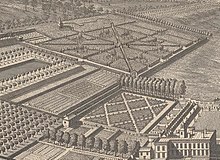

In the Western history of gardening, from the 16th to early 19th centuries, a wilderness was a highly artificial and formalized type of woodland, forming a section of a large garden.[1] Though examples varied greatly, a typical English style was a number of geometrically-arranged compartments (often called "quarters") closed round by hedges, each compartment planted inside with relatively small trees. Between the compartments there were wide walkways or "alleys", usually of grass, sometimes of gravel. The wilderness provided shade in hot weather, and relative privacy. Though often said by garden writers at the time to be intended for meditation and reading, the wilderness was much used for walking, and often flirtation. There were few if any flowers, but there might be statues, and some seating, especially in garden rooms or salle vertes ("green rooms"), clearings left empty. Some had other features, such as a garden maze.[1]

The wilderness was planted close, but not too close, to the main house, often beyond the parterres, or at an oblique angle to the garden front; garden critics often complained they were too close or too far.[2] If there was a far-reaching view from the house, the wilderness was not supposed to obstruct it,[3] but if the garden adjoined buildings, obstruction of the view to these might be an advantage. Generally the garden front of the house opened to a terrace followed by an area set out in parterres, often including "plats" of plain grass. Wilderness areas would be beyond or beside this.[4]

The wilderness broadly equates to one type of the French bosquet, and that term was sometimes used in English at the time; the rather vague term "grove" is also often used, for these but sometimes apparently for any group of trees, regardless of their height or formal placing.[6] But the French examples were more likely to plant the trees in a regular pattern, and using the same species. In particular the French bosquet may consist only of trees set out in lines, and not have hedges around the groups of trees; this type is still very common in urban squares in France. The full French formal garden was likely to include bosquets with hedges, which in continental examples were often higher than was usual in England, shown in depictions dwarfing walkers in the garden, as those in the gardens of Versailles still do. The trees were usually deciduous, giving shade in summer, and letting in more light in winter.[7]

The wilderness fell from fashion with the rise in the 18th century of the English landscape garden, and specifically the new form of the shrubbery.[8] In the 19th century, with the Romantic movement and an increasing number of garden plants new to Europe, a new type of much more natural woodland garden emerged, combining a more or less natural woodland setting with choice specimens of shrubs, flowers and trees.[9] Most wildernesses were turned into these other types of garden, or gradually reverted to woodland as the trees grew.[10] There have been some reinstatements in recent years, as at Ham House, near London.[11]

- ^ a b HEALD, "Wilderness"; Woudstra, 3–11; Eburne and Taylor, 88–89; Clark:1

- ^ For example Batty Langley, quoted in HEALD, "Wilderness", "Citations", and other comments on placing wildernesses

- ^ See for example Philip Miller, quoted in HEALD, "Wilderness", "Citations"

- ^ Hunt, 161–164

- ^ Jacques, 141

- ^ HEALD, "Wilderness", and also "Grove", "Clump"; Woudstra, 1–6

- ^ HEALD, "Wilderness"; Woudstra, 7, 10; Clark:1

- ^ Woudstra, 9, 11; Eburne and Taylor, 89

- ^ HEALD, "Wilderness"

- ^ Williamson, 8–9

- ^ Eburne and Taylor, 88

- ^ Woudstra, 10; Jacques, 213