Back الأناجيل الإزائية Arabic الاناجيل السينوبتيكيه ARZ Сінаптычныя Евангеллі Byelorussian Сынаптычныя Эвангельлі BE-X-OLD Синоптични евангелия Bulgarian Evangelis sinòptics Catalan ئینجیلی سینۆپتی CKB Synoptické evangelium Czech Synoptiske evangelier Danish Synoptische Evangelien German

| Part of a series on the |

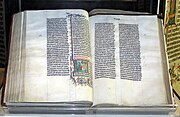

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are referred to as the synoptic Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical wording. They stand in contrast to John, whose content is largely distinct. The term synoptic (Latin: synopticus; Greek: συνοπτικός, romanized: synoptikós) comes via Latin from the Greek σύνοψις, synopsis, i.e. "(a) seeing all together, synopsis".[n 1] The modern sense of the word in English is of "giving an account of the events from the same point of view or under the same general aspect".[2] It is in this sense that it is applied to the synoptic gospels.

This strong parallelism among the three gospels in content, arrangement, and specific language is widely attributed to literary interdependence,[3] though the role of orality and memorization of sources has also been explored by scholars.[4][5] The question of the precise nature of their literary relationship—the synoptic problem—has been a topic of debate for centuries and has been described as "the most fascinating literary enigma of all time".[6] While no conclusive solution has been found yet, the longstanding majority view favors Marcan priority, in which both Matthew and Luke have made direct use of the Gospel of Mark as a source, and further holds that Matthew and Luke also drew from an additional hypothetical document, called Q.[7]

- ^ Honoré, A. M. (1968). "A Statistical Study of the Synoptic Problem". Novum Testamentum. 10 (2/3): 95–147. doi:10.2307/1560364. ISSN 0048-1009. JSTOR 1560364.

- ^ a b "synoptic". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) Harper, Douglas. "synoptic". Online Etymology Dictionary. Harper, Douglas. "synopsis". Online Etymology Dictionary. Harper, Douglas. "optic". Online Etymology Dictionary. σύν, ὄπτός, ὀπτικός, ὄψις, συνοπτικός, σύνοψις. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Goodacre, Mark (2001). The Synoptic Problem: A Way Through the Maze. A&C Black. p. 16. ISBN 0567080560.

- ^ Derico, Travis (2018). Oral Tradition and Synoptic Verbal Agreement: Evaluating the Empirical Evidence for Literary Dependence. Pickwick Publications, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-1620320907.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2019). Q in Matthew: Ancient Media, Memory, and Early Scribal Transmission of the Jesus Tradition. T&T Clark. pp. 148–183. ISBN 978-0567686541.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), p. 32.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 20–21.

Cite error: There are <ref group=n> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=n}} template (see the help page).