Back علم فلك الأشعة السينية Arabic Rentgen astronomiya Azerbaijani Astronomia de raigs X Catalan Rentgenová astronomie Czech Röntgenastronomie German Αστρονομία ακτίνων Χ Greek Astronomía de rayos-X Spanish Röntgenastronoomia Estonian اخترشناسی پرتو ایکس Persian Röntgentähtitiede Finnish

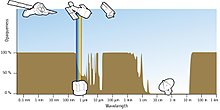

X-ray astronomy is an observational branch of astronomy which deals with the study of X-ray observation and detection from astronomical objects. X-radiation is absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, so instruments to detect X-rays must be taken to high altitude by balloons, sounding rockets, and satellites. X-ray astronomy uses a type of space telescope that can see x-ray radiation which standard optical telescopes, such as the Mauna Kea Observatories, cannot.

X-ray emission is expected from astronomical objects that contain extremely hot gases at temperatures from about a million kelvin (K) to hundreds of millions of kelvin (MK). Moreover, the maintenance of the E-layer of ionized gas high in the Earth's thermosphere also suggested a strong extraterrestrial source of X-rays. Although theory predicted that the Sun and the stars would be prominent X-ray sources, there was no way to verify this because Earth's atmosphere blocks most extraterrestrial X-rays. It was not until ways of sending instrument packages to high altitudes were developed that these X-ray sources could be studied.

The existence of solar X-rays was confirmed early in the mid-twentieth century by V-2s converted to sounding rockets, and the detection of extra-terrestrial X-rays has been the primary or secondary mission of multiple satellites since 1958.[1] The first cosmic (beyond the Solar System) X-ray source was discovered by a sounding rocket in 1962. Called Scorpius X-1 (Sco X-1) (the first X-ray source found in the constellation Scorpius), the X-ray emission of Scorpius X-1 is 10,000 times greater than its visual emission, whereas that of the Sun is about a million times less. In addition, the energy output in X-rays is 100,000 times greater than the total emission of the Sun in all wavelengths.

Many thousands of X-ray sources have since been discovered. In addition, the intergalactic space in galaxy clusters is filled with a hot, but very dilute gas at a temperature between 100 and 1000 megakelvins (MK). The total amount of hot gas is five to ten times the total mass in the visible galaxies.

- ^ Significant Achievements in Solar Physics 1958-1964. Washington D.C.: NASA. 1966. pp. 49–58.