Back الأزمة الفنزويلية 1895 Arabic Venezuelan kriisi Finnish Crise vénézuélienne de 1895 French Crisi venezuelana del 1895 Italian Crise da Venezuela de 1895 Portuguese Венесуэльский кризис (1895) Russian Venezuelanska kriza (1895) Serbo-Croatian Венесуельська криза Ukrainian 1895年委内瑞拉危机 Chinese

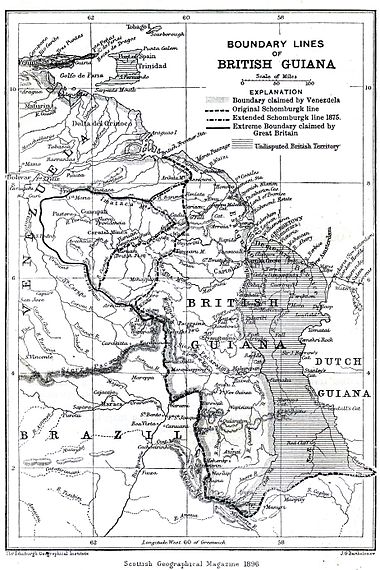

* The extreme border claimed by Britain

* The current boundary (roughly) and

* The extreme border claimed by Venezuela

| Guyana–Venezuela territorial dispute |

|---|

|

| History |

|

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895[a] occurred over Venezuela's longstanding dispute with Great Britain about the territory of Essequibo, which Britain believed was part of British Guiana and Venezuela recognized as its own Guayana Esequiba. The issue became more acute with the development of gold mining in the region.

As the dispute became a crisis, the key issue became Britain's refusal to include in the proposed international arbitration the territory east of the "Schomburgk Line", which a surveyor had drawn half-a-century earlier as a boundary between Venezuela and the former Dutch territory ceded by the Dutch in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, later part of British Guiana.[1] The crisis ultimately saw Britain accept the United States' intervention in the dispute to force arbitration of the entire disputed territory, and tacitly accept the US right to intervene under the Monroe Doctrine. A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[2]

The dispute had become a diplomatic crisis in 1895 when a lobbyist for Venezuela William Lindsay Scruggs sought to argue that British behaviour over the issue violated the 1823 Monroe Doctrine and used his influence in Washington, DC, to pursue the matter. US President Grover Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Doctrine that forbade new European colonies but also declared an American interest in any matter in the hemisphere.[3] British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and the British ambassador to Washington, Julian Pauncefote, misjudged the importance the American government placed on the dispute, prolonging the crisis before ultimately accepting the American demand for arbitration[4][5] of the entire territory.

By standing with a Latin American nation against European colonial powers, Cleveland improved relations with the United States' southern neighbors, but the cordial manner in which the negotiations were conducted also made for good relations with Britain.[6] However, by backing down in the face of a strong US declaration of a strong interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, Britain tacitly accepted it, and the crisis thus provided a basis for the expansion of US interventionism in the Americas.[7] Leading British historian Robert Arthur Humphreys later called the crisis "one of the most momentous episodes in the history of Anglo-American relations in general and of Anglo-American rivalries in Latin America in particular."

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ King (2007:249)

- ^ Graff, Henry F., Grover Cleveland (2002). ISBN 0-8050-6923-2. pp123-25

- ^ Zakaria, Fareed, From Wealth to Power (1999). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01035-8. pp145–146

- ^ Paul Gibb, "Unmasterly Inactivity? Sir Julian Pauncefote, Lord Salisbury, and the Venezuela Boundary Dispute," Diplomacy and Statecraft, Mar 2005, Vol. 16 Issue 1, pp 23–55

- ^ Nelson M. Blake, "Background of Cleveland's Venezuelan Policy," American Historical Review, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Jan., 1942), pp. 259–277 in JSTOR

- ^ Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage (1932). ASIN B000PUX6KQ., 550, 633–648

- ^ Historian George Herring wrote that by failing to pursue the issue further the British "tacitly conceded the U. S. definition of the Monroe Doctrine and its hegemony in the hemisphere." Herring, George C., From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776, (2008) pp. 307–308