152 million in child labour around the world. International Labour Organization website Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Tiefenbrunwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Human Trafficking by the Numbers". (7 January 2017). Human Rights First website Archived 7 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Daffron, Joshua W. (Dec 2011). "Combating Human Trafficking: Evolution of State Legislation and the Policies of the United Kingdom and France." Thesis, M.A. Monterey, Calif.:Department of National Security Affairs. Naval Postgraduate School. Defense Technical Information Center website Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Tiziana Luise. (2005). "Are human rights becoming burdensome for our economies? The role of slavery-like practices in the development of world economics and in the context of modern society," Rivista Internazionale Di Scienze Sociali, 113(3): 473.

- ^ "Why is Human Trafficking So Difficult to Stop?". Kinship United. Retrieved 10 December 2022.