Back ندرة المياه Arabic Su qıtlığı Azerbaijani পানি ঘাটতি Bengali/Bangla Escassetat d'aigua Catalan کێشەی کەمئاوی CKB Wasserknappheit German Λειψυδρία Greek Akvomalabundo Esperanto Escasez de agua Spanish کمبود آب Persian

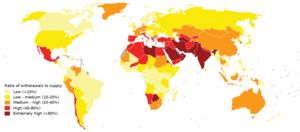

Water scarcity (closely related to water stress or water crisis) is the lack of fresh water resources to meet the standard water demand. There are two types of water scarcity. One is physical. The other is economic water scarcity.[2]: 560 Physical water scarcity is where there is not enough water to meet all demands. This includes water needed for ecosystems to function. Regions with a desert climate often face physical water scarcity.[3] Central Asia, West Asia, and North Africa are examples of arid areas. Economic water scarcity results from a lack of investment in infrastructure or technology to draw water from rivers, aquifers, or other water sources. It also results from weak human capacity to meet water demand.[2]: 560 Many people in Sub-Saharan Africa are living with economic water scarcity.[4]: 11

There is enough freshwater available globally and averaged over the year to meet demand. As such, water scarcity is caused by a mismatch between when and where people need water, and when and where it is available.[5] This can happen due to an increase in the number of people in a region, changing living conditions and diets, and expansion of irrigated agriculture.[6][7][8] Climate change (including droughts or floods), deforestation, water pollution and wasteful use of water can also mean there is not enough water.[9] These variations in scarcity may also be a function of prevailing economic policy and planning approaches.

Water scarcity assessments look at many types of information. They include green water (soil moisture), water quality, environmental flow requirements, and virtual water trade.[8] Water stress is one parameter to measure water scarcity. It is useful in the context of Sustainable Development Goal 6.[10] Half a billion people live in areas with severe water scarcity throughout the year,[5][8] and around four billion people face severe water scarcity at least one month per year.[5][11] Half of the world's largest cities experience water scarcity.[11] There are 2.3 billion people who reside in nations with water scarcities (meaning less than 1700 m3 of water per person per year).[12][13][14]

There are different ways to reduce water scarcity. It can be done through supply and demand side management, cooperation between countries and water conservation. Expanding sources of usable water can help. Reusing wastewater and desalination are ways to do this. Others are reducing water pollution and changes to the virtual water trade.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:15was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Caretta, M.A., A. Mukherji, M. Arfanuzzaman, R.A. Betts, A. Gelfan, Y. Hirabayashi, T.K. Lissner, J. Liu, E. Lopez Gunn, R. Morgan, S. Mwanga, and S. Supratid, 2022: Chapter 4: Water. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 551–712, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.006.

- ^ Rijsberman, Frank R. (2006). "Water scarcity: Fact or fiction?". Agricultural Water Management. 80 (1–3): 5–22. Bibcode:2006AgWM...80....5R. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2005.07.001.

- ^ IWMI (2007) Water for Food, Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. London: Earthscan, and Colombo: International Water Management Institute.

- ^ a b c Mekonnen, Mesfin M.; Hoekstra, Arjen Y. (2016). "Four billion people facing severe water scarcity". Science Advances. 2 (2): e1500323. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E0323M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500323. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4758739. PMID 26933676.

- ^ Vorosmarty, C. J. (14 July 2000). "Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth". Science. 289 (5477): 284–288. Bibcode:2000Sci...289..284V. doi:10.1126/science.289.5477.284. PMID 10894773. S2CID 37062764.

- ^ Ercin, A. Ertug; Hoekstra, Arjen Y. (2014). "Water footprint scenarios for 2050: A global analysis". Environment International. 64: 71–82. Bibcode:2014EnInt..64...71E. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2013.11.019. PMID 24374780.

- ^ a b c Liu, Junguo; Yang, Hong; Gosling, Simon N.; Kummu, Matti; Flörke, Martina; Pfister, Stephan; Hanasaki, Naota; Wada, Yoshihide; Zhang, Xinxin; Zheng, Chunmiao; Alcamo, Joseph (2017). "Water scarcity assessments in the past, present, and future: Review on Water Scarcity Assessment". Earth's Future. 5 (6): 545–559. doi:10.1002/2016EF000518. PMC 6204262. PMID 30377623.

- ^ "Water Scarcity. Threats". WWF. 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:172was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "How do we prevent today's water crisis becoming tomorrow's catastrophe?". World Economic Forum. 23 March 2017. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Wastewater resource recovery can fix water insecurity and cut carbon emissions". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "International Decade for Action 'Water for Life' 2005-2015. Focus Areas: Water scarcity". www.un.org. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "THE STATE OF THE WORLD'S LAND AND WATER RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE" (PDF).