Back معاهدة وايتانغي Arabic معاهدة وايطانݣي ARY Tratáu de Waitangi AST Vaytanq müqaviləsi Azerbaijani Пагадненне Вайтангі Byelorussian Пагадненьне Вайтангі BE-X-OLD Tractat de Waitangi Catalan Smlouva z Waitangi Czech Cytundeb Waitangi Welsh Vertrag von Waitangi German

This article's lead section may be too long. (November 2024) |

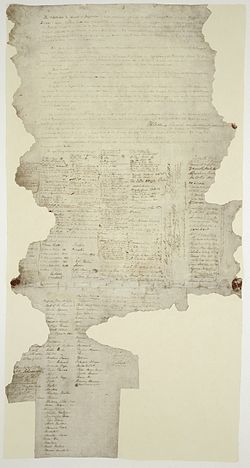

The Waitangi Sheet of the Treaty of Waitangi | |

| Context | Treaty to establish a British Governor of New Zealand, consider Māori ownership of their lands and other properties, and give Māori the rights of British subjects |

|---|---|

| Drafted | 4–5 February 1840 by William Hobson with the help of his secretary, James Freeman, and British Resident James Busby |

| Signed | 6 February 1840 |

| Location | Waitangi in the Bay of Islands, and various other locations in New Zealand. Currently held at National Library of New Zealand, Wellington. |

| Signatories | Representatives of the British Crown, various Māori chiefs from the northern North Island, and later a further 500 signatories |

| Languages | English, Māori |

| Full text | |

| www | |

| History of New Zealand |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| General topics |

| Prior to 1800 |

| 19th century |

| Stages of independence |

| World Wars |

| Post-war and contemporary history |

|

| See also |

|

|

The Treaty of Waitangi (Māori: Te Tiriti o Waitangi), sometimes referred to as Te Tiriti, is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the treatment of the Māori people in New Zealand by successive governments and the wider population, something that has been especially prominent from the late 20th century. The treaty document is an agreement, not a treaty as recognised in international law.[1] It was first signed on 6 February 1840 by Captain William Hobson as consul for the British Crown and by Māori chiefs (rangatira) from the North Island of New Zealand. The treaty's quasi-legal status satisfies the demands of biculturalism in contemporary New Zealand society. In general terms, it is interpreted today as having established a partnership between equals in a way the Crown likely did not intend it to in 1840. Specifically, the treaty is seen, first, as entitling Māori to enjoyment of land and of natural resources and, if that right were ever breached, to restitution. Second, the treaty's quasi-legal status has clouded the question of whether Māori had ceded sovereignty to the Crown in 1840, and if so, whether such sovereignty remains intact.[2]

The treaty was written at a time when the New Zealand Company, acting on behalf of large numbers of settlers and would-be settlers, was establishing a colony in New Zealand, and when some Māori leaders had petitioned the British for protection against French ambitions. It was drafted with the intention of establishing a British Governor of New Zealand, recognising Māori ownership of their lands, forests and other possessions, and giving Māori the rights of British subjects. It was intended by the British Crown to ensure that when Lieutenant Governor Hobson subsequently made the declaration of British sovereignty over New Zealand in May 1840, the Māori people would not feel that their rights had been ignored.[3] Once it had been written and translated, it was first signed by Northern Māori leaders at Waitangi. Copies were subsequently taken around New Zealand and over the following months many other chiefs signed.[4] Around 530 to 540 Māori, at least 13 of them women, signed the Māori language version of the Treaty of Waitangi, despite some Māori leaders cautioning against it.[5][6] Only 39 signed the English version.[7] An immediate result of the treaty was that Queen Victoria's government gained the sole right to purchase land.[8] In total there are nine signed copies of the Treaty of Waitangi, including the sheet signed on 6 February 1840 at Waitangi.[9]

The text of the treaty includes a preamble and three articles. It is bilingual, with the Māori text translated in the context of the time from the English.

- Article one of the Māori text grants governance rights to the Crown while the English text cedes "all rights and powers of sovereignty" to the Crown.

- Article two of the Māori text establishes that Māori will retain full chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures while the English text establishes the continued ownership of the Māori over their lands and establishes the exclusive right of pre-emption of the Crown.

- Article three gives Māori people full rights and protections as British subjects.

As some words in the English treaty did not translate directly into the written Māori language of the time, the Māori text is not an exact translation of the English text, particularly in relation to the meaning of having and ceding sovereignty.[10][11] These differences created disagreements in the decades following the signing, eventually contributing to the New Zealand Wars of 1845 to 1872 and continuing through to the Treaty of Waitangi settlements starting in the early 1990s.

During the second half of the 19th century Māori generally lost control of much of the land they had owned, sometimes through legitimate sale, but often by way of unfair deals, settlers occupying land that had not been sold, or through outright confiscations in the aftermath of the New Zealand Wars. In the period following the New Zealand Wars, the New Zealand government mostly ignored the treaty, and a court judgement in 1877 declared it to be "a simple nullity". Beginning in the 1950s, Māori increasingly sought to use the treaty as a platform for claiming additional rights to sovereignty and to reclaim lost land, and governments in the 1960s and 1970s responded to these arguments, giving the treaty an increasingly central role in the interpretation of land rights and relations between Māori people and the state.

In 1975 the New Zealand Parliament passed the Treaty of Waitangi Act, establishing the Waitangi Tribunal as a permanent commission of inquiry tasked with interpreting the treaty, investigating breaches of the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi by the Crown or its agents, and suggesting means of redress.[10] In most cases, recommendations of the tribunal are not binding on the Crown, but settlements with a total value of roughly $1 billion have been awarded to various Māori groups.[10][12] Various legislation passed in the latter part of the 20th century has made reference to the treaty, which has led to ad hoc incorporation of the treaty into law.[13] Increasingly, the treaty is recognised as a founding document in New Zealand's developing unwritten constitution.[14][15][16] The New Zealand Day Act 1973 established Waitangi Day as a national holiday to commemorate the signing of the treaty.

- ^ Cox, Noel (2002). "The Treaty of Waitangi and the Relationship Between the Crown and Maori in New Zealand". Brooklyn Journal of International Law. 28 (1): 132. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Kolig, Erich (2000). "Of Condoms, Biculturalism, and Political Correctness. The Maori Renaissance and Cultural Politics in New Zealand". Paideuma. 46. JSTOR: 238. JSTOR 40341791.

- ^ "Additional Instructions from Lord Normanby to Captain Hobson 1839 – New Zealand Constitutional Law Resources". New Zealand Legal Information Institute. 15 August 1839. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi signings in the South Island". Christchurch City Libraries. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi". Waitangi Tribunal. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Orange 1987, p. 260.

- ^ Newman, Keith (2010) [2010]. Bible & Treaty, Missionaries among the Māori – a new perspective. Google Books: Penguin. ISBN 978-0143204084. pp 159

- ^ Burns, Patricia (1989). Fatal Success: A History of the New Zealand Company. Heinemann Reed. ISBN 0-7900-0011-3.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi – Te Tiriti o Waitangi". Archives New Zealand. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b c "Meaning of the Treaty". Waitangi Tribunal. 2011. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Newman, Keith (2010) [2010]. Bible & Treaty, Missionaries among the Māori – a new perspective. Penguin. ISBN 978-0143204084. pp 20-116

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Settlementswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Palmer 2008, p. 292.

- ^ "New Zealand's Constitution". Government House. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "New Zealand's constitution – past, present and future" (PDF). Cabinet Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 24.